Share this article

Uncovering urban snake removal patterns

When it comes to snakes, Bryan Hughes is full of helpful advice. His Facebook and blog contains everything from recommendations on how to unstick a snake from a glue trap to where to watch out for rattlesnakes — supposedly they even hide in Christmas decorations. He cautions people against releasing kingsnakes to control rattlesnakes and gives pointers on identifying venomous snakes versus relatively harmless reptiles.

Now, researchers are digging into the data he collected on more than 2,000 total removals in the greater Phoenix area in 2018 and 2019 to get a better understanding of human-wildlife conflict and urban snake dispersal.

Western diamond-backed rattlesnakes, such as the one caught in a rat trap here, were the most commonly removed snakes in the Phoenix area. Credit: Bryan Hughes

“We were just blown away by the dataset,” said Heather Bateman, an associate professor at the Arizona State University and the lead author of a study published recently in Global Ecology and Conservation. The collection included more snakes than all the ones recorded in the same area, during a 10-year period on iNaturalist, a popular community science reporting app where people can take photos to report species.

Hughes’ business, called Rattlesnake Solutions, is the one residents call when they have a snake they want removed from their yard. In theory, it’s a service meant safely remove venomous snakes — there are six that occur in the greater Phoenix area. But since people can’t tell the difference between these snakes and others that pose less danger to humans, Rattlesnake Solutions often ends up removing all kinds of species.

Hughes and his employees record the species, and time and place of capture, for all snakes they remove — information he provided to Bateman and her colleagues. The researchers then paired this with other social ecological data — data collected long-term about residents’ perceptions of snakes — in an effort to learn more about urban snake populations and their interactions with humans.

