Share this article

The varroa mite invasion and its aftermath

Many investors will remember 1987 as the year the stock market fell nearly 23 percent in a single day. The crash was so sudden and precipitous that it is forever known as “Black Monday.” Few people are aware of a more insidious event that happened that year, but for most U.S. beekeepers 1987 is remembered as the year of the varroa mite invasion. And beekeeping has not been the same since.

Soon after the initial invasion, reports of catastrophic colony failures were occurring across the country. The speed of the infestation of this Asian parasite caught most U.S. beekeepers off guard, even though most were aware that Europeans had been struggling with their own varroa invasion since the 1970s. Within a decade after the U.S. introduction, varroa mites were reported to be in all 50 states.

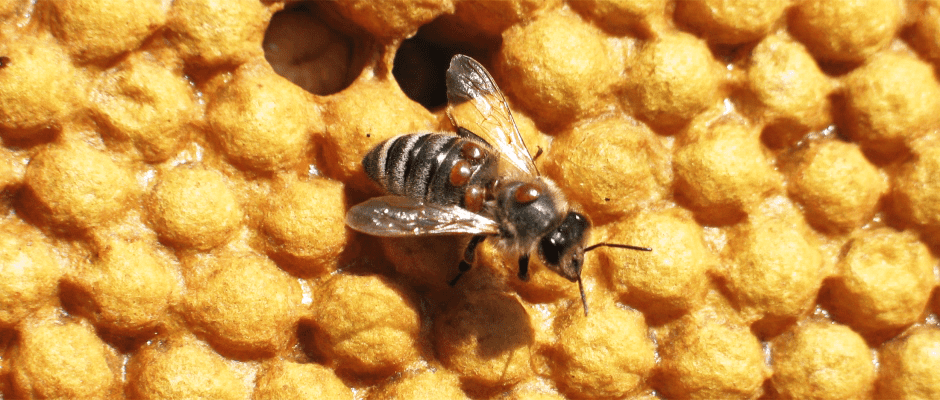

Varroa destructor is an apt name for this pest. Viewed under high magnification, the varroa mite resembles a flattened armored tank, with grappling legs and mouthparts designed to pierce the bee’s exoskeleton in order to suck its host’s hemolymph, a circulatory fluid similar to blood. The mouthparts in male mites are not robust enough to penetrate adult bees and so males are confined to the brood cells, where they feed on immature bees, and die soon after bee brood reaches maturity and emerges as adults.

Direct feeding on the hemolymph can weaken the host’s immune system and shorten the bee’s life span, but the varroa mite goes one step further by transmitting deadly viral diseases as it feeds. Bee experts have compared varroa’s feeding activity to a dirty hypodermic needle, which is why it is considered to be the most destructive pest of honey bees and a major cause of colony failure. Colonies carrying high varroa infestations in the fall are especially vulnerable and are unlikely to survive the winter.

Managing varroa has made beekeeping more difficult than ever before. Unlike the Asian honey bee (Apis cerana), the western honey bee (Apis mellifera) has few natural defenses against this invasive parasite. Beekeepers use cultural practices and chemical control to help keep infestation levels down, but mites can easily re-enter relatively clean colonies during the growing season and are notorious for developing resistance to the few in-hive chemical treatments that are commercially available.

To say that everything changed for beekeepers after varroa is no understatement. Worldwide, this pest is estimated to have killed hundreds of thousands of colonies, resulting in billions of dollars of economic loss. For beekeepers that already operate on a tight budget, varroa has led to higher production costs and lower profit margins. Some note that they now must work twice as hard to produce half the result.

Fortunately, there is hope. Academia, industry, government, and others are working collaboratively to improve the health of bees. Last year, the Honey Bee Health Coalition published its Varroa Management Guide, which provides beekeepers with practical tips for monitoring and controlling this pest. Increasing our knowledge base, coupled with targeted research and a commitment to comprehensive management practices are the best ways to ensure the devastation caused by varroa becomes a thing of the past.

For more information go to: https://beecare.bayer.com/bilder/pdf/The_Varroa_Mite.pdf