Share this article

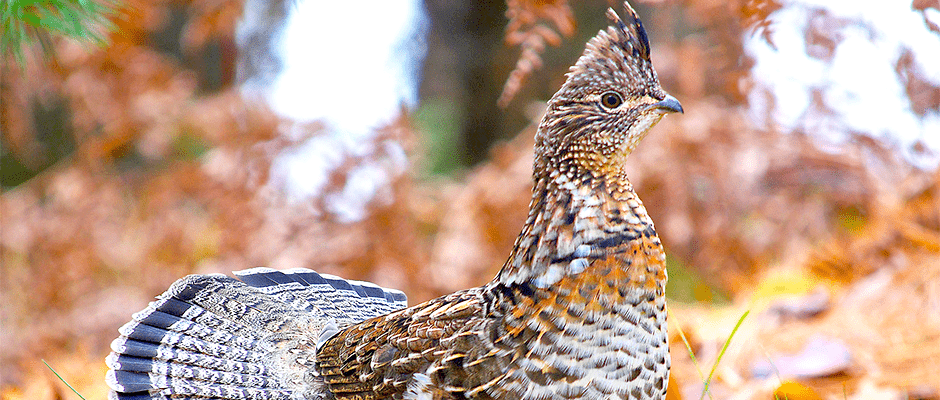

JWM study: West Nile could be impacting Pennsylvania grouse

A new study from Pennsylvania suggests that the West Nile virus may be partly to blame for the decline of ruffed grouse and could be undermining efforts to restore the bird.

Ruffed grouse populations have decreased by at least 30 percent in the Appalachians over the past three decades, largely because of losses in young forest habitat. But since the arrival of the West Nile virus in Pennsylvania 17 years ago, researchers found, ruffed grouse occupancy was most susceptible to decline in areas where West Nile infection rate in mosquitoes was greatest.

“West Nile virus infection in ruffed grouse might be contributing to its state and regional decline,” said Glenn Stauffer, lead author on the paper published in The Journal of Wildlife Management.

To understand why grouse populations are declining, Stauffer, then a postdoc at Pennsylvania State University, and his fellow researchers examined changes in ruffed grouse (Bonasa umbellus) occupancy in blocks designated by two Breeding Bird Atlas surveys from the late 1980s and early 2000s. They analyzed this information in the context of West Nile virus surveillance data the state Department of Environmental Protection obtained from 2001 to 2005 in mosquito pools across the state. West Nile virus was first detected in Pennsylvania in 2000. By 2003, it was present throughout most of the state.

“If the West Nile virus infection rate in mosquitos was high in a block, it was less likely to remain occupied or become colonized by ruffed grouse,” Stauffer said. “We haven’t directly demonstrated West Nile virus caused ruffed grouse declines, but ruffed grouse trends in occupancy are consistent with such an effect.”

Stauffer and his colleagues gained further support for the virus’ adverse impact on the bird’s populations by looking at 40 years of ruffed grouse flush counts from hunters throughout Pennsylvania. The hunters provided an indirect measure of grouse abundance by tallying the times they startled a grouse out of its habitat for every hour hunted — the flush rate.

“After the arrival of West Nile virus, flush rates dropped throughout Pennsylvania but do appear to have rebounded in some regions,” Stauffer said.

A recent laboratory study organized by the Pennsylvania Game Commission showed that the disease could kill ruffed grouse chicks, he said, which doesn’t bode well for their populations overall if West Nile virus is responsible for widespread population declines. Treating or vaccinating wild grouse isn’t feasible, and there are no known landscape-scale methods to treat grouse habitat.

“Unless we get a handle on West Nile virus in ruffed grouse, manipulating habitat to increase grouse populations might not be as effective as expected,” Stauffer said. “But good habitat is important, and if we can understand landscape patterns of West Nile virus, it might be possible to focus habitat restoration in areas where grouse populations have the best chance of increasing.”

TWS members can log into Your Membership to read this paper on Early View in The Journal of Wildlife Management. Go to Publications and then The Journal of Wildlife Management.

Header Image: A ruffed grouse traverses its Wisconsin habitat. ©Warren Lynn