Share this article

Shell disease may hamper pond turtle recovery

A newly described syndrome that causes lesions on turtle shells may be slowing the impacts of recovery efforts for northwestern pond turtles in Washington state.

“The shell disease is probably shortening the lives of our turtles, and that means they may not reach their full reproductive recovery,” said Katie Haman a wildlife veterinarian at the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife who works with the western pond turtle health team and recovery effort.

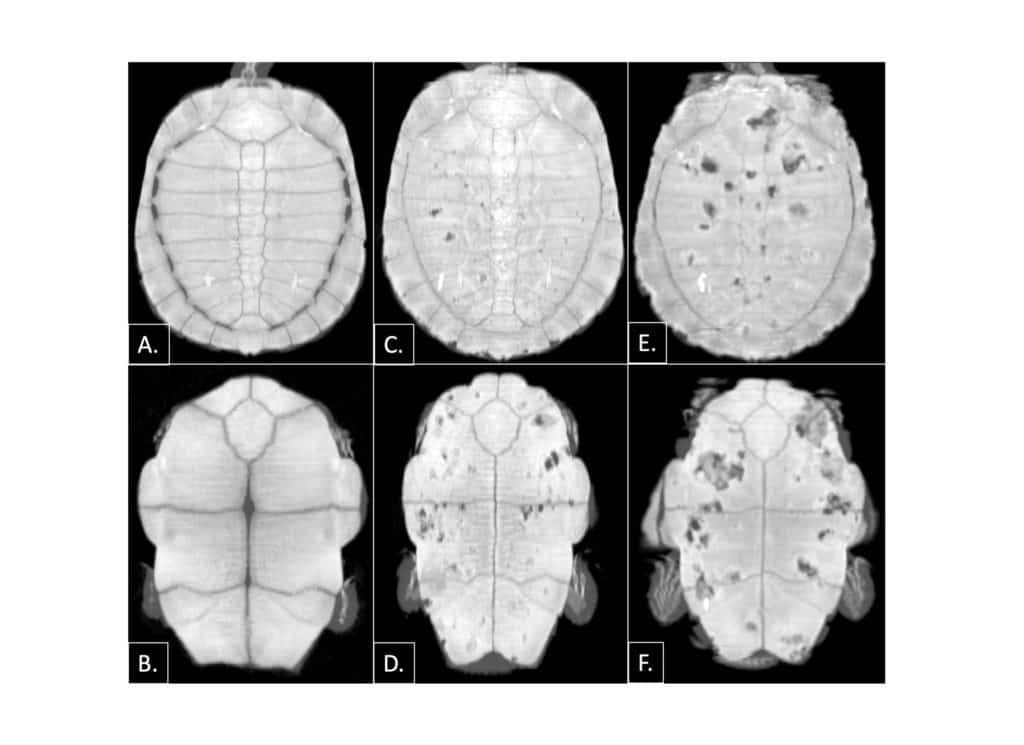

CT scans of turtle shells reveals boney lesions known to be associated with the shell-eating fungus. ©Haman et al., 2019

Northwestern pond turtles (Actinemys marmorata), which are endangered in Washington state, disappeared from much of their native range in the state by the 1980s due to a respiratory disease and the loss of habitat. Invasive species like bullfrogs (Lithobates catesbeianus) also feast on turtle hatchlings, making it difficult for numbers to bounce back.

Ongoing recovery efforts involve head-starting turtles — hatching and raising babies with partners at the Oregon Zoo in Portland, Oregon and Woodland Park Zoo in Seattle for the first year or two of their lives before releasing them into wild populations. This practice allows the turtles to survive the dangerous early years of their lives and grow large enough to avoid predation from bullfrogs and other predators.

“Initially this was considered a pretty big success,” Haman said. The turtles had recovered from a few hundred individuals at two sites to thousands of turtles at six sites mostly thanks to head-starting.

