Share this article

New study suggests monarchs aren’t so imperiled

Concerns about monarch butterfly populations have made them contenders for Endangered Species Act protections, but a new study contradicts those fears, finding that monarchs are not in as much trouble as conservationists think.

On their summer ranges in North America, researchers found, monarch populations aren’t just stable. They’re growing slightly. Even though their numbers are low at wintering ranges in California and Mexico, the study published in Global Change Biology found, they rebound at their summer ranges.

“We’re left with this tragic irony where we are on the verge of listing this species as endangered that is doing absolutely fine and is one of the most—if not the most—abundant butterfly in North America right now,” said Andy Davis, a research scientist at the Odom School of Ecology at the University of Georgia and the corresponding author on the study.

The findings have been met with skepticism from some butterfly researchers, who question the analysis.

Past research has found that in some areas, monarch butterflies (Danaus plexippus) are declining due to a lack of milkweed, which caterpillars feed on and adults lay their eggs on, and that monarch numbers on their wintering grounds are falling. That has concerned conservationists, who have rallied behind efforts to boost milkweed production and protect the butterflies.

In 2020, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service determined that adding the butterfly to the list of threatened and endangered species was “warranted but precluded” by higher priorities, but it remains a candidate. Based on declining numbers at overwintering colonies over the past 20 years, biologists found that the eastern population fell from about 384 million butterflies in 1996 to 60 million in 2019. They determined the western population, which migrates to California, declined from about 1.2 million in 1997 to fewer than 30,000 in 2019. The Service has relied on winter colony sizes as proxies for population size, but this new study suggests that should be reconsidered.

Can summer gains make up for declining monarch butterfly numbers on their wintering grounds?

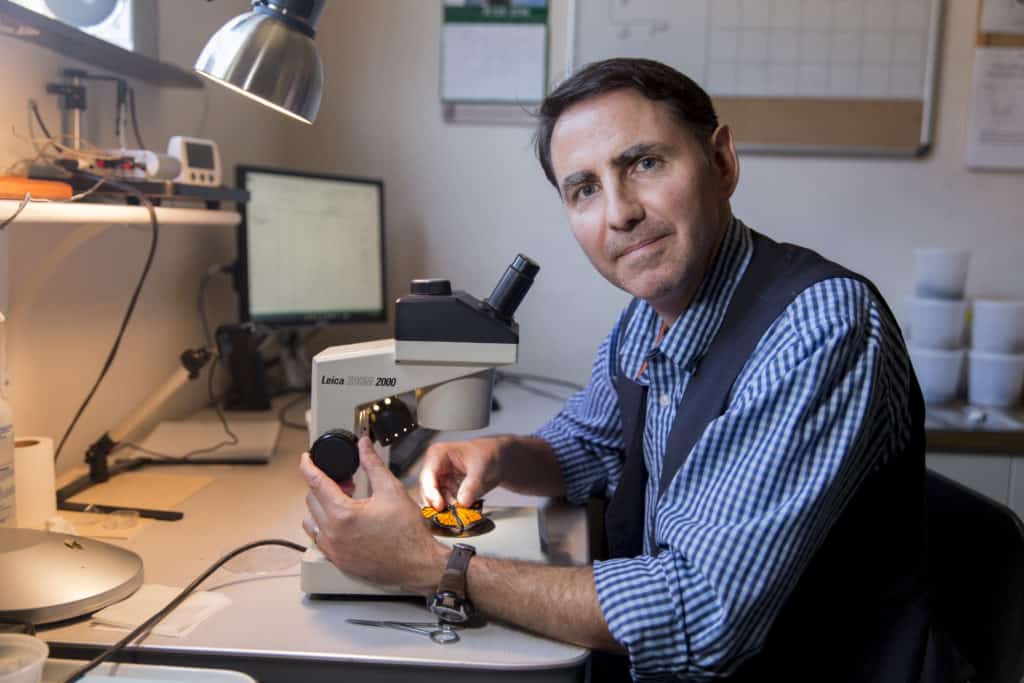

Credit: University of Georgia

In the latest research, a long-running effort to find out how the butterflies are faring across North America, Davis and his colleagues tapped into a citizen scientist program run by the North American Butterfly Association, or NABA.

As part of the program, volunteers go to specific sites around the U.S. and Canada each summer to log every butterfly they see—not just monarchs. Between 1993 and 2018, the team tallied 130,000 monarch observations.

Reviewing these numbers, the researchers found that monarchs were doing just fine in North America. Their annual relative abundance actually increased 1.36% each year.

That suggests a disconnect between populations gains in the summer and losses in the winter. Most researchers have associated declines in Mexican and Californian wintering colonies with an overall population decline. But Davis argues that doesn’t appear to be the case. While some parts of the U.S. and Canada are seeing monarch declines, he said, those are balanced out by other areas where monarchs are on the rise. “If you collectively pool those together, there’s no downward trend,” he said. “And that’s surprising to a lot of people.”

Some butterfly biologists are skeptical, though. “NABA is a great community science project, but the monarch has such a complex migratory cycle that summer counts are not the whole picture,” said Emma Pelton, senior endangered species conservation biologist with the Xerces Society, a nonprofit invertebrate conservation organization.

Volunteer surveys often are conducted in natural areas, so they don’t capture losses that may be occurring in agricultural or urban setting, said Pelton, who reviewed the study in preprint. “We need better data driving us,” she said.

She supports the USFWS data and worries a debate about whether or not winter butterfly numbers reflect summer numbers will distract from conservation efforts. “You typically think about the viability of an animal by looking at when the population is the smallest and most vulnerable,” she said.

Without conservation efforts to address the decline in winter populations, Pelton said, summer populations won’t be able to rebound. “When I think about how this affects the public and what they need to do, the debate is a little beside the point,” she said.

Monarch numbers do fall as they migrate to wintering grounds, Davis said, likely due to roads, extreme weather or other factors. “Probably only 30% actually reach the wintering colony,” he said. “It’s a transit issue.”

But the new findings suggest their population recovers in the summer, when a single female can lay up to 500 eggs. “It’s just basic math, really,” Davis said.

Header Image: Monarch butterflies are being considered for federal listing, but researchers think they’re doing just fine in North America. Credit: Katriona McCarthy