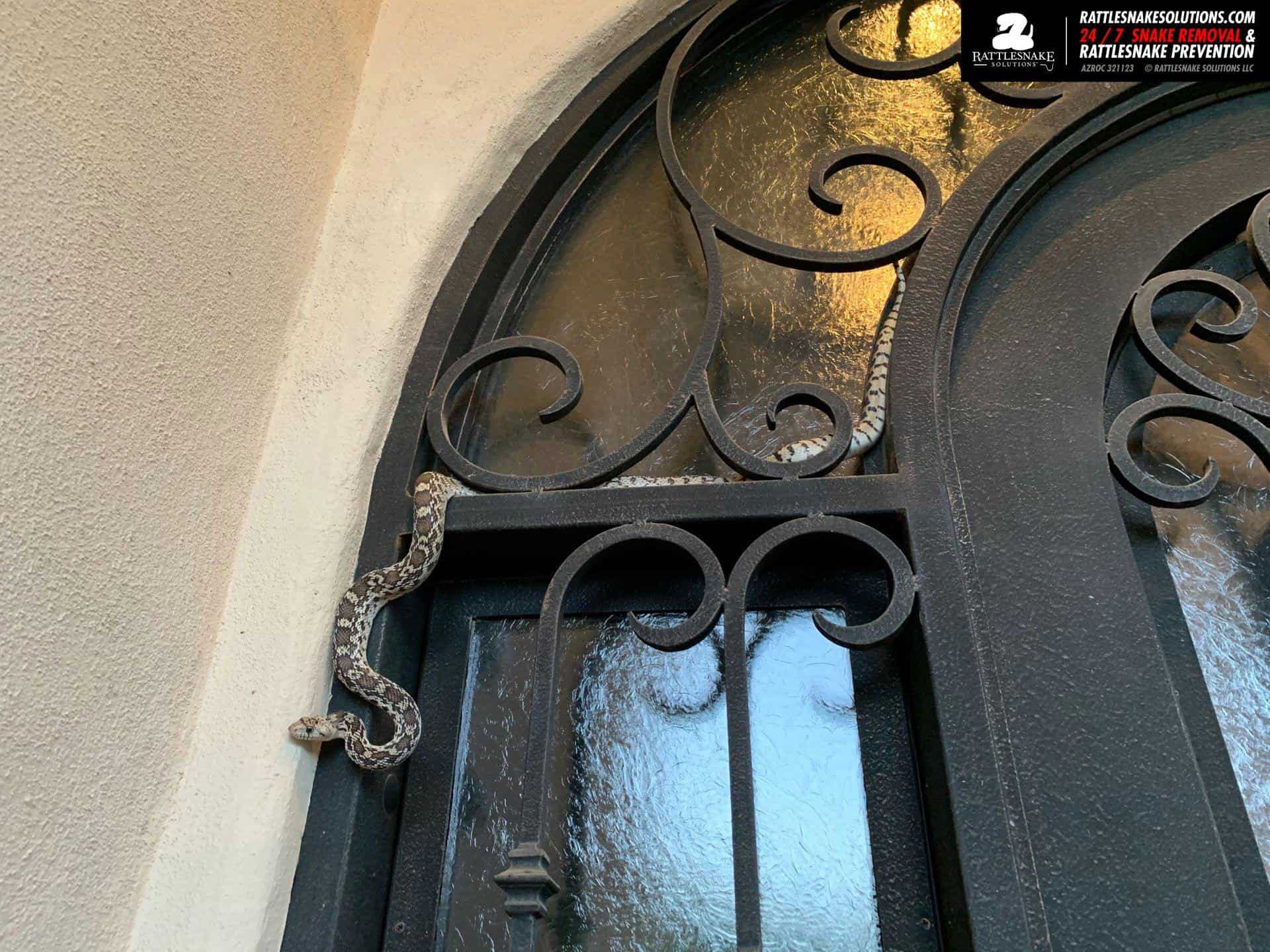

Gopher snakes were the second most commonly removed snakes in the Phoenix area. Credit: Bryan Hughes

When they examined the data, they found that 68% of all snakes removed were western diamond-backed rattlesnakes (Crotalus atrox). But Hughes’ team also removed five other species of venomous snakes: southwestern speckled rattlesnakes (Crotalus pyrrhus), black-tailed rattlesnakes (Crotalus molossus), Mojave rattlesnakes (Crotalus scutulatus), tiger rattlesnakes (Crotalus tigris) and sidewinders (Crotalus cerastes).

The most common non-venomous snakes they removed were Sonoran gophersnakes (Pituophis catenifer). In fact, these were the second most common snakes removed altogether, accounting for 16% of all removals in the dataset. Co-author Jeffrey Brown, a postdoctoral researcher at ASU, said that the relatively large size of gopher snakes is probably part of the reason people inquired to have them removed so much.

“I think [their large size] ties into people’s perception of fear,” he said.

But 83% of people called Rattlesnake Solutions because they believed the snakes near their homes were venomous — a number that didn’t correlate with the percentage that actually were venomous.

“People might be taking this move unnecessarily,” Brown said.

But gopher snakes, as well as California kingsnakes (Lampropeltis californiae), are also some of the ones that seem best adapted to denser urban areas.

The data also showed the areas where people lived and how much money they make mattered when it came to snake removal. This likely relates to the inequity of nature that exists in the city. More affluent areas tend to be more on the outskirts of town, or in areas near parks or nature preserves ideal for snakes. As a result, urban biodiversity is unevenly spread through the city. People living in homes closer to wild areas are more likely to get more snake visits.

“A lot of wealthier neighborhoods are also adjacent to desert preserves where there are a lot of snakes,” Brown said.

More affluent people also have more money to pay for a snake removal service than those living in poorer neighborhoods. People with less disposable funds may take matters into their own hands, avoiding snakes or removing snakes themselves. It’s also possible that people in rich or poor areas may simply kill snakes on their property — the database didn’t have this kind of information.

A Western diamond-backed rattlesnake. Credit Bryan Hughes

“The removal of snakes doesn’t necessarily relate to where snakes always are,” Brown said.

The researchers also found that removals were more likely to come from neighborhoods with high income but fewer snake removal calls came from high income areas with high education levels. Brown speculated that this might be due to those people having more ecological knowledge.

While Hughes’ database also reported a few removals of non-native species like pythons, likely the result of escaped pets, most of the native snakes his team removed from homes were released in native settings if they seemed healthy and fit.

“Brian is really passionate about snake conservation,” Bateman said.

Brown added that better information could help reduce the number of non-venomous snakes removed from people’s properties unnecessarily. “But people will always be afraid of snakes,” he added.

Bateman said that the study also highlights how much researchers can learn by working with private wildlife businesses. Hughes is a wealth of information about how people might modify their shrubs to make them less suitable for serpents, for example — information even researchers may not even have.

Header Image:

Southwestern speckled rattlesnakes are among those removed from around homes in Arizona.

Credit: Bryan Hughes