Share this article

Wildlife Featured in this article

- Canada lynx

- mountain lion

- black bear

- elk

- white-tailed deer

- mule deer

- snowshoe hare

- grizzly bear

- coyote

- red fox

Wild Cam: When humans are away, Glacier wildlife strays

The COVID-19 shutdown provided a natural experiment to understand wildlife behavior in Glacier National Park

When the COVID-19 pandemic shut down most activities—even recreation at some national parks—it was the perfect opportunity for researchers to study human impacts on wildlife behavior.

Alissa Anderson, a graduate student at Washington State University at the time, had wanted to add to previous research on Canada lynx (Lynx canadensis) occupancy at Glacier National Park in Montana using trail cameras. She and her colleagues decided that looking at how human recreation impacted wildlife behavior could be helpful to park administrators. Then COVID hit.

In the summer of 2020, the Blackfeet Nation closed access to the eastern portion of the park. But they did allow limited administrative access, including researchers following strict travel protocols. “It turned into a unique, surprising opportunity,” said Anderson, a TWS member who’s now a biologist with Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks.

Because Canada lynx researchers had already placed cameras in the park, Anderson and her team were able to compare wildlife presence before and after the closure while in the western portion, people continued to recreate, often in large numbers.

Anderson, who led the study published in Scientific Reports, found some clear wildlife responses to the absence of humans. She and her colleagues reviewed photos from 40 camera locations before and after the park closure, making note of how often animals were detected, at which locations and what time of day.

When the eastern part of the park was closed to the public, the researchers captured photos of species occupying areas where they usually weren’t found, like the mountain lion (Puma concolor) below taking a nap on a normally very popular trail.

When hikers were around, however, 16 of the 22 mammal species caught on camera changed what areas they used and when. “Most of the species had some kind of negative response to the open period,” Anderson said.

For example, black bears (Ursus americanus), like the ones below, used areas around trails less when the park was open than they did after the shutdown.

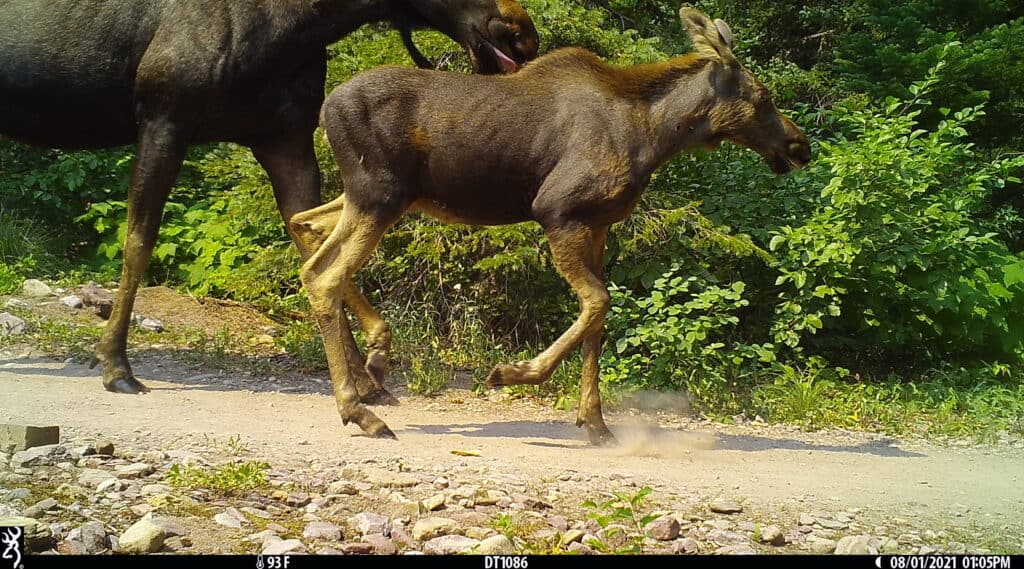

Elk (Cervus canadensis) and white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) also avoided trails when people were around.

The researchers also noticed other behavioral changes. Some species—like mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus), snowshoe hares (Lepus americanus), grizzly bears (Ursus arctos horribilis) and coyotes (Canis latrans), like the one below—became more nocturnal and less active during the day when people were around.

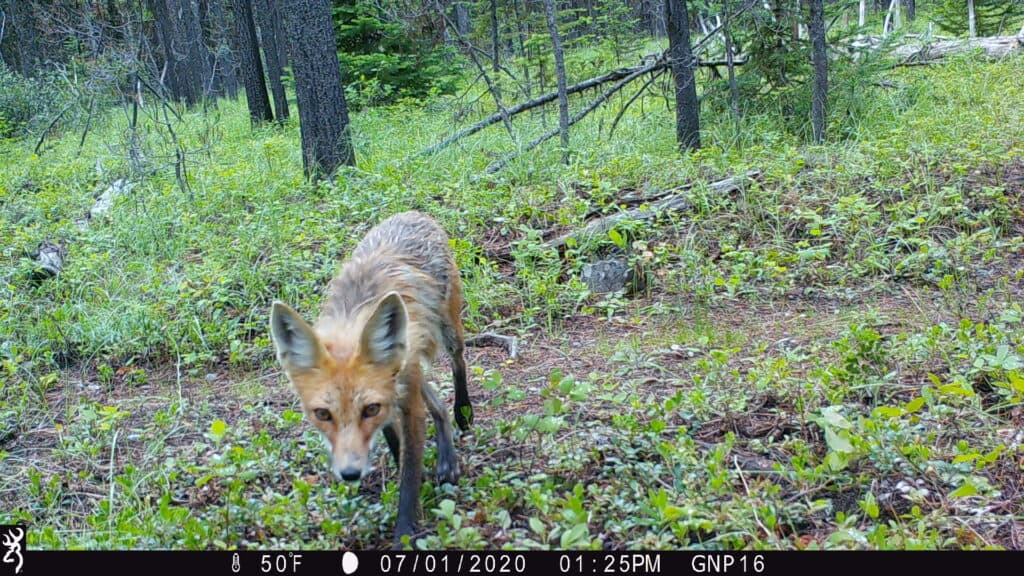

The researchers wondered if, by hindering predator movement, human presence led smaller prey to use areas close to trails more. But they didn’t find evidence of that. They did, however, find something similar to that phenomenon with red foxes (Vulpes vulpes).

Red foxes, like the one below, were more likely to be detected when humans were around. Researchers think may be attributed to coyotes—their competitors—decreasing their activity near people.

Despite these behavioral changes, Anderson said, more research is needed to find out if human presence affects animals’ fitness or survival.

Still, the research adds to the data national parks may want to consider in balancing human recreation with conservation. Anderson hopes it can help national park managers make decisions about things like opening new trails.

“This is another example of the kind of recognition we, as humans on the landscape, should have about how we change animal behavior just by being there,” Anderson said. “There is no hunting within park boundaries, no dogs that have negative effects on wildlife, just human presence.”

This photo essay is part of an occasional series from The Wildlife Society featuring photos and video images of wildlife taken with camera traps and other equipment. Check out other entries in the series here. If you’re working on an interesting camera trap research project or one that has a series of good photos you’d like to share, email Dana at dkobilinsky@wildlife.org.

Header Image: The COVID-19 shutdown provided a natural experiment to understand wildlife behavior in Glacier National Park