Share this article

Motorboats disrupt cooperation between cleaner fish and their clients

The world of cleaners and clients sounds more like one of domestic labor than of coral reefs, but the unique symbiotic relationship between cleaner fish and their clients helps keep these underwater systems healthy. Cleaner fish eat the parasites off client fish, but left to their own devices, they tend to cheat. So the clients keep an eye on the cleaners to make sure they’re doing their job.

The system works for both fish — until a noisy motorboat passes by. The sound seems to distract the fish, biologists found, disrupting the delicate balance between them. Researchers studying coral reefs in French Polynesia believe boat noise may cause cleaner fish to cheat more on their clients and spend less time eating parasites, a finding that raises concerns about impacts on the health of reef systems.

“We did see an increase in cheating,” said Sophie Nedelec, lead author on the study published in the journal Scientific Reports. “It seems that either or both parties are getting distracted.”

Previous research has shown that motorboat noise distracts or stresses many underwater species. To investigate how it affects cleaner fish and their clients, Nedelec, a postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Exeter, and her colleagues conducted a series of dives. They studied 24 cleaner fish stations for an hour each, examining what happened before, during and after a boat with a two-stroke engine motored overhead.

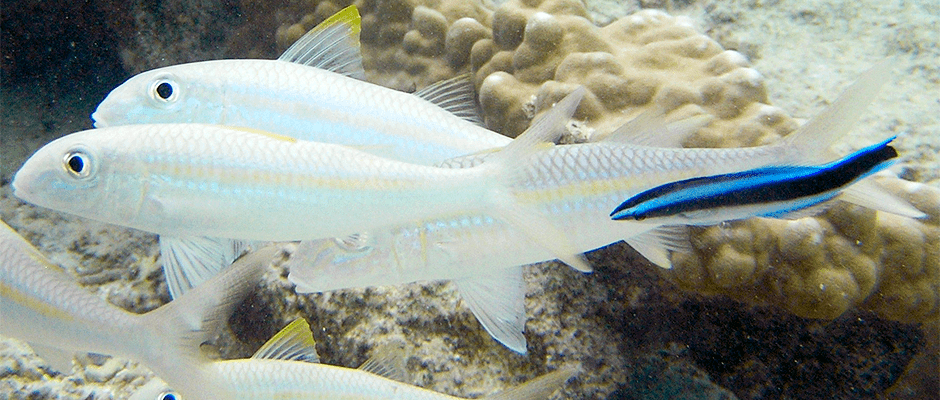

Working out of the CRIOBE research station on the South Pacific island of Mo’orea, Nedelec’s team studied bluestreak cleaner wrasses (Labroides dimidiatus) and their fish clients. Unlike cleaning gobies (Elacatinus), fishbowl favorites that faithfully devour parasites, wrasses prefer a menu of mucus, so they tend to cheat their clients by nibbling the protective layer on their clients’ bodies instead of parasites.

Each day, Nedelec said, a cleaner can see over 1,000 clients, which watch it perform its job as they wait to receive its services. The clients keep track of individual cleaners they catch cheating, break away or chase them as punishment and avoid visiting them in the future. The cleaners, too, are aware of how many times they’ve taken advantage of individual clients, and they try not to game the system so often that they cheat themselves out of food.

This interplay changes when motorboats arrive, Nedelec said. Cleaners spend more time inspecting their clients and are less inclined to eat parasites. Clients, in turn, retaliate less against cheaters. Nedelec believes the change may be due to cognitive impairment caused by motorboat noise.

“If the clients knew what was going on, they’d leave sooner, but we saw the opposite and didn’t see any change in their rate of chasing of cleaners,” Nedelec said. “Maybe clients are not realizing they’re being taken advantage of and cleaners are getting away with more mucus and fewer parasites.”

If this change in the cooperative behavior between cleaner and client decreases parasite removal, she said, “the health of coral reef fishes would be in jeopardy because the presence of cleaners on reefs is vital for fish that live there.”

Nedelec and other researchers are hopeful that alternative motor types, such as four-stroke engines, may be less harmful to marine life. Various management policies could help to reduce boat noise pollution and its possibly harmful effect on cleaner-client interactions and the broader ecosystem, she said, including limits on boat speed, distance or engine type around coral reefs.

Header Image: A cleaner fish (Labroides dimidiatus) inspects a yellow-striped goatfish (Parupeneus chrysopleuron) for parasites