Share this article

Birds breed better when they ‘float’ through bad times

Many bird populations include perplexing young males who choose not to settle down and breed. Instead, they “float” through the breeding season without a territory. But this unattached approach may benefit birds in tough times.

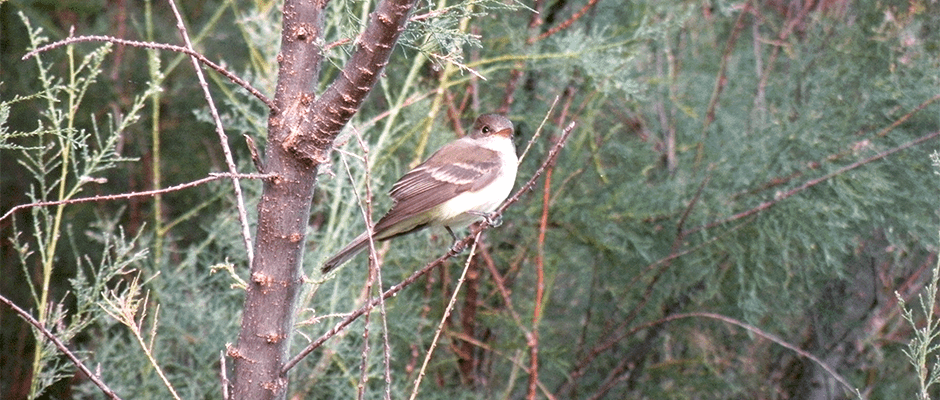

Biologists examining imperiled southwestern willow flycatchers (Empidonax traillii extimus) in Arizona recently found that these “floaters” survive and reproduce more than breeding birds in the aftermath of major drought.

“Floaters tend to move around not showing territorial behaviors, so they’re hard to study,” said Tad Theimer, lead author on the paper published in The Auk: Ornithological Advances. “We were setting up nets throughout the year and would catch these birds we never saw acting territorially, so we knew they were in the habitat but weren’t breeding. That gave us the opportunity to get a window on this little-known secretive ‘underworld’ of bird society.”

Listed as endangered in 1995, southwestern willow flycatchers inhabit rare riverine forests that are disappearing due to activities like damming and farming. In a cooperative study between the Bureau of Reclamation, U.S. Geological Survey and Arizona Game and Fish Department, researchers set up study areas near central Arizona’s Roosevelt Reservoir and the San Pedro and Gila rivers, where they caught 1,000 flycatchers that had been marked previously with colored bands. They analyzed the birds’ survival and reproduction from 2001 to 2004, including a 2002 drought that took a toll on their insect prey.

Their goal was to gain some insight into how floaters functioned in this population. Some scientists believe floaters are weak individuals unsuccessfully flitting around in search of a vacant spot. Others believe they eventually become prolific breeders, waiting near optimal breeding spaces that are occupied and nabbing them when they become available in later years.

A biology professor at Northern Arizona University, Theimer and his colleagues found the drought produced an unusually high number of floaters, and their survival and reproductive success were higher in the following years than those of the original breeding birds.

“In most years, if you’re a floater, you lose out on reproduction and don’t survive as well,” he said. “We found this interesting flip in the face of this extreme climatic event.”

The number of floaters nosedived the following year as the flycatchers seized empty breeding areas, but it was the ex-floaters that reproduced most successfully.

Floaters help populations persist through environmental challenges, Theimer said. “If you lose breeders, floaters quickly take territories over and produce young. Higher survival by birds that floated during the drought allowed them to fill open spaces created by that low reproduction year, so you didn’t see a fall in productivity.”

In this way, he said, floaters could help bird populations weather, to some extent, the higher frequency of environmental extremities wrought by climate change.

“The floater population becomes an important indicator of overall population health,” Theimer said. “If there’s not many floaters, they’re not going to be able to see themselves through climatic stressors. But if you start piling these extreme events up one after the other, we’ll be tapping out the ability of floaters to maintain populations through these crunch periods.”