Share this article

U.S. parks may become more vital to birds as climate changes

National parks preserve habitat for hundreds of avian species in the United States. Researchers anticipate these protected areas will host even more extensive bird communities as climate change keeps transforming the landscape.

“Climate change is a big driver in bird species assemblages in national parks,” said Joanna Wu, lead author on the study published in PLOS ONE. “National parks will be increasingly critical sanctuaries for birds seeking a suitable climate.”

A National Audubon Society biologist, Wu and her colleagues modeled how 513 bird species would alter their distributions in 274 national parks throughout the country if atmospheric greenhouse gases persist into the middle of the century. They relied on the North American Breeding Bird Survey and the Audubon Christmas Bird Count and considered possible changes in temperature and precipitation using observations from the early 2000s.

“One-quarter of birds in America’s national parks could be different by 2050 if carbon emissions continue at the current pace,” Wu said, with parks at higher latitudes in the Northeast and Midwest experiencing the most turnover.

“As birds move to track the climate, parks may gain species along with all the ecological interactions, habitat availability and other complications that come with that,” she said. “In winter, as the climate becomes warm enough, an average of seven species per park may not need to migrate south anymore.”

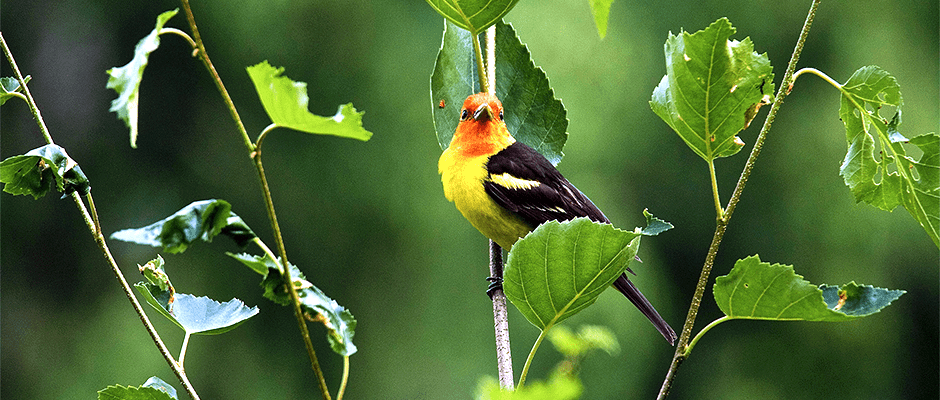

Arizona’s Grand Canyon National Park could see new raptors, such as the white-tailed kite (Elanus leucurus), gray hawk (Buteo plagiatus) and Harris’s hawk (Parabuteo unicinctus), Wu said. Mid-elevation species like the western tanager (Piranga ludoviciana), pygmy nuthatch (Sitta pygmaea) and red-naped sapsucker (Sphyrapicus nuchalis) could colonize the coniferous forests of Colorado’s Rocky Mountain National Park.

Research going back to the 1960s shows birds are wintering farther north than in previous decades, Wu said, which supports the finding that more species could stay in U.S. national parks as climate change moderates the colder months.

“Management requires adaptive thinking, so we can’t manage for static species assemblages,” she said. “Climate change is happening at a rate that’s unprecedented, so you have to manage for a moving baseline and changing set of ecological conditions based on these large environmental changes. Parks that are going to see a lot of change in species can increase habitat and promote corridors and native plants to allow species to disperse better.”

Wu’s team is now upgrading its climate models with habitat projections and finer spatial data. This summer, Audubon plans to start a nationwide citizen science count for bluebirds (Sialia spp.) and nuthatches (Sitta spp.) to corroborate their predictions of these animals’ substantial range shifts under climate change.

“The only way to know if projected changes are happening is by monitoring birds,” Wu said, “and that’s the best way to guide management efforts.”

Header Image: A western tanager rests on a plant in northwest Washington. ©Jerry McFarland