Share this article

This hunting season, CWD stands at a disturbing benchmark

As hunters take to the forest this fall, the risks posed by chronic wasting disease are greater than ever.

Last February, a white-tailed deer that tested positive for the disease in Mississippi made that state the 25th in the country to confirm the presence of CWD, putting the United States at a grim benchmark.

“We’re at the halfway mark,” said John Fischer, head of the Southeastern Cooperative Wildlife Disease Study at the University of Georgia. Of all the diseases his organization studies, he said, chronic wasting disease is the No. 1 threat.

“This is a uniformly fatal disease,” he said. “All the animals that develop the disease will die from it. There’s no treatment, no vaccine and no practical live animal test. That leaves us with preventing the disease as our most effective disease management approach.”

For hunters, Fischer said, that means being cognizant of CWD’s presence, of regulations meant to keep it from spreading and the role they can play in addressing it.

CWD is a disease related to mad cow disease, a form of transmissible spongiform encephalopathy that causes degeneration of the affected animal’s brain. The disease can lead to emaciation and abnormal behavior before killing the animal, but those infected may show no signs of the disease for 18 months or longer.

First identified in captive mule deer in a research herd in Colorado in 1967, CWD first was found in the wild in a Colorado elk in 1981. The disease is spread by abnormally shaped protein particles called prions shed in feces, urine, or saliva, or through infected tissue contaminating the environment. Since its discovery, biologists have seen it spread through both captive and wild populations, escape from one to the other, and reach more and more states.

“In some of these states it’s been a single captive herd, the herd was destroyed, and CWD has not been detected again” Fischer said, “but in other states it’s a disease that’s endemic in free-ranging deer and elk and in some cases moose.”

Recent research suggests it’s beginning to affect population numbers, he said.

Limiting the transportation of live cervids may be the most effective way to address the disease, Fischer said, but it won’t work alone.

“What hunters can do is learn about the presence or absence of CWD in the areas where they hunt,” said Fischer, a professional member of the Boone and Crocket Club. Calling CWD “a significant wildlife health problem,” Boone and Crockett has issued a position paper that strongly encourages surveillance and management programs to target the disease in areas where it isn’t widespread and focusing on containment and control strategies in areas where it’s endemic.

Many states have restrictions on moving carcass parts that could contain infectious prions. For hunters traveling to hunt, that means being aware not just of the rules in the state where they hunt but of every state they pass on the way home.

Baiting and feeding can spread the disease, Fischer said, by encouraging the animals to congregate, and while the risk is fairly low, so can the use of lures that contain urine, which may be infected.

For hunters accustomed to being able to move intact carcasses and attract animals with bait and feed, these precautions can be hard to accept, he said, but they’re important in stemming the spread of the disease.

“One of my standard lines about CWD is, in a comprehensive and aggressive CWD management or prevention program, everyone’s ox gets gored,” Fischer said. “We have to get the message out to everyone concerned that this is a serious disease, and prevention and management methods are called for.”

The Boone and Crockett Club is a leading sponsor of The Wildlife Society.

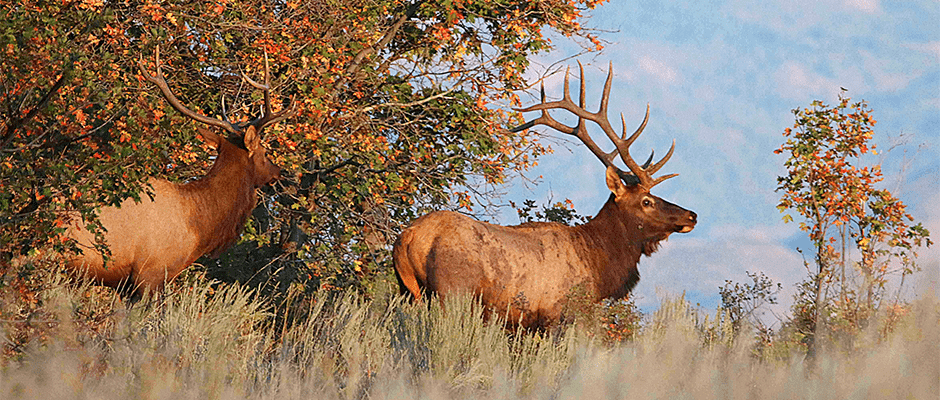

Header Image: Chronic wasting disease has been confirmed in 25 states, putting greater numbers of deer, elk and moose at risk. ©Jim Shuler