Share this article

Multiple males help female pheasants with parenting

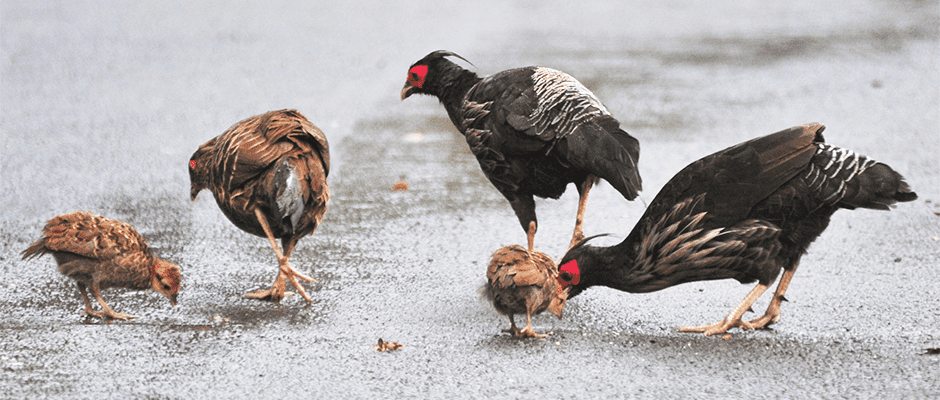

Few females are lucky enough to have a group of males doting on their offspring. But female pheasants in Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park are getting exactly that, thanks to an unusual set of circumstances that leave both females and territories in short supply. In this non-native population, kalij pheasants (Lophura leucomelanos) form family groups with one female and up to six males, all of whom cooperate to protect and feed the chicks.

“It is an indicator of how plastic the behavior of animals can be,” said Lijin Zeng, an ecologist at the University of California, Riverside and lead author of a recent study in The Auk: Ornithological Advances. “If we put our birds back into their natural habitat, they may behave just like the other birds over there.”

Kalij pheasants are native to Asia. While little is known about how they behave in their native forests, research suggests that the birds breed monogamously or in groups of one male and several females. Both breeding systems are common in the animal kingdom, allowing everyone involved to produce their own offspring.

But sometimes, the best strategy is to help someone else. Cooperative breeding — when adults help to raise offspring that aren’t their own — occurs in about nine percent of bird species, usually when older chicks return to help their parents raise a new brood. The helpers bide their time until mating opportunities open up, sometimes inheriting the family territory. In the meantime, they get some genes into the next generation by helping their siblings.

Such cooperation is relatively common in songbirds, which need all the help they can get to raise their bald, helpless chicks. In contrast, birds like ducks and pheasants can walk around as soon as they hatch, and they rarely help each other with parenting. Until now, only two species in the pheasant family were known to breed cooperatively.

Zeng and her colleagues began watching kalij pheasants in Hawaii in 2009. The study area had about 30 pheasant social groups, which the researchers tracked over three years. Most groups had multiples males, and only some of the males within groups were related. No group had more than one female.

All the adults helped watch for predators and fight off pheasants from other groups. They also helped the chicks forage, pointing at food with their beaks or handing it to the chicks directly.

“Except for one outlier, every single individual in the groups with chicks helped chicks by giving them food from beak-to-beak,” said Zeng.

To find out which males were reproducing, the researchers placed radio collars on 15 females and tracked them to their nests. Then, they collected material from inside hatched eggshells for DNA analysis. Most chicks were fathered by the dominant male in the group, but 17 percent were fathered by subordinate group members, and 14 percent were fathered by outsiders. This suggests that while it pays to be dominant, subordinate males also have some chances to mate.

The researchers can’t know for sure why kalij pheasants in Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park have adopted their unusual breeding system, but two factors probably contribute.

First, there aren’t enough females to go around. The study site has more than twice as many adult males as females, even though the sexes are balanced in nestlings. This may be because in kalij pheasants, males stay where they were born, but females fly away when they reach adulthood, says Zeng. The habitat in Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park is a lush forest surrounded by inhospitable lava flows. All the females that hatch there eventually leave, but apparently, few females from other forests ever find their way in.

The other explanation for the pheasants’ behavior is lack of space. Kalij pheasants are crowded at the study site, and not every male gets its own territory. By joining an existing group, subordinate males can increase their chances of inheriting a territory from a dominant male, perhaps fathering a few chicks in the meantime. Indeed, the researchers found that the dominant male in a group was usually the oldest, and when it died, a younger group member typically took its place.

“When densities are high, [animals] exhibit behaviors that they may not exhibit in their natural range,” said Dustin Rubenstein, a behavioral ecologist at Columbia University who was not involved in the project. Rubenstein praised the study for its combination of molecular and field work, and said the findings are consistent with other recent discoveries of cooperation in unexpected places.

“I think what’s interesting in this study is that it was in a group of birds where there’s not a lot of cooperative breeding. And, in fact, it’s predicted that you wouldn’t see it,” he said. “Cooperative breeding, we’re learning, is more common than we once thought.”

Header Image: A young male kalij pheasant in Hawaii shows a chick where to find food. Pheasants in this introduced population breed in groups of one female and one to six males. ©Lijin Zeng