Share this article

Wild Cam: Wildlife abundant in Chernobyl Exclusion Zone

Wildlife researchers drove through the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, which, 30 years ago, witnessed the world’s worst nuclear accident. They passed abandoned houses, many of which still had family photos hanging forlornly on the walls.

The researchers — including James Beasley who last year coauthored a study on the impact of radiation on Chernobyl’s wildlife — were out to track wildlife through camera traps in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone. “We tried to build upon our earlier work using a slightly more modern technique and something highly visual so that everyone can see these images,” said Beasley, a member of The Wildlife Society and senior author of a new study, which appeared in Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. Our most recent Wild Cam photo essay features some of the photos collected during this study.

Raccoon Dog. ©National Geographic/Jim Beasley/Sarah Webster

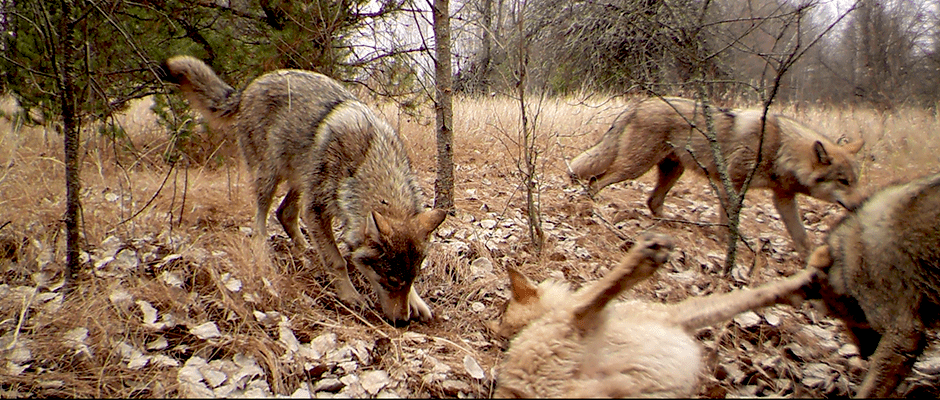

Beasley and his team, including lead author and graduate student Sarah Webster, placed remote cameras every three kilometers throughout all of the accessible roads within the Belarus side of the exclusion zone. They put a fatty acid scent at the stations in order to attract carnivores, which they primarily focused on for their research. “There’s very little published information on many carnivore species in the exclusion zone,” Beasley said, adding that raccoon dogs (Nyctereutes procyonoides) and wolves were most commonly observed.

Gray Wolves. ©National Geographic/Jim Beasley/Sarah Webster

Beasley and his team didn’t find any evidence to suggest animals were avoiding areas of high radiation contamination. Habitat characteristics were more likely to influence where they found the animals, he said. Beasley said he saw more evidence and signs of wolves in the exclusion zone than any other place he has ever visited.

The team collected enough camera trap data to develop models for four species including gray wolves (Canis lupus), red foxes (Vulpes vulpes), raccoon dogs and the Eurasian boar (Sus scrofa).

Eurasian boar. ©National Geographic/Jim Beasley/Sarah Webster

While Eurasian boars are not carnivores, they commonly visited the scent stations. The researchers found that Eurasian boars often traveled to the border of the exclusion zone where there’s an abundance of agriculture. “They commonly depredate crops in agricultural fields and they were likely using the edge areas more frequently to exploit that agriculture,” Beasley said. However, the team also found the boars in the most contaminated areas as well. “Radiation didn’t influence where we found them,” he said. “These data help to reinforce that previous study: Habitat is driving where we find these animals, not radiation.”

Eurasian Bison. ©National Geographic/Jim Beasley/Sarah Webster

Most wildlife in the exclusion zone are not managed since they are self-sustaining populations. However, the area is also home to some species of conservation concern such as the Eurasian bison (Bison bonasus). “We did detect them, both driving around the zone and on our cameras, but they were introduced to the exclusion zone and they are managed,” Beasley said.

Other species introduced to the exclusion zone include Przewalski’s horses (Equus ferus przewalskii), which are one of the most endangered mammals in the area. The researchers didn’t detect them in their surveys, mainly because the surveys weren’t targeting them, but did observe evidence of their presence while driving though the zone.

Red Deer. ©National Geographic/Jim Beasley/Sarah Webster

The team also detected other non-carnivores such as red deer (Cervus elaphus), which they had studied in their previous research. Here, a red deer stands next to an abandoned house.

Beasley is working to obtain funding to further study wildlife in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone. He has also fitted the area’s gray wolves with GPS collars as part of another project. “The next step for us is to get a better understanding of survival and reproduction of these animals,” he said.

Abandoned House. ©James Beasley, courtesy of the National Geographic Society

Despite the abundance of wildlife in the exclusion zone, the abandoned houses still hit close to home for Beasley, who said the message from this research is not that radiation is good for wildlife, but rather that human actions are potentially worse.

“Sometimes we lose sight of the human tragedy that has happened there,” he said. “When you drive through the exclusion zone, it’s incredibly beautiful from a wildlife perspective. But it’s also a sad reminder of human tragedy.”

This photo essay is part of an ongoing series from The Wildlife Society featuring photos and video images of wildlife taken with camera traps and other equipment. Check out other entries in the series here. If you’re working on an interesting camera trap research project and have photos you’d like to share, email Dana at dkobilinsky@wildlife.org.

Header Image: A pack of wolves visit a scent station on the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone. ©National Geographic/Jim Beasley/Sarah Webster