Share this article

For some species, keeping up with climate change may not be easy

Barriers could hinder some species from following their climate niches to new protected areas

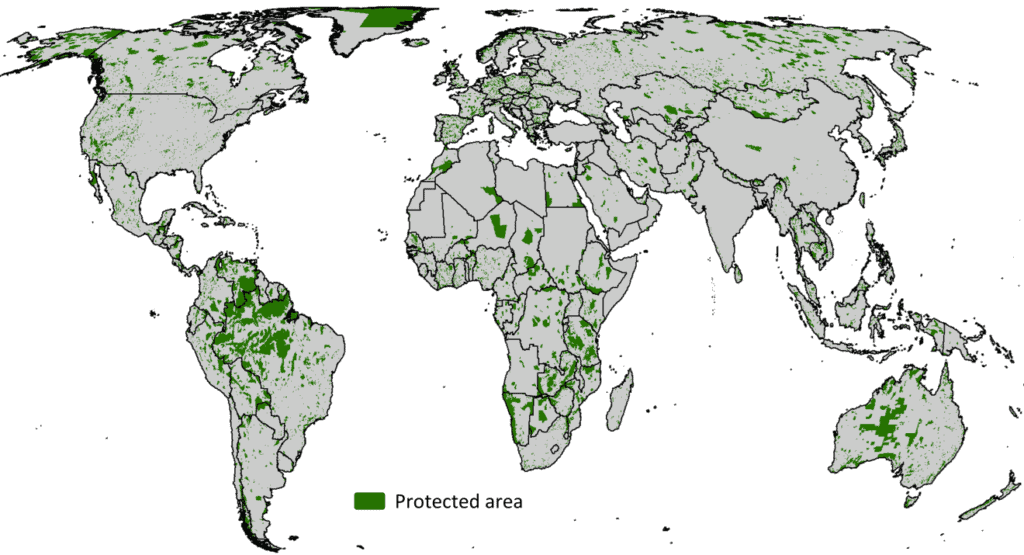

Protected areas are intended to safeguard a diversity of species in an increasingly human-dominated planet. As the climate changes, plants and animals may need to move to new protected areas that fit their needs. But getting to those areas may be challenging, researchers found.

Researchers previously looked at how unique climates in protected areas may be disappearing under a warming climate and, in some cases, are moving to different countries. Even for wildlife, international travel can be difficult.

“They have international borders to contend with, land use policies and cultural norms,” said Sean Parks, a research ecologist with the U.S. Forest Service’s Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute, who led the study.

But Parks and his team wanted to know how easily species could undergo climate-induced movement among protected areas. In a study published in Global Change Biology, they looked at the barriers species may face moving from one protected area to another to keep track with climate conditions.

“Species are generally expected to move upslope and poleward under climate change because climates are moving upslope and poleward,” Parks said. “The key assumption here is that species have certain climatic niches they’ve evolved with and are acclimated to, and they need to keep that through space and time.”

The researchers looked at four different factors that can impede climate induced movements from one protected area to another. One of the factors was the distance species need to travel, particularly for species that can’t disperse easily. Another factor was human land use between protected areas that can make travel difficult. A third was climate dissimilarities in between the protected areas. For example, if a species in the “sky islands” of the southwestern U.S. has to travel through the desert to get to another mountaintop, it has to endure a very different climate on their journey. Finally, they wanted to see if some climates might disappear altogether.

The researchers looked at current climates in protected areas and modeled where similar climates might occur in the future. That told them how far species may need to travel. They also looked at the areas in between to see what sorts of climates and human land use species would encounter on the move. “All of these factors are important,” Parks said.

They found that over half the protected areas across the planet exhibit climate connectivity failure, meaning that landscapes impeded species’ ability to move to suitable climates. “Protected areas are always going to help conserve biodiversity,” he said. “But at the same time, the amount and configuration of protected lands might not be sufficient for many species coping with climate change.”

Recent efforts to protect 30% of the world’s land by 2030 could reduce connectivity challenges, Parks said, but for some species, more protected areas may not be enough. For species with limited dispersal or tolerance for human land use, it may be necessary to consider sometimes controversial notions like assisted migration or colonization.

“It’s something we might want to think about a little bit more,” he said.

Header Image: Nahanni National Park Reserve, a protected area in Canada’s Northwest Territories, could provide habitats for wildlife pushed northward by climate change. Credit: Sean Parks