Share this article

Deer makes epic trip across Missouri

The three-year old buck known as N17003 started its trip like many other white-tailed deer in the beginning of November, 2017. Researchers from the University of Missouri and Missouri Department of Conservation had captured the white-tailed deer, at the beginning of that year, and fitted it with a GPS collar, along with about 700 others, in two major areas of the state — one in the north, and one in the south.

The buck hung around a rural area north of Kansas City for about 11 months. Every five hours, its collar sent location data to researchers.

But by November, the deer set out on what would become an epic journey of the longest white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) movement that researchers have ever tracked.

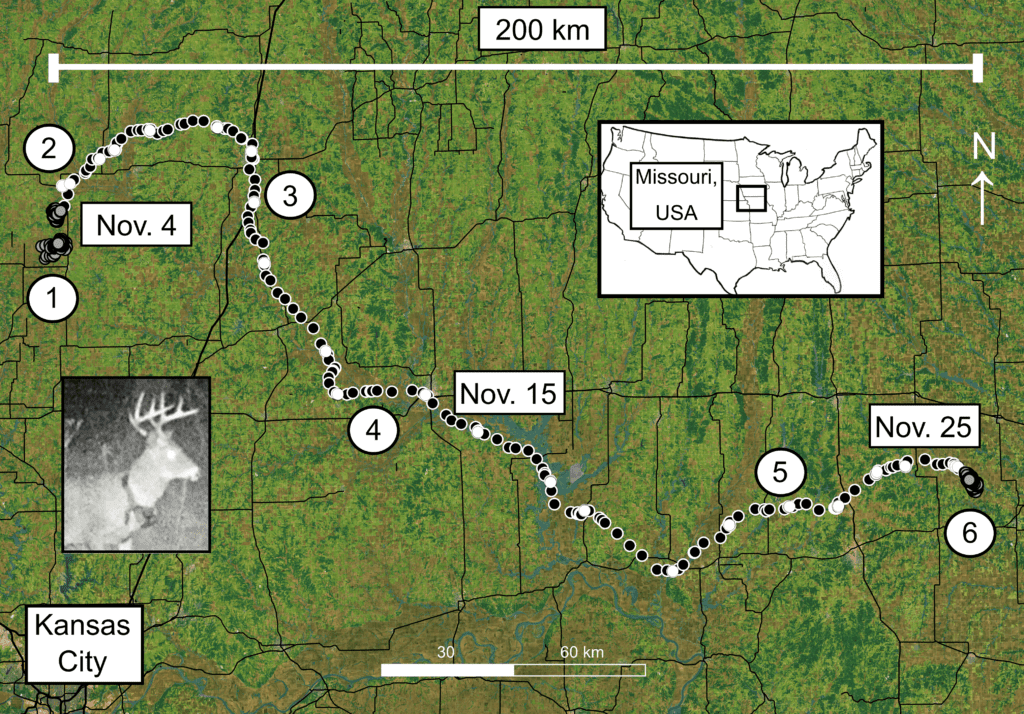

A map shows the dispersal of a white-tailed deer across Missouri.

Credit: Missouri Department of Conservation

“This was remarkable because this was an adult male — they typically don’t do that,” said Remington Moll, an assistant professor in natural resources at the University of New Hampshire. “They’re usually settled down by the time they’re an adult.”

Researchers were curious about deer movement in those areas as a larger effort to track populations in the state and inform management. Moll was analyzing data gathered by the University of Missouri when “this massive movement [jumped] out” at him.

N17003 set out eastward from north of Kansas City until it hit Interstate 35, a major highway crossing Missouri’s northwest. The buck turned southward, following the road for a while before eventually crossing it and heading southeastward for a few weeks. It didn’t stop its trek until around Thanksgiving, when the buck reached Monroe County north of Columbia. A local landowner even managed to capture an image of the deer in question on a trail camera.

A landowner in Monroe County caught an image of the buck, N17003, near the end of its epic trip. Credit: Missouri Department of Conservation

All told, the deer had traveled about 300 kilometers on the ground, according to Moll and the co-authors of the study published recently in Ecology and Evolution.

“It was the longest we could find in the literature,” Moll said. The next longest adult male white-tailed deer movement they could find reference to in the literature was only about 50 kilometers, in which the deer seemed to be looking for cover in a relatively treeless part of South Dakota.

Younger deer are known to disperse from their birth areas into new territories to avoid inbreeding or sometimes in an effort to mate. They may also move when there is too much competition for mates. But even younger deer typically don’t disperse more than 40-60 kilometers away. And adults rarely move very far at all.

“It’s usually in the order of tens of kilometers rather than hundreds,” Moll said.

The deer’s dispersal is even more surprising because it crossed an interstate and several state highways, all during hunting season. But while the journey raises more questions than answers, it may have implications for the management of wildlife pathogens like the one that causes chronic wasting disease.

It’s unclear how many deer exhibit this behavior, whether it’s one in 700 as this project shows, or one in 10,000. But if an animal carrying CWD travels that far, it could bring the deadly disease that persists in the soil to new areas fairly quickly.

“It really broadens the scale of something like disease management,” Moll said.

N17003 never repeated its journey. Moll said it died in June 2018 in its new range around Monroe County, possibly of hemorrhagic disease, though the cause is speculative. But memory of the deer’s achievement lives on in Moll’s paper.

“The sheer scale of it was such that we thought we’ve got to draw attention to this,” he said.

Header Image: White-tailed deer rarely disperse more than 60 kilometers or so. Credit: Bob P. B.