Share this article

JWM: Big cats adapt to city life

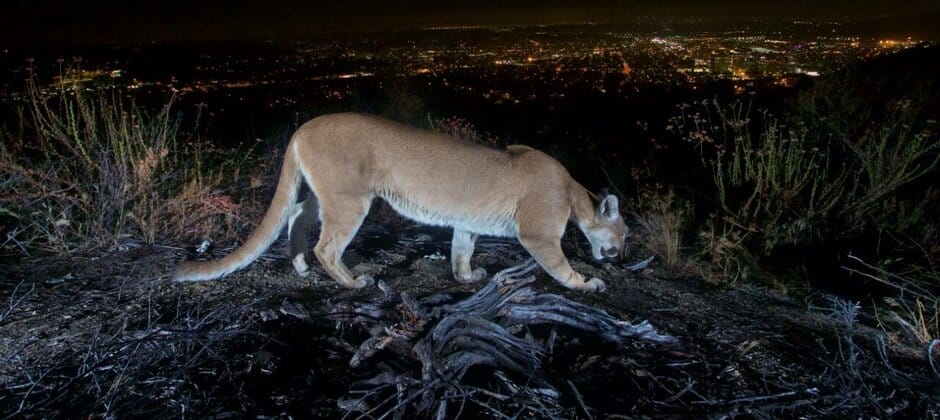

Mountain lions live closer to developed areas in Los Angeles than researchers previously thought.

Los Angeles, one of the largest metropolitan areas in the country, is home to about 18 million people. But mountain lions, which are sensitive to landscapes altered by humans, also roam close to the city.

“Historically, we think of large carnivores as creatures of the wilderness,” said John Benson, an assistant professor of vertebrate ecology at the University of Nebraska and co-author of a recent mountain lion study published in The Journal of Wildlife Management. “However, we should conserve them in areas that are shared by humans, as well.”

In the study, lead author Seth Riley, a wildlife ecologist and branch chief for wildlife at the National Park Service, and his team fit mountain lions (Puma concolor) with GPS collars to determine where they’re spending their time in Los Angeles.

The researchers collected data on the mountain lions’ home range size and the land they were using in the Santa Monica Mountains and surrounding areas from 2002 to 2016.

They also looked at how pumas responded to development and open areas modified by humans like cemeteries and golf courses versus undeveloped habitats like dense shrubs and other natural vegetation. “This is the largest metropolitan area occupied by large carnivores in the United States,” Benson said.

The team discovered that mountain lions selected areas closer to human development more than expected by chance. They think that’s because of the presence of mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) and other prey in areas closer to urbanization.

GPS data also showed mountain lions adapted to human-dominated landscapes. For example, two mountain lions living in the most heavily impacted area showed how the species, which are usually active at sunrise and sunset, adapted their behavior to avoid humans. They became more active at night when humans were least active.

Still, the “results show that developed and highly modified landscapes don’t benefit mountain lions,” Riley said. Mountain lions in urbanized areas had larger home ranges because they need to travel larger distances and use more space to avoid human activity.

On the other hand, the two mountain lions that lived in the most urban portion of the study area had the smallest home range sizes ever reported for male mountain lions. Their habitat is surrounded by large freeways and dense neighborhoods. Usually, males have large ranges to overlap with multiple females. The restrictions of urbanization and busy roads prevented these two males from being in close proximity to mates.

Mountain lions also rarely entered developed areas and consistently avoided open spaces like golf courses and cemeteries. “Mountain lions tend to select areas with dense cover, which they use for stalking and ambushing prey,” Benson said.

Another key finding is the importance of chaparral vegetation as dense cover for mountain lions. “Chaparral and shrubs weren’t widely recognized as an important feature of mountain lion habitat prior to this study,” Benson said. He suggests conserving these plant communities in Los Angeles for aiding puma preservation.

Overall, despite their proximity to human development, the team found mountain lions keenly avoided areas dominated by humans. “Their survival is a testament to the amount of natural area that still exists in southern California, but significant challenges remain,” Riley said.

This article features research that was published in a TWS peer-reviewed journal. Individual online access to all TWS journal articles is a benefit of membership. Join TWS now to read the latest in wildlife research.

Header Image: Mountain lions are adapting to human-dominated landscapes in Los Angeles. Credit: NPS Photo