Share this article

Tracking 25 years of massive land conservation effort

It was raining when researchers fit a female wolf with an Argos radio tracking collar in 1991—one of the first times the technology had been used in such a way. The team captured the wolf in southern Alberta and nicknamed it Pluie, the French word for rain. After its capture, the team tracked the wolf as it moved more than 1,000 miles down into Montana, then westward though Idaho and Washington state, before traveling upward through British Columbia and back into Alberta again.

“Pluie blew everyone’s mind,” said TWS member Mark Hebblewhite, a professor of habitat ecology at the University of Montana. The female wolf had started near Banff National Park but had moved through a massive area, totaling 15 times the size of Banff over two years.

The wolf’s (Canis lupus) traverse revealed just how much habitat was necessary for conserving long-ranging species. “One protected area was not sufficient for a wolf population,” Hebblewhite said.

The Yellowstone to Yukon (Y2Y) project began with a goal of providing ample space for animals like Pluie. Faced with the decline of wild habitats necessary to conserve the massive migrations of wolves, elk (Cervus canadensis) and others, they set out to create continuous 2,000 miles of continuous habitat between the two areas. The area between the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem and Yukon includes five American states, two Canadian provinces and two Canadian territories. It also includes the territory of at least 75 Indigenous groups, according to the organization. Those involved on the project set out to work with hundreds of organizations including state, provincial, federal and Indigenous governments, conservation organizations, private companies and landowners to better protect areas in this massive western land corridor.

More than 25 years after the effort began, Hebblewhite and his colleagues measured how successful these efforts were in a study published recently in Conservation Science and Practice.

A mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) crosses a wildlife overpass in Banff.

Credit: Wendy Francis/Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative

The researchers realized it would be difficult to quantify conservation success in such a large project. Instead, they looked at the metrics of change in protected land in the past quarter century in the Yellowstone to Yukon land corridor.

They found that 108,000 more square kilometers are protected in the area today than prior to 1993. The largest single increase in protection involved the creation of the 64,000-square-kilometer Muskwa-Kechika Management Area in northern British Columbia. The next biggest was the expansion of Nahanni National Park Reserve in Canada’s Northwest Territories. When created in 1972, this park was only 4,766 square kilometers. But in 2009 the park was expanded to 30,050 square kilometers. Right next door to area is the Nááts’įhch’oh National Park Reserve, a 4,898-square-kilometer area protected in 2008. Yellowstone to Yukon also influenced the creation of four provincial parks in Alberta, and contributed to recent expansion of wilderness areas in Montana and Idaho.

On the southern side of the border, many conservation efforts focused on private land. These included the purchase of 130,000 hectares of timber land by The Nature Conservancy inspired in part by large landscape conservation vision of Y2Y.

This site of a proposed wildlife overpass would be the first outside a national park in Alberta. It lies just east of Canmore and the gates of Banff National Park.

Credit: Adam Linnard/Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative

The researchers compared the conservation pace of the land within the Y2Y corridor to land in overlapping provinces, territories and states outside the corridor. They found that the rate of conserved land inside the corridor increased over the last quarter century, while the land in those states outside the corridor either didn’t change or decreased.

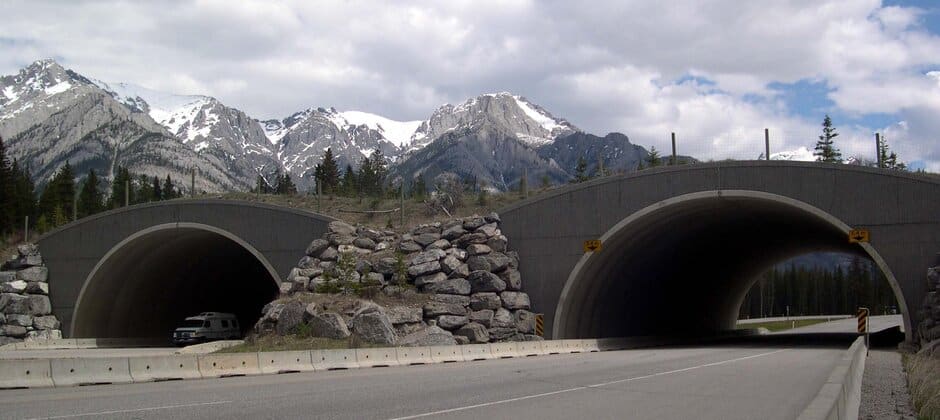

The team also looked at wildlife crossings on highways and roads. The first overpasses were built in Banff, and over the following years researchers found that the Y2Y area had more underpasses and overpasses than anywhere else in the world. Crossing infrastructure includes nearly 200 kilometers of fencing, 107 underpasses and 10 overpasses.

These crossings are especially important in connecting habitats, Hebblewhite says, since roads are a major killer of wildlife. “Growth of such wildlife crossings is evidence of global leadership for wildlife coexistence,” he said.

Finally, the researchers looked at how the ideas of conserving large contiguous tracts of land were breaking outside the shell of conservation science into the wider general public. They found a large number of popular science articles on these topics, as well as mention of large conservation on TV shows like “Grey’s Anatomy” or “West Wing.”

The efforts are ongoing. More crossing structures are in the works and getting approved. There are also signed commitments to create three new protected areas—the 55,850-square-kilometer Peel Watershed in the Yukon and two Indigenous-led protected areas in British Columbia: Qat’Muk at about 2,111 square kilometers and an endangered caribou (Rangifer tarandus) protected area that could be another 9,173 square kilometers. “With completion of these three new [protected areas], the proportion of the Y2Y region protected would exceed 22%,” the authors wrote in the study.

This would bring the region closer to the goal of having 30% of all U.S. land protected by 2030.

Header Image:

The Red Earth Creek wildlife overpass in Banff National Park.

Credit: Wendy Francis/Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative