Share this article

Wild Cam: The strength and limitations of community science

How good are you at spotting a giraffe?

While the world’s tallest land animals might seem difficult to miss, community scientists commonly fail to see and identify the yellow-spotted ungulates in trail camera images.

“We were able to recover hundreds of images of giraffes that went unclassified by citizen scientists because the animals were too far in the distance and very difficult to see,” said Nicole Egna, a master’s student at Duke University.

San Diego Zoo Global created a community science project called Wildwatch Kenya, in which volunteers from the general public sort through thousands trail camera images taken from 2016 to 2020. Anybody interested could help to spot animals in pictures and identify the species on Zooniverse, a website that creates a platform for community science projects like this.

Enlarge

Credit: Wildwatch Kenya

Egna, who worked with the San Diego Zoo Global’s Institute for Conservation Research at the time of the research, and her colleagues wanted to see how accurate volunteers were at finding wildlife and properly identifying species in both the Wildwatch Kenya project and the similar Snapshot Serengeti project. In both projects, community scientists do the bulk of the work, going through millions of photos with and without wildlife, while experts step in to confirm identified wildlife and sort out difficult identifications.

In a study published recently in Ecology and Evolution, the researchers found that overall, community scientists were 83.4% accurate in the Wildwatch Kenya project.

But their research also revealed some trends when it came to people’s inaccurate identifications. Wildwatch Kenya, for example, was less accurate overall than Snapshot Serengeti, which was 97.9% accurate. Egna said this is likely due to differences in the setup of the cameras.

Enlarge

Credit: Wildwatch Kenya

In Wildwatch, trail cameras were set to take single shots when detecting movement, while cameras that were part of Snapshot Serengeti took bursts of three shots when detecting movement. On the website, volunteers could click through the bursts to see the small changes in movement, detecting moving animals more easily on an otherwise static landscape. When presented with a single image, it was harder to see distant species.

In both projects, Egna said that it was more common for community scientists to miss animals altogether rather than to misidentify a species that was present.

“There were very few false species images, whereas there were many false empty images,” Egna said.

Enlarge

Credit: Wildwatch Kenya

This distinction likely has to do with the setup of both projects. When someone identifies any animal, other volunteers will see it and add their input, often correcting any initial mistakes. The setup of the projects also meant that more people were seeing images that were tagged as having wildlife than ones that were marked as empty.

Many community scientists also misidentified images as empty because they missed animals that were far in the distance. Moving grass in the foreground would sometimes trigger the motion sensors on cameras. Community scientists often marked them as empty, perhaps believing the grass set the cameras off. But sometimes, even if it was the grass that set the camera off, there were still animals in the background that happened to be there. People often missed those animals in the distance.

Enlarge

Credit: Wildwatch Kenya

This problem is partly why giraffes were so often missed, despite being so tall. Unlike shorter animals like lions or hyenas, giraffes in the far distance can be seen by experts, but are easily missed to the untrained eye, or to people not seeing images of the same landscape in sequence.

“At that distance, even an expert wouldn’t see a lion. It’s only because giraffes are so big that we were able to see them,” Egna said.

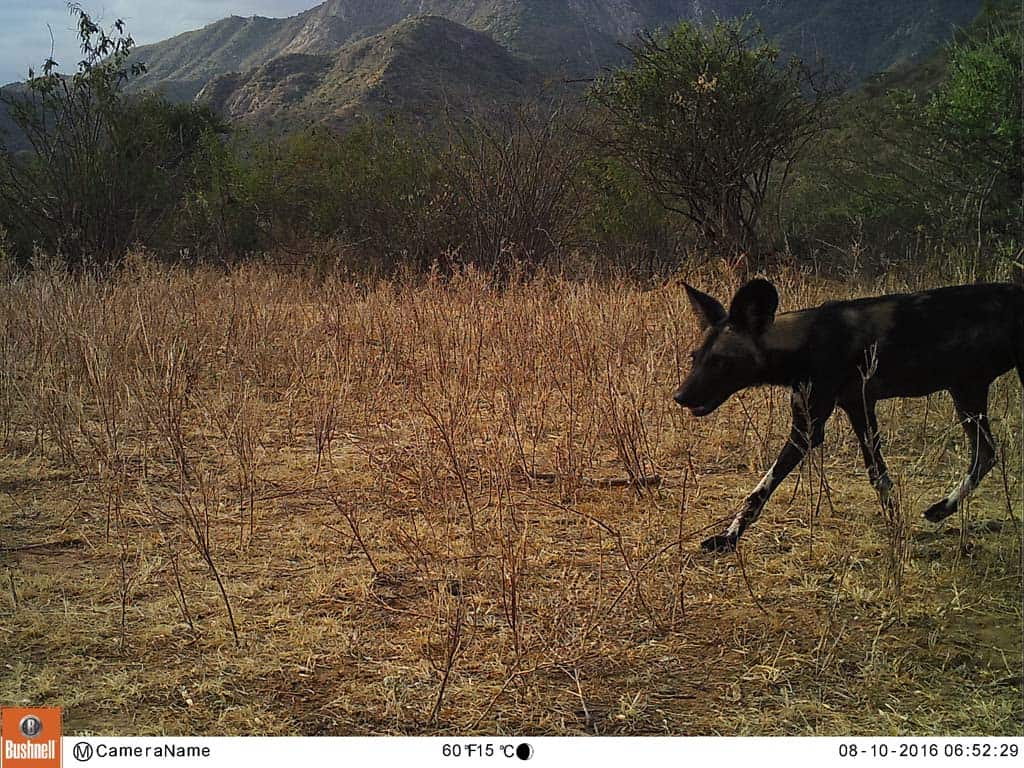

Enlarge

Credit: Wildwatch Kenya

But there were still some misidentified animals, such as the one in the shot above. Users believed the animals above were impala (Aepyceros melampus), when in reality they were gazelles (Gazella Spp.). But these mistakes were few and far between.

“When they recognize that there is a species in the image, they are usually very good at determining what that species is,” Egna said about community scientists.

Enlarge

Credit: Wildwatch Kenya

Some of the problems that made Wildwatch less accurate than Snapshot Serengeti, she said, had to do with the set-up of the trail cameras. Unless researchers post bursts of images like Snapshot Serengeti did, the program organizes images randomly rather than showing multiple shots in a row from the same camera. Zooniverse presents images in random order to reduce fatigue associated with classifying many images with the same landscape.

But retaining a mostly randomized order that still shows images in short series from the same camera might improve users’ ability to notice hard-to-see wildlife. Egna said that the researchers have shared the results of their study with Zooniverse.

Enlarge

Credit: Wildwatch Kenya

This photo essay is part of an occasional series from The Wildlife Society featuring photos and video images of wildlife taken with camera traps and other equipment. Check out other entries in the series here. If you’re working on an interesting camera trap research project or one that has a series of good photos you’d like to share, email Joshua at jlearn@wildlife.org.

Header Image: Elephants pass by a trail camera in Kenya. Credit: Wildwatch Kenya