Share this article

Migratory Birds Lack Adequate Habitat Protection

Migratory birds are always on the move and, as a result, rely on habitat protection — of breeding grounds, nonbreeding grounds and stopover areas.

“I realized that in large conservation initiatives, we’re just not seeing that happen,” said Claire Runge, lead author of a recent study published in the journal Science. Migratory birds have faced significant declines over the past three decades and Runge, a researcher at the National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis at the University of California-Santa Barbara, and colleagues wanted to determine the extent to which migratory bird habitat is protected across the globe.

After looking at a database of protected areas for both non-migratory and migratory birds around the world developed by Birdlife International, a global partnership of conservation organizations that strive to conserve birds, the researchers developed maps of migratory routes and found that only 9 percent of 1,451 species of migratory birds receive adequate protection of their habitat across their entire range. In some species, it was their breeding grounds that weren’t receiving adequate protection and in some species it was their nonbreeding grounds or the places they use to get between the two that weren’t doing so well.

“It was really surprising because I expected that breeding grounds would always be more protected than their nonbreeding grounds,” Runge said. “When we looked at threatened species of migrating birds, they were even worse.”

A mere three percent of threatened migratory birds were adequately protected. In order to determine if the birds are adequately protected, the researchers set a target for protected area coverage based on the size of their range. Species with a smaller range had a higher target for protection than species with larger ranges as they are more vulnerable to threats, Runge said. One of those threatened birds is the far eastern curlew (Numenius madagascariensis) that migrates from Siberia and Australia, stopping over at sites in South China and North and South Korea.

“This study seems like it has a depressing message, but there’s cause for hope,” Runge said. This is because there’s still a chance for countries around the world to protect these areas, which they’re already starting to do, according to Runge.

“Unless you consider migratory species, these protected areas are put in the easiest places where there aren’t any people, where it’s cheap and there isn’t any agriculture,” she said. “For migratory species, we need to consider that those areas might not be in the best places. We want to try to fill those gaps for migratory species across the world.”

Runge hopes that this study will help get the message out that it’s important to focus on key protected areas. “We don’t know where the key places are, but we can make guesses. It would be great to have a lot more information on the key locations,” she said.

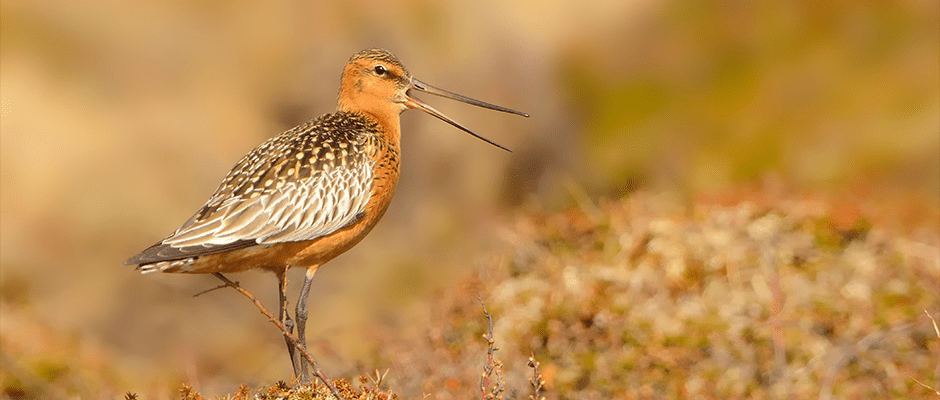

Header Image:

The bar-tailed godwit (Limosa Lapponica), one of the migratory birds in the study, undertakes some of the longest endurance flights in the world, but suffers from the loss of its stopover habitat in the Yellow Sea region of the East Asian-Australasian flyaway.

Image Credit: Martin Pelánek