Share this article

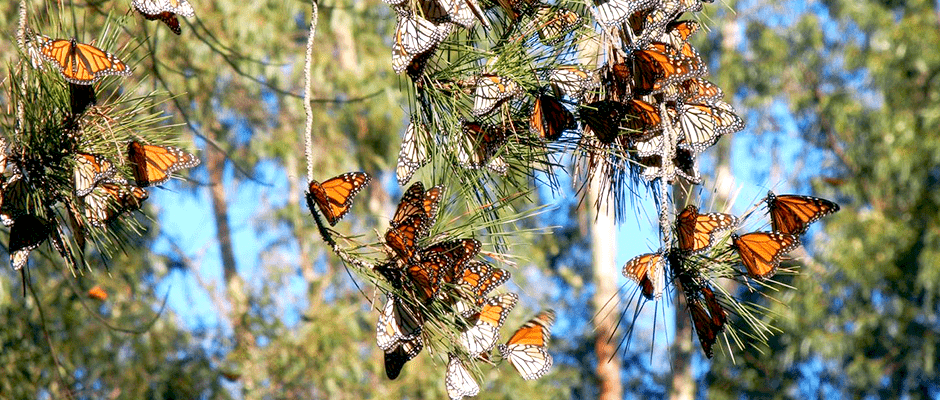

West Coast monarchs face steep decline

Monarch butterflies that overwinter on the West Coast of North America have declined from the millions 30 years ago to only 300,000 today, according to new research, raising concerns that these populations are faring far worse than those in the East and could vanish altogether within decades.

“If we don’t change something, monarchs are unlikely to persist as we know them in the U.S.,” said Elizabeth Crone, a professor of population ecology at Tufts University and coauthor of the recent study published in Biological Conservation.

Monarchs have received a lot of attention in general, Crone said, but the West Coast populations have been less studied and their decline has been hard to quantify. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which funded the study, is considering whether to list them as threatened under the Endangered Species Act.

Crone’s coauthors pulled together numbers collected by hundreds of volunteers who participated in the Xerces Society’s Western Monarch Thanksgiving Count since 1997 and from amateur and professional counts conducted since the 1980s to predict the extinction risk of monarchs that overwinter in forested groves along coastal California.

They estimated these West Coast monarch populations ranged between 3 million and 30 million in the 1980s before dwindling to only about 300,000 today — a decline far steeper than their eastern counterparts. Over the next 20 years, they estimated, these butterflies face a 45 to 70 percent chance of disappearing as we know them.

“That is not a very precise estimate, but it’s a big enough number to be scared,” Crone said.

Monarchs act as pollinators, and because they are toxic to some bird species, Crone said, they deter certain birds from consuming other butterflies that look similar to them, raising concerns about ecosystem impacts if they disappear.

The butterflies face threats ranging from a loss of milkweed to pesticides to drought resulting from climate change, she said, but conservation actions could reverse the downward trend.

“It’s not just about documenting the decline, but figuring out how to recover them,” she said. “Working together for their recovery is possible.”

Header Image: Monarch butterflies on North America’s West Coast have declined more than previously known and face greater risk of extinction than eastern monarchs. ©Candace Fallon