Share this article

Plenary speakers stress diversity, inclusion in changing field

Nalini Nadkarni said she’s a bit envious of wildlifers. As a plant biologist trying to explain to the public the importance of forest canopies, she said, “trees can be a hard sell.”

But the University of Utah biologist has made her pitch through a diversity of approaches, from inviting rap artists to the forest to hoisting state legislators into canopy stands, from presenting nature videos to prisoners in solitary confinement to slipping her PowerPoint show into the view of the person seated next to her on the plane.

Even her clothes send a message. As she stood at the podium for Tuesday’s plenary at TWS’ 24th Annual Conference in Albuquerque, N.M., she wore a jacket with a print of botanically accurate leaves of the tropical Piper auretum. Her outfit, she said, becomes a way to start conversation about rainforest protection at a conference or in line at Starbuck’s.

“I invite you to think of all the people you might weave into a tapestry of conservation,” Nadkarni told the crowd.

Speakers at the plenary, “Paradigm Shifts, Diversity and Inclusion and Feet in Several Worlds,” encouraged wildlifers to think beyond their traditional constituencies and approaches to conservation, from sparking interest in conservation in new communities to embracing wildlife enthusiasts who don’t come from a hunting and fishing background.

“This is not your grandfather’s wildlife conservation,” said Jennifer Malpass, a biologist at the U.S. Geologic Survey’s Patuxent bird banding lab.

Throughout its history, Malpass said, wildlife professionals have faced a series of “adapt or die” choices. At the turn of the century, conservationists concerned about game species rose up to stem a wave of extinctions. In the 1970s, the profession reached beyond game management as the public worried about environmental threats brought on by pollution.

Now, the profession faces its third challenge, she said, as a new generation arrives with wildlife interests beyond hunting and fishing.

“Enter the millennial wildlife professional,” Malpass said. “Although some millennials are modern-day Aldo Leopolds, others of us don’t look a lot like those 1930s wildlife professionals. My path to the profession started with me flipping rocks in my suburban Chicago backyard, looking for interesting critters underneath.”

Those millennial biologists, often from non-traditional educational programs and steeped in notions of diversity and collaboration, are essential to the profession staying relevant, she said.

“Look to us to help bridge the divides among the four, and almost five, generations of wildlife professionals currently in the workforce,” she said. “Ask us why we got into this field and you may find surprising similarities to your own experience, even if we’re from the city or are non-hunters. Only by working together will we be able to honor our roots while maintaining our relevance.”

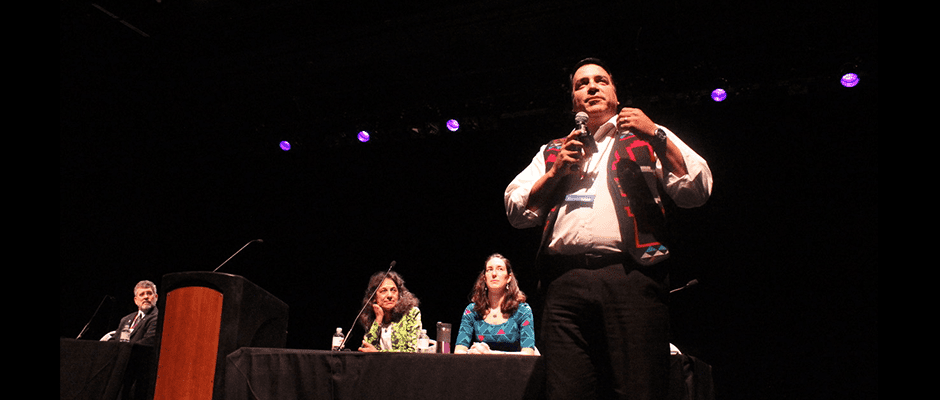

Scott Aikin, the National Native American Programs Coordinator for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and a member of the Prairie band of the Potawatomi Nation, underscored the need to reach out to diverse audiences.

“I want to invite your perspective in and be transformed by hearing that, and ask you to be transformed by hearing my position,” he said.

“The commonality of what’s presented here, and I present to you,” Aiken said, “I cannot say strongly enough, resonates beyond a chance. It’s meant to be.”

The following awards were handed out:

Donald H. Rusch Memorial Game Bird Research Scholarship: Andrew Olsen

Group Achievement Award: Thunder Basin Grasslands Prairie Ecosystem Association, Dave Pellatz

Header Image: Scott Aikin, the National Native American Programs Coordinator with USFWS, is provided his insight into the wildlife profession as a Potawatomi tribe member.