Share this article

Special JWM section highlights waterfowl conservation

Waterfowl conservation is a unique realm of wildlife management, and now it has its own journal issue to highlight it. One hundred years after the Migratory Bird Treaty Act was passed to protect North America’s avian populations, Chris Williams, a wildlife ecology professor with the University of Delaware, and his colleagues compiled a February special section of the Journal of Wildlife Management.

The Wildlife Society spoke with Williams about this issue, “Celebrating Waterfowl Conservation,” which contains four papers spotlighting the triumphs and hopes arising from a century of efforts on the ground. Our conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

What inspired this special section, and what is its purpose?

Five years ago, I was invited to The Wildlife Society conference in Winnipeg. I gave a “Spark” talk about reaching the 100th anniversary of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act in 2018 and the advances made for waterfowl in those 100 years.

By signing the act, the United States and Canada increasingly had to think about landscape-scale questions. To regulate the harvest of migratory species at the international level, we would need better population estimation, understanding of harvest dynamics, organization at the landscape level across the continent and habitat conservation. Having all those things helped lead our discipline of wildlife management forward.

In our infancy in the early 20th century, there were a handful of naturalists, but they had little scientific background to think about the application of management and conservation. I said to TWS, look at where we started in the 1800s, where wildlife population were in a terrible state. But look how far we have come over the last 100 years as a profession.

We are faced with greater challenges today as the human population continues to grow and the complications of our resource use puts more pressures on the planet. It’s daunting for the next generation of scientists to figure out how we are going to make it through the next 100 years. But those first wildlife biologists rose to the challenge, and we can, too.

After delivering my Spark talk, I decided the best thing we could do for the 2016 North American Duck Symposium was to hit those themes in our plenary sessions each morning. The first day was to celebrate the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, discuss the history and all the things we have accomplished over the last 100 years. During the second day, speakers discussed how we can better connect research and management, apply what we learn and build partnerships. The third day, speakers talked about the historical advancements in population estimates as well as the new field of integrated population modeling. On the fourth day, speakers discussed the future for revisions to the 1986 North American Waterfowl Management Plan, created as a concerted effort across the continent to set benchmarks by which we can continue to improve waterfowl populations and habitat.

We wanted to highlight those four central themes in celebration of that 100-year anniversary the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. We brought that idea to [JWM editor] Paul Krausman and asked if he would be interested in doing this as a four-part paper.

What would you like readers to take away from it?

Waterbirds are the one suite of species showing an average increase in relative populations over the last few decades. I believe the research base and cooperation among so many partners are huge drivers behind being able to protect wetlands and having enough scientific knowledge that we’re making smart decisions. We’re trying to provide a framework by which we can make a real difference on the planet. The take-home message is that we’re here to celebrate what we’ve accomplished, and we’ve set up the infrastructure, hopefully, that we can adaptively continue to make progress into the future.

In your editor’s message, you outline four dominoes that waterfowl conservation has effectively toppled over the past century. Tell me more about their significance.

When the Migratory Bird Treaty Act was passed, for huntable waterfowl, there had to be regulated hunting seasons. To have regulated hunting seasons requires that you know population estimation and harvest dynamics. Those are dominoes we’ve got to tip over so we can make smart decisions.

For the third domino, I talked about landscape-level organization. For species in one state one day and in another state another day, the act would require federal and international oversight. Moving regulation from individual states to a partnership between the U.S. and Canada — and, eventually, Mexico, Russia and Japan — was a new concept. While complex, this cooperation changed the face of modern-day landscape-level conservation.

Last, to promote landscape-scale waterfowl populations, it was critical we also promoted a mechanism where habitat conservation programs could be initiated. Through governmental habitat conservation programs and the tremendous private efforts from Non-Governmental Organizations like Ducks Unlimited, habitat goals could be achieved.

All four dominoes had to fall by the direct push of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act to assure that long-term population and habitat sustainability could be achieved.

How do you think the special section turned out? What feedback has it received?

It’s great. What is especially rewarding is hearing from fellow faculty members that this provided a centralized information base they can easily pass on for their students to read about our history, innovation and goals and be better inspired for their future.

Going forward, what are your hopes for waterfowl conservation?

I am hopeful we’ll continue to move in the right direction. We are faced with unparalleled dangers with human population growth, resource extraction, and climate change on the horizon. But when you have a well-integrated and adaptive system, open to a lot of viewpoints and different ways of solving problems, it makes us nimble. It allows us much more flexibility to address those conservation concerns even in the worst-case scenarios. While there are reasons for us to be very scared, I remain extremely optimistic that we can continue to be successful.

TWS members can log into Your Membership to read this special section in the Journal of Wildlife Management. Go to Publications and then Journal of Wildlife Management.

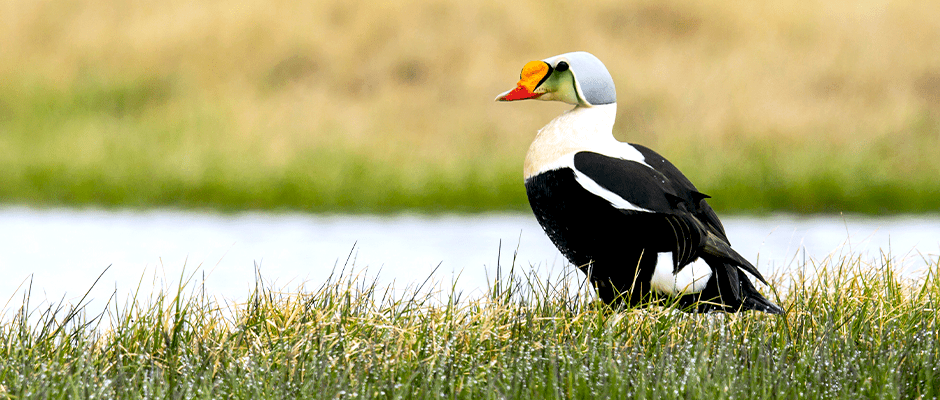

Header Image: A king eider sitting on the banks of Barrow, Alaska. ©Mick Thompson