Share this article

Plucking hairs: New feral swine genetic archive

Tucked away in the National Wildlife Research Center’s (NWRC) genetics laboratory, biologist Dr. Tim Smyser opens a box from USDA Wildlife Services field specialists in Florida. It could have come from Wildlife Services experts in any one of 39 states and Guam who are part of a national effort to create a feral swine genetic archive. Inside the box are hair samples from feral swine. Comprised of at least 30 hairs each, the samples provide NWRC geneticists with enough DNA to genotype or “genetically fingerprint” individual feral swine. While they may not seem like much, these hairs will help scientists identify and distinguish among current feral swine populations as well as determine their origins.

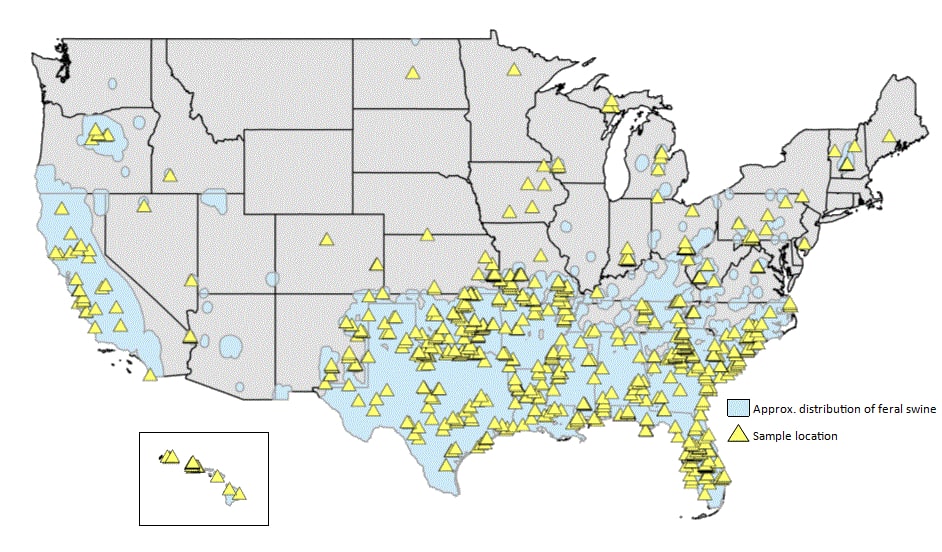

Map showing feral swine genetic sampling locations. Wildlife Services experts partner with federal, state, and local agencies across the country to manage feral swine damage. ©USDA Wildlife Services

To date, more than 5,400 samples have been collected by Wildlife Services biologists and field specialists, with 75 percent within the past two years. NWRC geneticists expect samples from Canada and Mexico to be added to the archive later this year.

Samples are collected opportunistically as part of operational efforts to control feral swine damage. Hair is plucked from the back of the animal.

Analysis so far has revealed nine distinct genetic populations in the United States associated with 1) southeastern states, 2) south central states, 3) Great Smoky Mountains National Park, 4) North Carolina and Virginia, 5) southcentral Indiana, 6) west central Illinois, 7) Oahu, 8) Kauai, and 9) northwest Arizona. Geneticists are also beginning to compare the genetics of emerging feral swine populations with potential source populations (including domestic breeds and wild boar) to help identify the origins of new populations. For instance, did an emerging feral swine population in Michigan originate from Texas or Canada? The answer may help guide future management actions, policies or regulations.

As part of USDA Wildlife Services’ feral swine operational and disease surveillance efforts, its biologists collect feral swine hair samples for the genetic archive. ©USDA Wildlife Services

As the genetic archive continues to grow, NWRC experts will soon have the necessary sample sizes to address questions about local or regional processes that influence feral swine expansion and their impacts on native ecosystems.

The NWRC welcomes inquiries about using archive tissues for studies. Requests are evaluated and prioritized based on several factors, including overlap with other studies, alignment with the NWRC’s mission, and availability. The Center cooperates with Federal, State, and Tribal government agencies, universities, and nongovernmental organizations. For more information, please contact Dr. Tim Smyser at Timothy.J.Smyser@aphis.usda.gov or 970-266-6365.

NWRC is the research arm of the USDA Wildlife Services program. Wildlife Services is a Strategic Partner of The Wildlife Society.

Header Image: Feral swine hair sample. Part of the Wildlife Services feral swine genetic archive. ©USDA Wildlife Services