Share this article

TWS2020: Protective pesticides for trees may harm frogs

Pesticides that are used to stymie the spread of invasive insects eating their way through eastern U.S. forests may be affecting wood frog development nearby.

Hemlock woolly adelgids (Adelges tsugae) are an invasive insect that eats through hemlock stands and changes the makeup of wildlife ecosystems. While some researchers have shown that other predatorial insects may be used to fight these adelgids, a common management technique involves injecting infected trees with neonicotonoid pesticides, either directly or spraying the chemicals around trees and allowing the roots to absorb them.

It’s cheaper to spray the areas around the stands of hemlocks than to inject individual trees. But the cheaper technique may cause more environmental contamination, as the neonicotonoids can run off into nearby ponds or waterways where young wood frog tadpoles begin their lives.

“This is a really important life stage to keep track of,” said TWS member Cassie Thompson, who resented her research in a video at The Wildlife Society’s virtual 2020 Annual Conference.

Researchers took egg masses from wild wood frogs. Credit: Cassie Thompson

Thompson, a PhD student in conservation ecology at Ohio University wanted to find out if these chemicals were getting into the aquatic systems in the areas they were being used in Ohio. In her presentation, Thompson described ongoing work looking at the ways that the pesticides are affecting wood frogs (Lithobates sylvaticus) development.

She and her colleagues found wild wood frog egg masses, and then placed them in two different tanks. In one tank, they exposed tadpoles to similar levels of neonicotonoids found in the wild near sprayed hemlock. The other tank didn’t contain pesticide.

After comparing the two, they found that the exposed tadpoles took longer to reach metamorphosis than the unexposed amphibians, and unexposed tadpoles survived to the adult stage.

Researchers chased frogs around this circle with their hands until they ran out of energy to determine endurance. Credit: Cassie Thompson

But they were surprised to find the exposed tadpoles performed better in endurance tests after changing to frogs than frogs that had never been exposed. “That was kind of an unexpected outcome,” Thompson said, adding that it might be because they spent longer in the development phase and emerged larger, or that since more of their companions died in the tanks, the survivors had more resources.

While frogs in the wild could become exposed to the neonicotonoids as tadpoles in ponds, they might also encounter the pesticides as adults while hopping through treated soil and leaf litter. The pesticide has a long half-life and can last in the soil for more than 300 days, Thompson said.

So they ran another set of tests in which they exposed frogs from both groups to a new concentration of the pesticides similar to those found in the soil in treated areas. They ran new endurance tests on the amphibians, which consisted of having frogs hop around a circular enclosure until they ran out of energy.

The team found that the wood frogs exposed to pesticides as tadpoles had greater decreases in performance when re-exposed as adults.

“It was kind of a double-whammy,” Thompson said.

They also dissected some of the frogs after the initial experiments and found that exposed frogs showed a 10% decrease in males compared to unexposed frogs. This meant the neonicotonoid-exposed frogs had a more skewed male-to-female sex ratio.

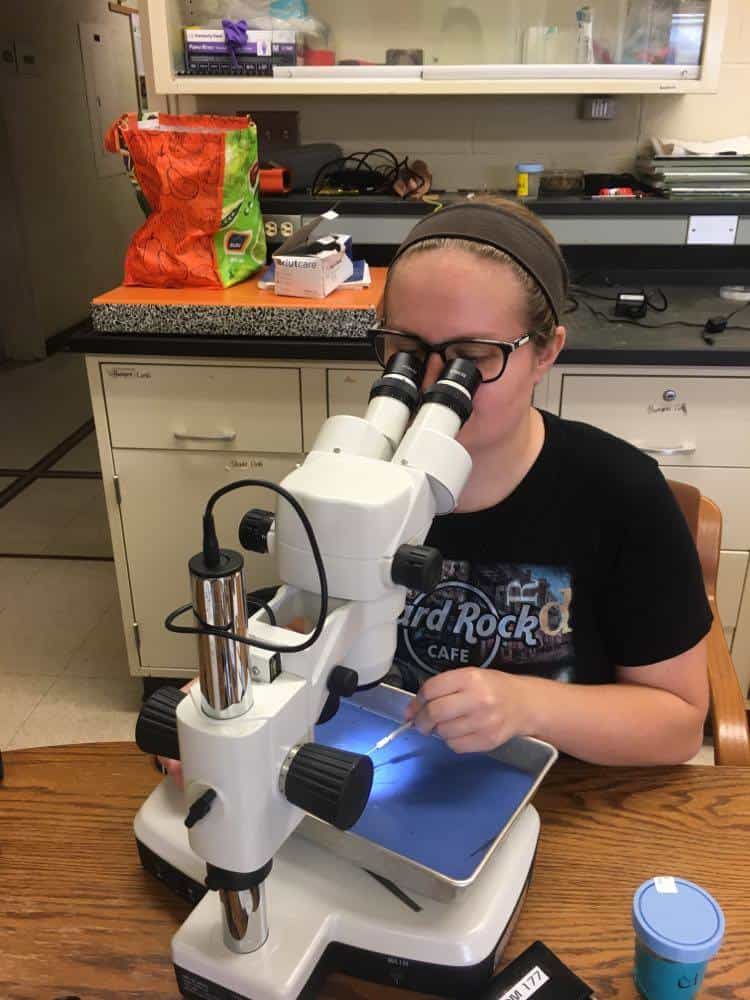

Undergraduate student Megan Sweeney examines wood frogs to determine sex. Credit: Cassie Thompson

Thompson said the research has direct management implications. For example, the potential effects the pesticide could have on amphibian populations means that it might be worth investing more in injecting hemlocks with the neonicotonoids directly to protect them from woolly adelgids.

“The results of this work will help better inform and help managers make better decisions,” she said.

This research was presented at TWS’ 2020 Virtual Conference. Conference attendees can continue to visit the virtual conference and review Jones’ paper for six months following the live event. Click here to learn about how to take part in upcoming conferences.

Header Image: A developing wood frog tadpole. Credit: Cassie Thompson