Share this article

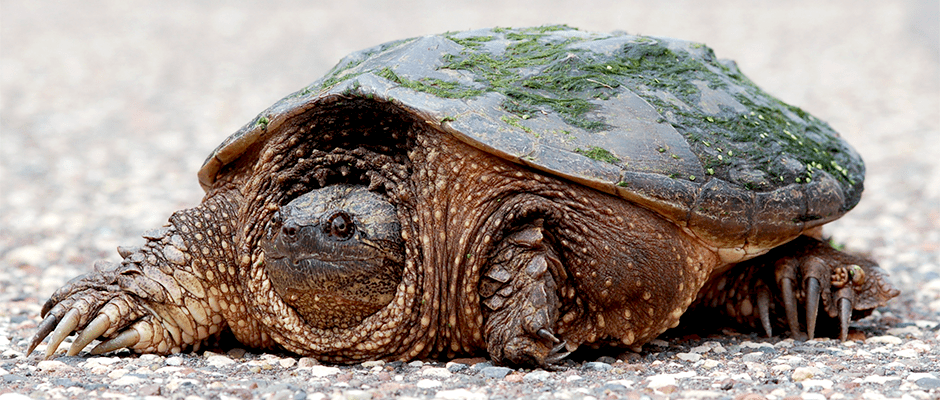

Ontarians debate snapping turtle hunting

In the growing debate over snapping turtle hunting in Ontario, a number of wildlife biologists and conservation groups are calling for an end to the practice.

Snapping turtles (Chelydra serpetina) are legally hunted in Ontario, and are also recognized as a species of “special concern” on the Species at Risk in Ontario List under the province’s Endangered Species Act and under the country’s Species at Risk Act. Special concern species are not considered threatened or endangered, but they are at risk of becoming threatened or endangered due to a combination of threats and life history traits.

In December 2016, Ontario’s Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry (MNRF) proposed a regulatory amendment under the Fish and Wildlife Conservation Act to reduce daily bag limits, possession limits, and season lengths for snapping turtle harvest. Currently, anyone with a valid provincial sport fishing license may bag up to two turtles per day and possess up to five turtles at one time. In several wildlife management units, the hunting season is year-round.

However, some biologists believe that a limit on harvest is not enough to sustainably manage the population—they believe that ending snapping turtle harvest is necessary to conserve Ontario’s population in the long-term.

On Jan. 30, the last day of the public comment period for the proposed amendment, a group of over two dozen conservation organizations—including Ontario Nature, the David Suzuki Foundation, and Earthroots—sent a letter to the MNRF’s Wildlife Section in strong opposition to the amendment. The group argues that allowing snapping turtle hunting to continue in Ontario is inconsistent with the objectives of last year’s proposed Management Plan for the Snapping Turtle (Chelydra serpentina) in Canada, published by Environment and Climate Change Canada. The management plan recommends six broad strategies for maintaining and increasing snapping turtle occupancy in Canada—one of which is to reduce the risk of mortality, injury, and harvesting.

Since snapping turtles in Canada often do not reach sexual maturity until 15 to 20 years of age, increases in adult mortality significantly impact the species’ regional survival. According to studies cited in the proposed management plan, “…high survival rates of adults (particularly females) are critical to the maintenance of turtle populations. An increase of just 2% or 3% in the adult mortality rate can result in a severe decline in the turtle population.”

The MNRF has not yet released a response or final decision on its proposed regulatory amendment since the public comment period ended on Jan. 30.

According to CBC News, Scott Gillingwater, a Species at Risk biologist with the Upper Thames Conservation Authority, said, “It sends a confusing message to the public to be able to hunt an animal that many people spend a lot of time and a lot of money to protect wetlands and protect these species, so it seems kind of in vain when these animals are lost due to a legal hunt.”

The Ontario Federation of Anglers and Hunters (OFAH) disagrees with the assessment that snapping turtles are at risk in Ontario. The organization generally supports the intent of last year’s proposed management plan, but it does not stand behind the proposed regulatory amendment or the calls for a ban on snapping turtle hunting. OFAH believes that there is a lack of empirical data on snapping turtle distribution and abundance in the province, and that restrictions on harvesting the turtles currently lack justification.

Hunting the turtles is prohibited due to science-based sustainability concerns in four out of the six Canadian provinces in which the species is found in the wild—Manitoba, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Quebec. Ontario and Saskatchewan are the only provinces that allow it.

In its Standing Position Statement on Hunting, The Wildlife Society endorses hunting as an appropriate means of managing wildlife populations when properly regulated following biological principles. Professional wildlife biologists are responsible for making management decisions in a scientific, sustainable, and socially acceptable manner.

Header Image: ©squamatologist