Share this article

TWS2021: AI image recognition could be the future of wildlife management

Image recognition technology could help with wildlife management, but the products still need some fine tuning.

“We saw lots of possible implications if this technology would work,” said TWS member and Arkansas Chapter Past-President Becky McPeake, a professor of wildlife education at the University of Arkansas who works on ways to control invasive feral pigs (Sus scrofus).

When McPeake attended the International Wild Pig Conference held in Oklahoma one year, she learned about the WiseEye game feeder, a device created to automatically recognize wildlife species on camera. The company was interested in exploring if its technology could be used to manage feral pigs. The animals a massive problem in the U.S., causing tens of millions of dollars in damage to crops and destroying native ecosystems.

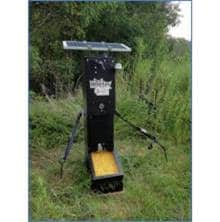

The device is about the size of a tall newspaper box seen on a street corner. It has a camera and doors to a food container at the bottom that automatically open if the right species enters the camera’s plane of view. Algorithms programmed into the device can recognize different species that approach the doors and only open for certain species, allowing access to the feeding compartment.

McPeake and Rachel Lipsey, a project and program specialist at the University of Arkansas and also a TWS member, wanted to see if the device could be used to deliver poison- or contraceptive-laced food to feral swine after recognizing them on the camera. But they had to make sure it worked properly, since they wouldn’t want to accidentally deliver poison or contraceptives to the wrong species. They describe their research on a poster presented at The Wildlife Society’s virtual 2021 Annual Conference.

The WiseEye device. Credit: Becky McPeake

In a much safer experiment, they bought six of the devices and programmed them to keep the doors open to feed corn to white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) and to close the doors when raccoons (Procyon lotor) or crows approached. The team decided to conduct the experiment at a golf club near Roland, Arkansas where chronic wasting disease had not yet been detected from October 2018 to April 2019. If deer congregate around the device here, they wouldn’t have the added issue of increasing disease spread since CWD wasn’t detected there.

The device could also deliver an electric shock to raccoons, scaring them away at the same time as closing the doors.

The researchers encountered a couple of problems right away. One issue was that the solar panel that powered the device wasn’t big enough in the beginning and had been placed in an area with a little too much shade. The researchers had to rely on back up batteries in those cases.

The main concern was that while the image recognition mostly identified deer, it wasn’t always accurate. At one point the machine misidentified Lipsey as a deer while she was bending over clipping vegetation in the camera’s view, for example. The machine also apparently misidentified a dog as a bear in another case.

Lipsey said the concern with these cases is that if the machine was used to deliver poison, it might accidentally kill non-target animals instead of feral swine.

The technology confused researcher Rachel Lipsey for a deer in this case. Credit: Becky McPeake

They also found that raccoons had a high tolerance for getting shocked. The crafty creatures learned to pry open the closed doors quickly and steal food in some cases. McPeake noted that if raccoons weren’t deterred by the electrical jolt, something larger like a bear would hardly be dissuaded.

“If a shock wasn’t able to ward off a raccoon, well then…” she said.

While she wouldn’t yet use it in cases requiring precision such as poison delivery, there may be other uses for the device in wildlife management. She also hopes that the technology will continue to improve, and is optimistic about future uses.

Both researchers would like to do follow up studies—perhaps using other more reliable power sources.

“You need to be able to recognize what’s in front of you if you’re using poison,” Lipsey said

Header Image: WiseEye technology was trained to recognize white-tailed deer and other animals. Credit: Artur Pędziwilk