Share this article

Wild Cam: Habitat restoration not enough to protect caribou

Across the landscape of British Columbia and Alberta stretch hundreds of thousands of kilometers of seismic lines — strips of land cleared to test for oil and gas resources underground.

While recent techniques leave less disturbance, seismic lines from the 1980s and ’90s remain, some with attempts at revegetating them and some not. These lines can have significant impacts on populations of woodland caribou in the region — a species that is declining throughout Canada.

Recent research suggests that efforts to restore these seismic lines may not be enough to protect the caribou. In a study published in Biological Conservation, researchers found these restoration efforts had little effect on caribou and other wildlife.

Researchers found that wolves showed a preference for unrestored seismic lines but weren’t discouraged from using restored lines. ©UBC Faculty of Forestry

“This is boreal forest,” said lead author Erin Tattersall, who completed the research as a master’s student at the University of British Columbia. “It’s very boggy. There are a lot of wetlands. It regenerates really, really slowly.”

A black bear appears on a restored seismic line. ©UBC Faculty of Forestry

Revegetation needs to be done, Tattersall said, but in the short term, it isn’t enough to help restore woodland caribou.

“We are in kind of a caribou emergency,” she said. “If we want to keep these animals on the landscape, we need to think about what other strategies we can use, as well as habitat restoration.”

Only white-tailed deer — a key caribou competitor — showed less use of restored lines. ©UBC Faculty of Forestry

Tattersall’s team set up camera traps along seismic lines and found little difference in wildlife use between those that had been restored and those that hadn’t. The researchers were interested in not just how woodland caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou) used these landscapes. They also wanted to see how predators like gray wolves (Canis lupus) and black bears (Ursus americanus) and other prey, like white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) and moose (Alces alces), were affected. Did replanting the lines help separate caribou from predators and competing prey?

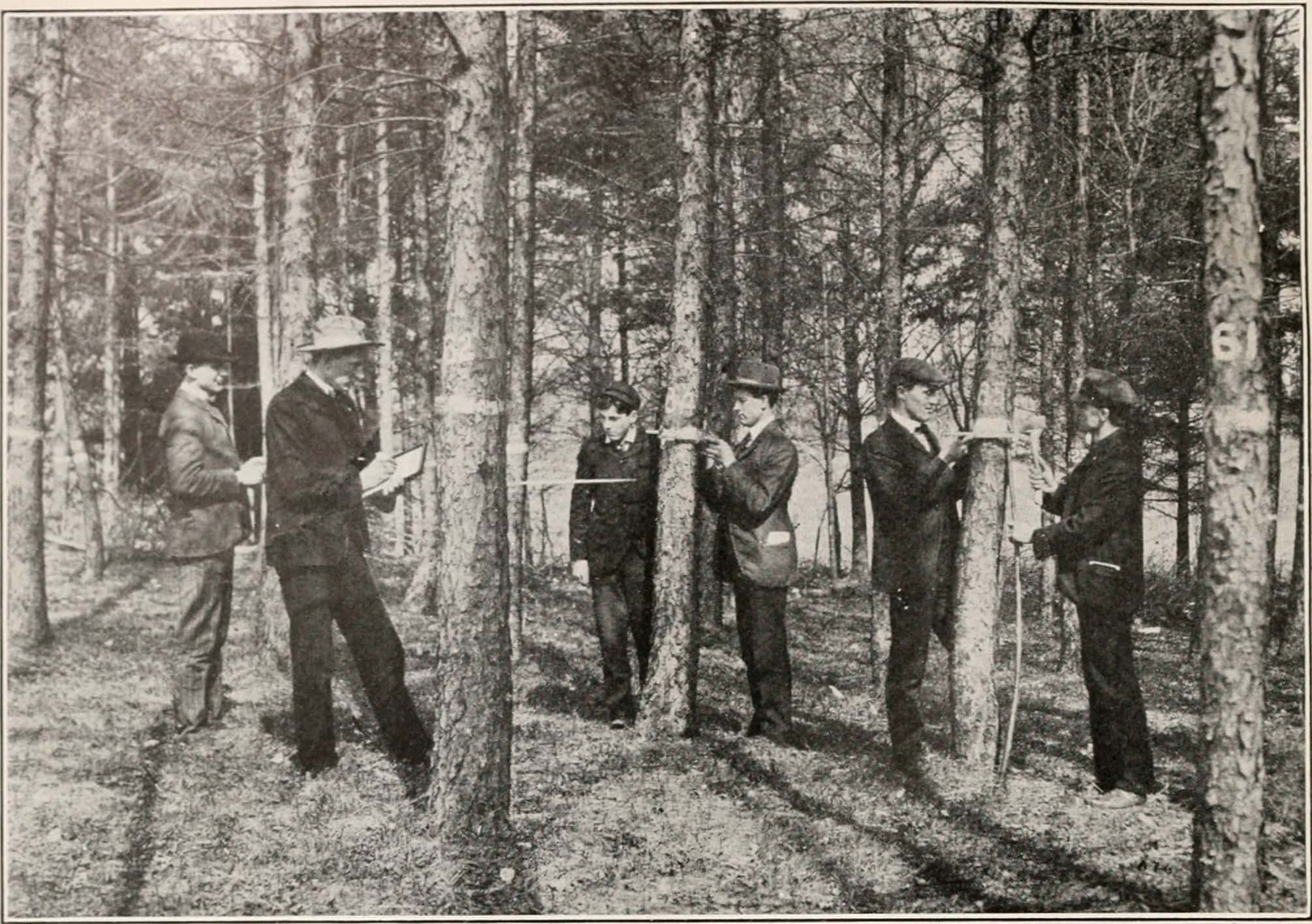

Researchers set up 60 camera traps in northeastern Alberta. ©UBC Faculty of Forestry

They found that three to six years after restoration, predators used restored and unrestored lines about equally. Only white-tailed deer — a key competitor — showed less use of restored lines.

Camera traps picked up other species, including this Canada lynx (Lynx canadensis) appearing to strike a pose. ©UBC Faculty of Forestry

“I think the biggest takeaway is that you can’t assume that the restoration you’re doing is going to work,” Tattersall said. “You’ve got to validate that assumption. You have to have a clear objective of what the restoration is supposed to do and continue to monitor that.”

The study also points to the importance of looking at multiple species, even if only one species is the focus of conservation issues, she said.

Lead author Erin Tattersall performed the research as a master’s student at the University of British Columbia. ©UBC Faculty of Forestry

“I also think it provides a good baseline,” she said. “so maybe this restoration isn’t doing what we want it to in the short term. So how can we improve upon that? How can we make this type of restoration a little bit better? Are there other things we can incorporate? Are there things that we should do differently?”

Placing movement barriers along the lines may be one method, Tattersall said, making it harder for predators to travel across the caribou range on seismic lines that still have not revegetated.

This photo essay is part of an occasional series from The Wildlife Society featuring photos and video images of wildlife taken with camera traps and other equipment. Check out other entries in the series here. If you’re working on an interesting camera trap research project or one that has a series of good photos you’d like to share, email David at dfreywildlife.org.

Header Image: Research suggests restoring habitat may not be enough to save threatened woodland caribou — an iconic animal that's a major part of boreal forests in North America and a key part of the culture and economy of many Indigenous peoples in Canada. ©UBC Faculty of Forestry