Share this article

Pruitt signs ‘Secret Science’ rule, controversy remains

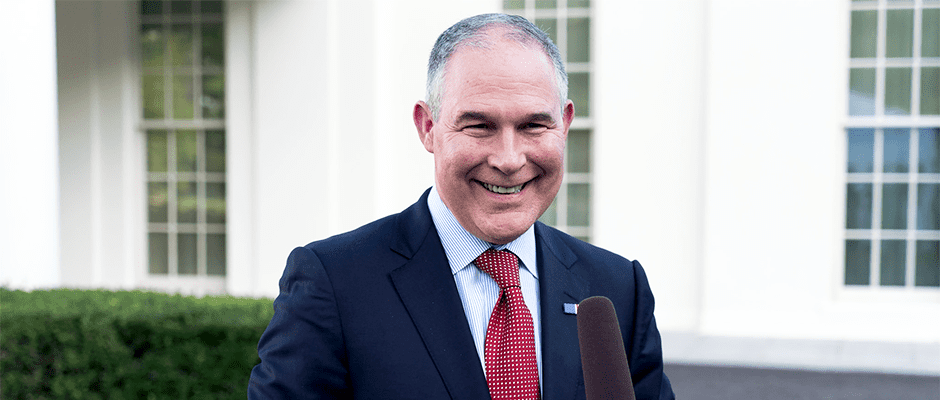

Environmental Protection Agency Administrator, Scott Pruitt, wants to promote the “ability to test, authenticate, and reproduce scientific findings” that the agency uses in its rulemaking process with the proposed rule he signed on April 24.

The Strengthening Transparency in Regulatory Science rule has been dubbed the ‘Secret Science’ rule because Pruitt has stated it will bring an end to “the era of secret science” he believes has driven the agency to create regulations based on political agendas rather than scientific justification. The rule would require the EPA to ensure data behind scientific studies the agency uses for developing regulations are publicly available, enabling independent review. The proposal says this would be consistent with the data access requirements of some scientific journals, such as Science and Nature.

Rep. Lamar Smith, R-Texas, chairman of the U.S. House Science, Space, and Technology Committee, praised Pruitt for the rule change. Smith has sponsored several pieces of legislation that would have effects similar to the proposed rule, most recently the HONEST Act (H.R. 1430), which passed the House but stalled in the Senate in March 2017. The Congressional Budget Office reviewed the Secret Science Reform Act of 2015 (H.R. 1030), another of Smith’s bills, and determined that the EPA would spend $250 million per year for the first few years to ensure data from every study the agency relied on was made public; alternatively, the EPA could rely on fewer studies every year, which would reduce costs but potentially undermine the quality of the agency’s work.

The nearly 1,000 scientists who signed a letter to Pruitt agree that there are issues of transparency and reproducibility that should be addressed within the scientific community, but that this rule does not actually address those problems. Instead, they see this rule as an effort to “weaponize” scientific language for political ends. The letter highlights that many of the public health studies used by the EPA are based on one-time events that could not, and should not, be replicated, such as 2010 the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. The rule could also affect the intellectual property or proprietary rights of scientists gathering the data, according to the letter.

In an op-ed for The New York Times, Gina McCarthy and Janet McCabe, former EPA officials, point out that in order to be published, studies have to pass the rigors of scientific-peer review. Additionally, some influential studies use confidential medical information, so releasing the data could potentially create privacy concerns or incur significant costs to protect private information before data could be released.

Other critics worry that raw data could be cited out of context by industries and used to influence controversial regulations.

Sen. Tom Carper, D-Delaware, ranking member of the Senate’s Environment and Public Working Committee, wrote a letter to Pruitt on April 24 requesting clarification on matters including how the EPA would base regulations on the best available science if large portions of scientific literature were excluded because of the public data requirements and why a rigorous peer-review process is not a sufficient basis for agency policy.

Additionally, more than 60 House Democrats wrote to Pruitt requesting the public comment period be extended to 90 days rather than the current 30. Considering the significant responses from scientists before the rule was released, the representatives do not believe that the minimum of 30 days will not allow enough time to gather feedback from stakeholders, particularly for such a big change.

Currently, the proposed rule is open for public comment until May 30.

Header Image: EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt was often an opponent of the agency’s environmental protections during his time as the Attorney General of Oklahoma. ©The White House