Share this article

Wild Cam Series: Serengeti Wildlife

One of the largest camera trap surveys ever conducted used citizen scientists to take an inside view into discovering the ways animals in the Serengeti divide up their space and time and interact with each other.

The project originally started as research on how competing carnivores like lions (Panthera leo), leopards (Panthera pardus), cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus) and hyena species interact with each other as many of them compete for the same prey and species. But the enormous amounts of images that researchers collected — around 5.5 million at the latest count — were full of photos triggered by moving grass, cloud shadows or other things and required more work than researchers were able to handle. Alexandra Swanson, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Oxford who received her PhD in ecology, evolution and behavior from the University of Minnesota and the lead author of the study published recently in Scientific Data reached out to coauthor Margaret Kosmala for help. Kosmala, also a graduate student at the University of Minnesota, had a background in computer science and thought the best fit would be to incorporate citizen scientists to help sort through the wildlife photos and identify the species. They put the massive dataset into a project called Snapshot Serengeti, accessible on citizen science engine Zooniverse.

To provide a snapshot of this extensive project, we chose a series of photos taken from the 225 cameras set in a grid over 1,100 square kilometers. All images are credited to the Snapshot Serengeti database from where they were taken.

Image Credit: Snapshot Serengeti Database

The Snapshot Serengeti project was started by the University of Minnesota’s Lion Research Center, which has been tracking lion prides in the Serengeti for 48 years. Lions live in these prides to defend territory mostly from other lions, and males will stay in a pride for two to three years — “enough time for a generation of their cubs to grow to maturity,” Kosmala said.

Image Credit: Snapshot Serengeti Database

The study on carnivores found that there are a number of different complicated relationships that exist between large predators in the Serengeti that allow them to coexist. Researchers found that while lions and leopards both hunt at night, hyenas tend to feed during dusk and dawn, and cheetahs during the day. “It looks like it has more to do with time than it does with space,” Kosmala said. It can be more complicated than that, though — as illustrated by this shot of a lion and spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta).

Image Credit: Snapshot Serengeti Database

“Lions and hyenas eat the same things but hyenas will avoid places where lions are because lions are bigger,” said Kosmala. This photo is from a series of shots taken showing various predators like jackals, birds and others as well as the lions and hyenas feeding on the same carcass at different times with some overlap. “There are different pairs of carnivores and they avoid each other in different ways,” Kosmala said.

Image Credit: Snapshot Serengeti Database

But predators limit the competition between them by sometimes favoring different prey. While lions and hyenas favor wildebeest (genus Connochaetes), among other animals, cheetahs tend to favor Thomson’s gazelles (Eudorcas thomsonii), Kosmala said. Still, lead author Swanson wanted to see if there were fewer cheetahs around when there were a lot of lions. “While lions are bigger, fiercer, and kill cheetah cubs, she found that cheetah numbers do not decline because cheetahs avoid going too close to lions and that they reproduce again quickly after cubs are killed,” Kosmala said.

Image Credit: Snapshot Serengeti Database

Although the researchers initially set out to track carnivore interactions and spatial use patterns, the wealth of data they received means further studies on herbivores such as where the best feeding areas are and how some herbivores avoid predators in these areas. There are over 20 different species in the area, including this matriarchal herd of female African bush elephants (Loxodonta africana) and their young. “Elephants are important for grasslands (they pull down trees), but in our study they can be a real nuisance!” Kosmala said. “They are curious creatures that love to investigate our camera traps, often pulling them off the trees and tossing them around. We lose about 15 percent of our cameras each year to elephants, other animals, and weather damage.”

Image Credit: Snapshot Serengeti Database

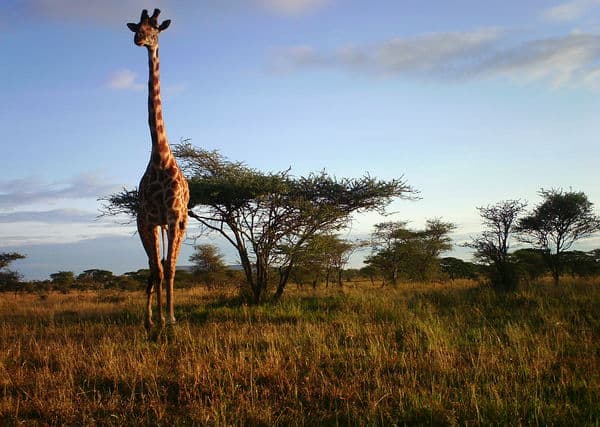

Some herbivores migrate through the Serengeti system while others are residents, hanging around the area all year. Giraffes (Giraffa camelopardalis) are among the resident species.

Image Credit: Snapshot Serengeti Database

Animals like this hippopotamus (Hippopotamus amphibius) might be active at night but don’t have to worry about large predators like lions due to their massive size. “They are surprisingly agile for their size and can roam miles each night in search of food,” Kosmala said of hippos.

Image Credit: Snapshot Serengeti Database

Zebras (genus Equus) and wildebeest migrate through the system, and are among the most abundant of the large animals in the Serengeti. “They perform a seasonal migration from the high-quality grasslands in the south during the rainy season to the always-green but less nutritious north during the dry season,” Kosmala said.

Image Credit: Snapshot Serengeti Database

It’s unclear what this impala is doing, but a user going by the name of “areinders” on the site dubbed the shot “impala antics.” Researchers are also now looking at how smaller antelope like dik dik (genus Madoqua) reedbuck (genus Redunca) and others interact and whether they bother each other. They’re also studying how the antelope interact with larger herbivores like hippos or giraffes. “Impalas are one of more than 20 plant-eating hoofed animals in the Serengeti,” Kosmala said. “They hang out in wooded areas and so have a different plant diet than those herbivores that spend most of their time on the open grassland.”

Image Credit: Snapshot Serengeti Database

Grasslands are typically flat and low — sometimes a problem when you’d like a camera trap to take a wider view of the landscape. Kosmala said that whenever possible, researchers set the cameras up on trees, such as the one casting a shadow on this male ostrich (Struthio camelus).

This photo essay is part of an ongoing series from The Wildlife Society featuring photos and video images of wildlife taken with camera traps. Check out other entries in the series by clicking on the “Wild Cam” tag below.

Header Image: Image Credit: Snapshot Serengeti Database