Share this article

For some songbirds, migration ends in a shark’s mouth

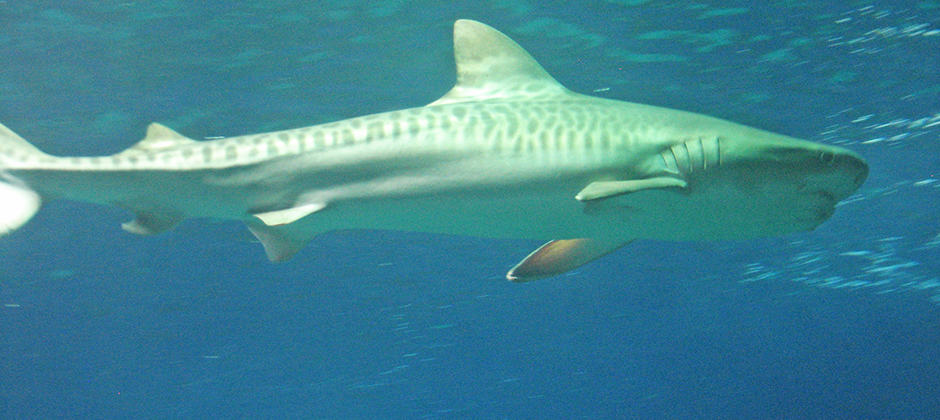

When Marcus Drymon was conducting his usual shark surveys in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010, he wasn’t surprised to catch a small tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvier). The surprise was what came along with the shark.

He brought it onto the boat to measure it, weigh it and release it. But as his team was taking the measurements, he said, the shark “barfed up” some brown feathers.

“It was pretty wild,” said Drymon, a fisheries ecologist and assistant professor at Mississippi State University who led a study published in Ecology that came from this first observation.

Scientists gather stomach contents from a young tiger shark using gastric lavage. ©David Hay Jone

After poring through bird identification books and failing to identify the feathers, Drymon sent the feathers to his colleague Kevin Feldheim at Chicago’s Field Museum. Feldheim performed a DNA analysis and determined the bird was a brown thrasher (Toxostoma rufum) — a migratory songbird more associated with scrubby hedgerows than open water. “I was not expecting that at all,” Drymon said.

But after looking back through the literature, Drymon found similar anecdotal accounts dating as far back as the late 1940s. “We wondered how much this is occurring,” he said. “Is this just one random, one-off shark encounter with a small bird? Or is this happening with some regularity?”

Over the next eight years, Drymon and his colleagues sampled stomach contents from 100 tiger sharks. If they caught a dead shark, they removed its stomach and went through the contents. If it was alive, they performed a gastric lavage, inserting a PVC tube with a hose down the shark’s mouth, rinsing the stomach, turning the shark upside down and releasing its stomach contents.

Around 40 of the sharks they examined had consumed birds — 11 different species of them. But what surprised researchers most was the type of birds they discovered. These weren’t seabirds. They were species such as barn swallows (Hirundo rustica), eastern kingbirds (Tyrannus tyrannus), house wrens (Troglodytes aedon) and common yellowthroats (Geothlypis trichas).

“Of all 11 species, none of them were pelicans or marine birds,” Drymon said. “They were all terrestrial birds — not at all what we expected to see in a tiger shark stomach.”

These songbird feathers were removed from the contents of a young tiger shark’s stomach. ©Marcus Drymon

He and his colleagues wanted to figure out how this was happening. Using eBird, they plotted the peak sightings in the area for the 11 species. It became clear that interactions between tiger sharks the species were occurring in the fall during these peak sightings, when many neotropical migratory birds leave North America for Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula.

“This was a strong suggestion that these interactions were tied to migration,” he said.

But what really puzzled the team was that this wasn’t happening during the tail end of the birds’ migration when they may be exhausted and fall into the water. Instead, it was right when they were starting migration.

“Digging more, we found these strong weather events, like cold fronts and tropical storms,” he said. These were likely causing thousands of the 2 billion migratory birds taking wing in the autumn to plunge into the water, the team concluded. At the same time of year, tiger shark abundance in the Gulf was at its peak — three times higher than any other time.

Drymon suspects tiger shark mothers are using this area as a nursery since it’s a productive area, where there’s ample food sources for their first year of life.

Header Image: Tiger sharks are consuming terrestrial birds while they are migrating over the Gulf of Mexico. ©Gord Webster