Share this article

Can genetics offer new tools for wildlife biologists?

Could genetic advances in the laboratory transform wildlife management on the ground?

It’s a question APHIS Wildlife Services biologists are asking as they look at adopting genetic technologies increasingly being used in medicine to the field of wildlife biology.

“We’re on the tail end of this wave in terms of wildlife applications,” said Larry Clark, director of Wildlife Services’ National Wildlife Research Center in Fort Collins, Colorado. Medical and industrial applications are farther ahead, but some of these emerging technologies, like gene editing, gene drives and gene silencing, could hold promise for wildlife management.

“The things we, universities and other collaborators are working on were once science fiction.Fifty years from now, the things that are on the horizon,the things we’re investigating from a science perspective, will probably be much more commonplace,” Clark said.

The science behind these technologies is complex, but getting social acceptance of some of these techniques may prove even trickier. Genetic technologies could hold promise for conserving wildlife and reducing threats, he said, but before they can be deployed, society has to weigh their potential benefits and consequences, and government needs to create appropriate regulation.

It’s a topic Wildlife Services biologists plan to address at a symposium, Current and Future Genetic Technologies for Wildlife Management, scheduled for the TWS Annual Conference in Cleveland, Ohio, which takes place Oct. 7 to 11.

“We have been editing genes since we started agriculture thousands of years ago,” Clark said, “but we did it in a black box with selective breeding.

Now, gene editing tools like CRISPR allow biologists to insert or remove DNA to achieve specific traits. Could bats be engineered for resistance to white-nose syndrome, which has wiped out entire colonies as the disease spreads across North America? Could amphibians be made resistant to fungal diseases that have contributed to their global decline?

It’s possible, Clark said. “With genomics, we now have the keys to editing almost anything. We understand the system, in principle. In practicality, there are a lot of details.”

Gene drives are a genetic technique that could be useful in wildlife management. They allow scientists to select a specific trait, genetically engineer individuals in the laboratory to express that trait, and then encourage the propagation of that trait in the wild by releasing the individuals.

Such selection could be particularly useful for controlling invasive species, Clark said. For instance, on islands where invasive mice have taken over, scientists are exploring the concept of engineered mice to gradually reduce the invasive wild mice population. Engineered mice that could potentially produce only male offspring would be allowed to breed with the wild mice. Eventually, only male mice would exist, and as a consequence the invasive population would die out. Scientists are currently modeling such scenarios.

The technique could also be used to boost struggling populations. Could disease-resistant birds be introduced in Hawaii to help make their populations less vulnerable to avian malaria?

“It’s important to note that such gene editing approaches are not happening today or tomorrow,” Clark said. “We’re years away. And a lot of people have some very legitimate concerns.”

Gene silencing technologies may be closer to becoming reality. These technologies use genomics to target specific expressions of a species’ proteins and apply interfering RNAs to disrupt them. The approach could allow for species-specific toxicants, Clark said. Instead of putting out a trap or a pesticide which could impact non-target species a species-specific toxicant could be created that would only affect, say, feral swine (Sus scrofa) without threatening other animals that might eat it or scavenge an affected carcass.

“͞The science is the easiest part of this,” Clark said. “The social atmosphere is our biggest challenge. You can do all the science you want but unless you have buy-in from the stakeholders and the community, nothing is going to succeed.”

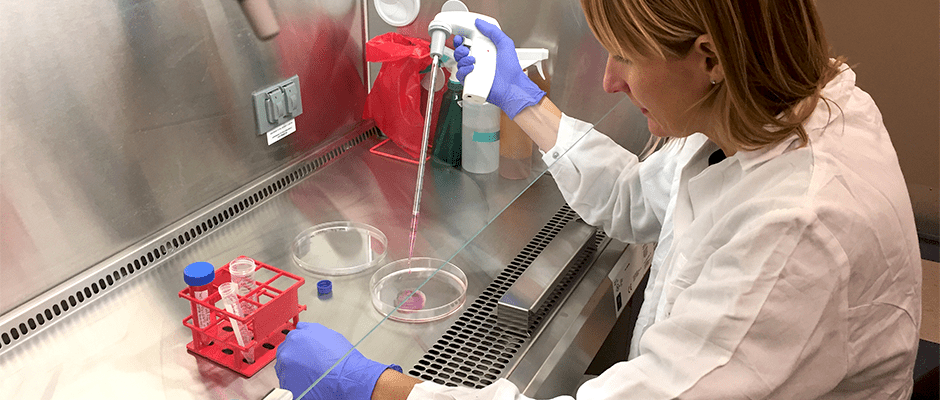

Header Image: Genetic technologies could present new opportunities to wildlife professionals, but they bring with them some difficult questions about how these technologies should be used. ©Gail Keirn, USDA-APHIS