Share this article

Trophy hunting may imperil species already at risk

A group of researchers is calling for “extreme care” in managing trophy hunting after finding that the harvest of males that hunters worldwide choose could contribute to extinction in some species if not properly managed.

By targeting animals with large horns and other prized features, researchers found, trophy hunting can “lead to extinction” by removing the fittest genes in populations trying to adapt to increasing environmental pressures.

“Given the current changes happening globally,” the authors wrote in Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, trophy hunting “should be managed with extreme care whenever populations are faced with changing conditions.”

Since it only targets males, wildlife managers have widely supported trophy hunting because of its limited direct impacts on population numbers and the funding it can provide for conservation efforts. But using an individual-based model, researchers found that trophy hunting could have long-term population consequences for species undergoing environmental changes.

“They’re all facing changing environments, habitat loss and conflict with local populations,” said Rob Knell, lead author on the study. “If we add selective harvest when they’re already stressed, it could be the straw that breaks the camel’s back.”

In North America, most harvested species are well-managed, Knell said, but in some cases, trophy-hunted males are taken before they reach their reproductive peak and get an adequate opportunity to pass on their superior genes, he said.

“Removing those males is not a good idea,” Knell said, because it makes it more difficult for their populations to adapt to ecological disruptions over the following generations.

The risk is even greater in regions with poor wildlife management, he said. In Africa, many species being pushed closer to extinction by poaching, human-wildlife conflict and shrinking habitat “are already overhunted and having lots of high-quality males removed,” Knell said.

A reader in evolutionary ecology at Queen Mary University of London, Knell and his colleagues used computer simulations to examine how mammal populations facing unstable environmental conditions over time respond to trophy hunters taking fine, evolutionarily fit males through selective harvest.

“Even when you’re only removing 5 percent of the males, if the environment is changing and the population is having to adapt, then removing high-quality males can lead to extinction rapidly,” Knell said. “Not only are you removing the males best adapted to the environment. You then have the males not so well-adapted to the environment getting all those matings and spreading their not-so-good genes.”

Given the pervasive implications of climate change for temperature, rainfall and resources, Knell said, these findings “raise a big red flag” for wildlife populations subjected to trophy hunting.

“Until now, people have assumed that because you’re removing a small proportion of the population and the individuals you’re removing are males, the population growth rate’s not going to be affected, that selective harvest is unlikely to have serious consequences if it’s properly managed,” he said. “That assumption is not safe.”

Certification marking sustainable trophy hunting outlets could help hunters secure these populations into the future, Knell said.

“If you have an age limit and only remove males that already had a couple good chances to breed, quality males get to spread their genes,” he said. “It would be a good idea to extend that to anything that’s trophy-hunted to mitigate the bad effects of removing those males.”

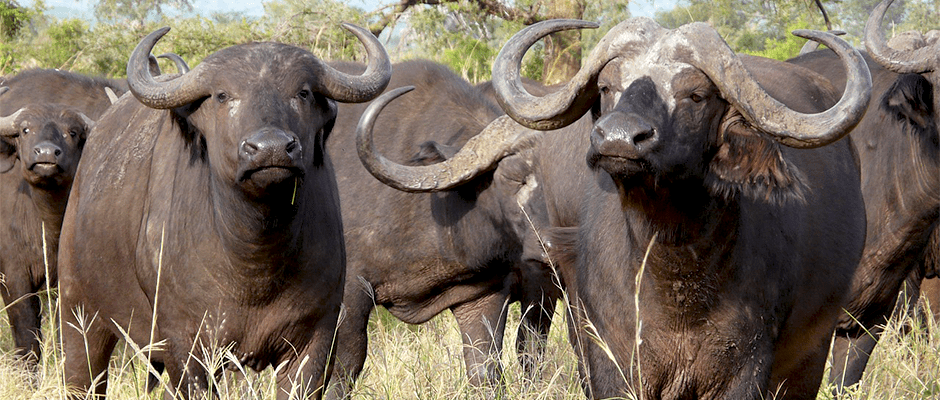

Header Image: Cape buffalo, which are trophy-hunted for their massive horns, gather on the African savanna. ©markjordahl