Share this article

Honey bees pollinate a lot more than just crops

Buzz about the agricultural significance of honey bees and concerns about the implications of their decline for food production are widespread, but discussions about their status as pollinators beyond farms are rare. Yet by quantifying the insects’ prevalence in natural ecosystems around the world, scientists recently showed that honey bees also come out on top in the pollination of wild plants.

“They’re perhaps one of the most impactful pollinators in natural settings because they’re found in more places than any other pollinator species,” said Keng-Lou James Hung, lead author on the paper published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B. “They’re the most widely distributed pollinator, they’re abundant in many systems, they’re able to visit a large diversity of plant species — most whose flowers their bodies fit into — and they’re active for long seasons — even year-round in many ecosystems.”

While a doctoral candidate at the University of California, San Diego, Hung became curious about the dominant numbers of the western honey bee (Apis mellifera) despite the great diversity of other bee species he noticed in local natural reserves. To figure out whether this pattern held throughout natural landscapes globally, from 2014 to 2016, he and his colleagues examined honey bees’ contributions to 80 interaction networks of wild pollinators and plants across the six inhabited continents and several islands. They compiled biologists’ observations on how often honey bees and thousands of other pollinators contacted and potentially pollinated flowers.

“On average, honey bees attained one out of every eight visits documented in these networks,” Hung said, racking up more trips to flowers than any other pollinator.

“The honey bee is probably the most successful pollinator in the world at present, so we need to be aware of not confusing the health of managed honey bees and the conservation status of this bee,” he said. “Honey bees appear to be thriving in many natural ecosystems.”

Although some wild honey bee populations have succumbed to pathogens, Hung said, “as a species, they seem fine,” especially in warm areas in Hawaii, Central and South America and Australia.

First introduced to North America by European settlers to produce honey, honey bees are now so plentiful here, Hung said, that they could be negatively affecting native pollinators and plants. In California, studies have shown that honey bee colonies can outcompete nearby bumble bee (Bombus spp.) colonies.

Despite all the pollinating that honey bees do, they’re hardly alone. Most pollination is still carried out by other pollinators, Hung said, “so it is absolutely crucial to continue conservation efforts of non-honey-bee pollinators worldwide, even in places dominated by honey bees.”

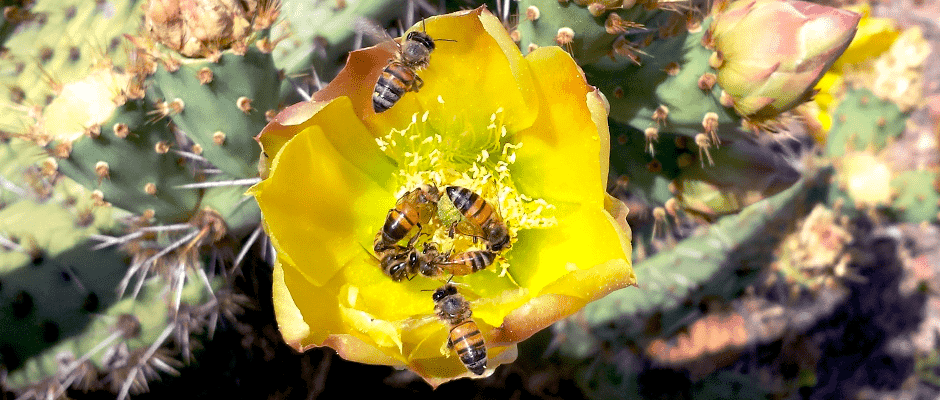

Header Image: Non-native honey bees crowd a flower of the native coast prickly pear cactus in Southern California. ©Keng-Lou James Hung