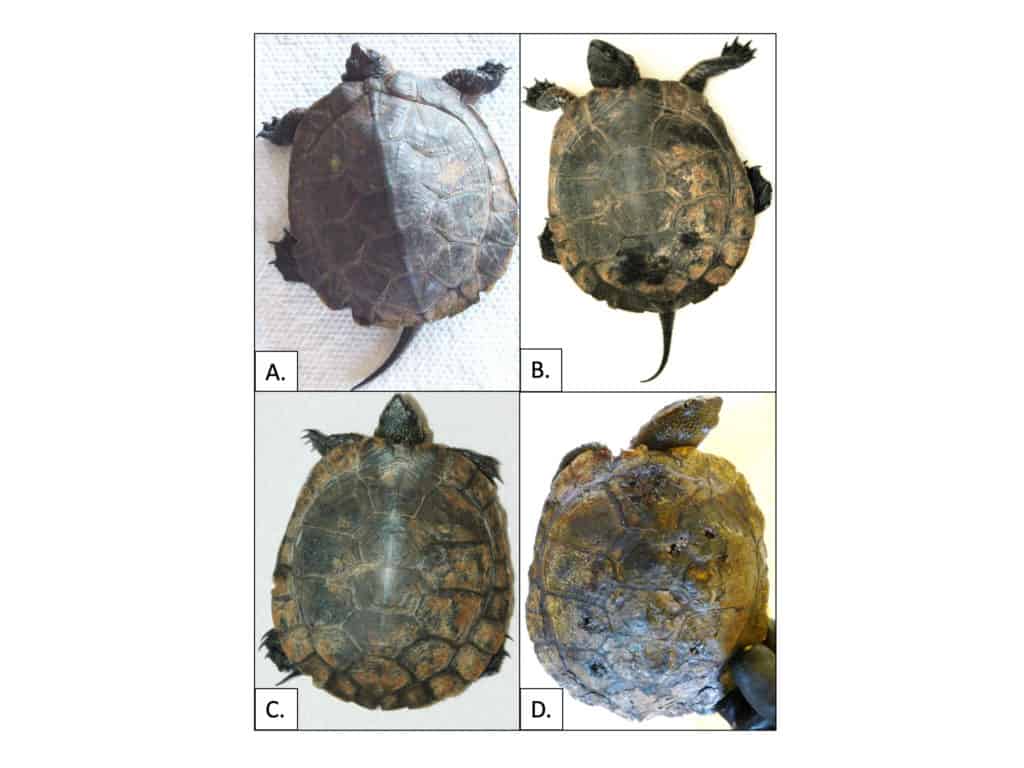

But in 2012, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife biologists began to notice some of the reptiles’ shells didn’t quite look right. Many displayed lesions. In subsequent research, other scientists attributed the lesions to a fungal-associated disease and found possible examples of this fungus-associated shell disease in other species going back at least to the early 2000s. While the disease seemed to affect turtles from around the U.S. and even mata mata turtles (Chelus fimbriata) from South America, most of those affected were captive at some point.

A turtle afflicted with the shell eating fungus. ©Haman et al., 2019

“It’s been in our turtles for quite a while — it’s just taken us some time to identify it,” Haman said.

The disease doesn’t kill turtles from what the researchers can tell — at least not right away. Haman said the turtles may not die until at least a decade after shell disease begins, and once they do, it’s not clear whether the disease itself kills them or whether the shell degradation allows access for other deadly infections. An ongoing study using tracking devices is looking to track the reproductive success of turtles which have the disease, whether severe cases or mild.

Researchers are also looking at how well turtles do after treatment, which include surgical removal of dead or infected tissue around the lesions, and using antifungals and antibiotics, to see if these methods are actually working.

Without CT scans it’s hard to tell if the turtles have the shell disease until they’ve been afflicted for some time. The turtles may appear outwardly healthy, but CT scan can show severe lesions.

“We don’t see shell disease in our turtles until they are five to seven at least,” Haman said, but added that the researchers are currently on the lookout for early signs of the possible fungal infection, including flaky keratin on their shells.

The prevalence of the disease is quite high among the turtles they head-start: Between 65% and 85% of Washington’s western pond turtles have shell disease, based on CT scans.

“I do think there is a component of captivity that makes these turtles more susceptible to this disease,” she said, but researchers have yet to pinpoint the cause. A change in water filtration in captive turtle ponds has helped reduce the prevalence of the fungus assumed to cause the disease to 45% to 60% among head-started turtles, though.

In some ways, the discovery of the disease has helped recovery efforts, Haman said, because researchers have placed more focus on recovery and improving husbandry of the turtles.

“We’ve really spent a tremendous time and effort,” she said.

Header Image: Western pond turtles are wrapped in special tape to keep them still and lined up in preparation for a CT scan to check for traces of shell disease. ©Katherine Haman