Share this article

Wild Cam: Species shift active time in cities

For urban wildlife, adapting to city life means changing the times of day when they would usually be active in more natural settings.

“In order for species to function within novel ecosystems, we know some behavioral change has to occur,” said Austin Green, a researcher with the Science Research Initiative at the University of Utah. “How that can occur can be different across species.”

In a study Green led published in Global Ecology and Conservation, he and his colleagues, with help from hundreds of citizen scientists, deployed camera traps in both urban and wild areas in Utah, from downtown Salt Lake City to protected natural areas. Thanks to volunteers with the community science program Wasatch Wildlife Watch, they were able to deploy 350 camera traps.

The team detected about 20 different mammal species in the camera trap photos, some that surprised them. They gathered hundreds of photos of mountain lions (Puma concolor) and logged the first verified detection of a wolverine (Gulo gulo) in Utah, which biologists later captured.

Enlarge

Credit: Wasatch Wildlife Watch

The species that showed up most in all of the areas they studied were mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus), rock squirrels (Spermophilus variegatus), coyotes (Canis latrans), striped skunks (Mephitis mephitis) and northern raccoons (Procyon lotor). The team compared behaviors of these species in urban versus more wild areas.

Raccoons and skunks seemed to adapt seamlessly to urban life. “There were no behavioral changes at all,” he said.

Enlarge

Credit: Wasatch Wildlife Watch

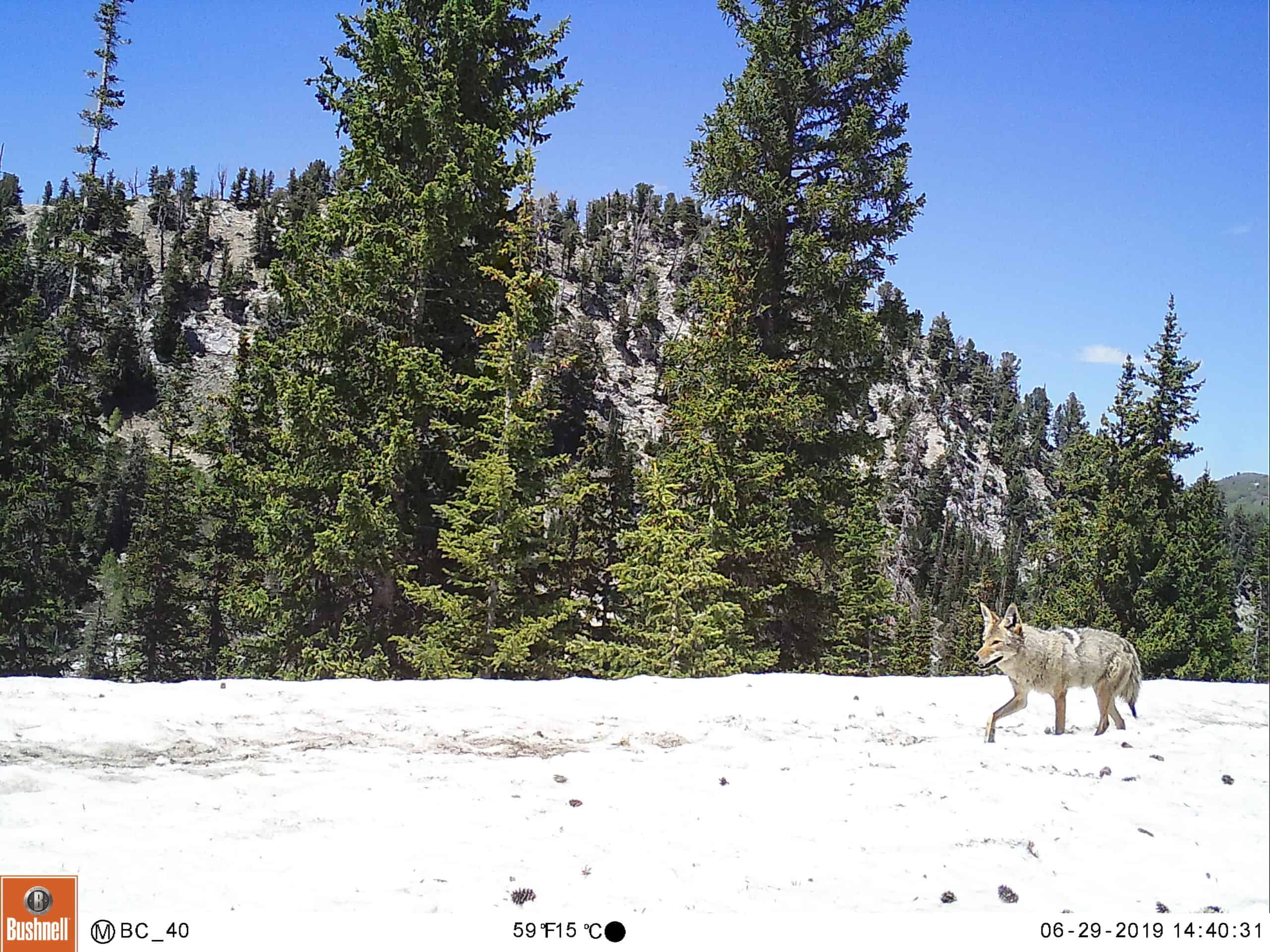

But the other three species underwent drastic changes in urban environments. Coyotes became more nocturnal in developed areas, when human activity was the lowest. They think that’s because coyotes are persecuted by humans in the Salt Lake City area and are actively trying to avoid them.

Enlarge

Credit: Wasatch Wildlife Watch

Rock squirrels and mule deer, on the other hand, became more diurnal. “They were more active when people were active,” he said.

Green said their changes in activity patterns, especially for mule deer, may have to do with them avoiding coyote predation. Previous research shows that coyotes prey on deer fawns while the fawns are being raised. “It seems to be a direct response that in order to raise their young, deer are actively avoiding predation pressure from coyotes,” he said.

Enlarge

Credit: Wasatch Wildlife Watch

Green said more research needs to be done on how this could impact the workings of the entire ecosystem. He also hopes to research further if this is only occurring during fawning season.

And even though deer and squirrels may be avoiding the dangers of the night life, being active at the same time as humans can cause problems, too. “It’s a catch-22,” he said. “They deal with all of the risks of living in a human environment. That includes vehicle strikes or other human-caused mortality or injury.

Enlarge

Credit: Wasatch Wildlife Watch

More research about this and other topics is important, Green said, as urban growth continues.

“It’s important to understand how these ecosystems function and what type of factors within a city lead to better human-wildlife coexistence,” he said.

Header Image: Coyotes living in cities shift their active time to nighttime. Credit Wasatch Wildlife Watch