Share this article

JWM: Trail cameras can help scientists estimate elephant density

At a shoulder height of nearly eight feet, an elephant may seem easy to spot. But these giant mammals are surprisingly cryptic in the forest ecosystems they occupy. As a result, researchers often estimate the density of the large mammals using what they leave behind—their droppings.

The trouble is, in humid forests where rain is common, like the Aberdare Conservation Area in Kenya, it’s difficult to tell how fresh a pile of dung might be. This uncertainty can affect the way that wildlife researchers determine elephant density. It’s also time consuming and expensive to count elephant dung through the thick bush.

“You can spend days and days of just not seeing an elephant at all,” said Jacqueline Morrison, an associate lecturer at the Manchester Metropolitan University.

Morrison and her colleagues wondered if trail cameras could provide an additional tool for accurately estimating savanna elephant (Loxodanta africana) density along with the dung count survey method. As part of a study published recently in the Journal of Wildlife Management, they used photos that the Manchester Metropolitan University captured as part of a larger study on wildlife in the Aberdare Conservation Area.

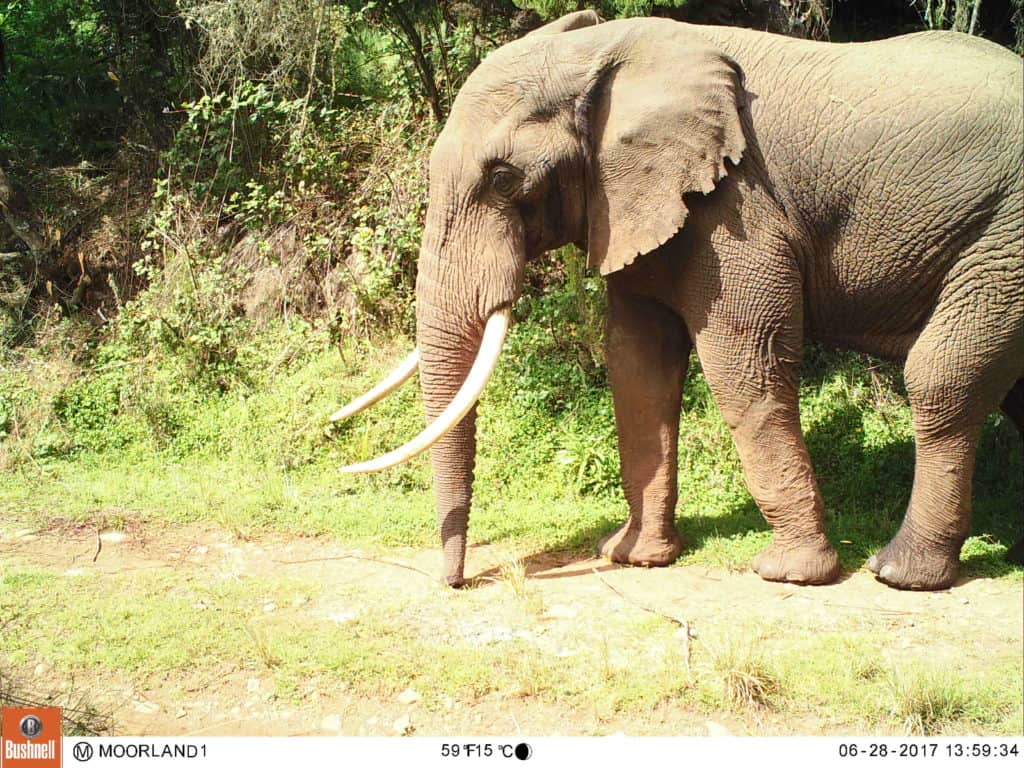

Trail camera surveys may be cheaper and involve less staff hours than dung counts. Courtesy of Jacqueline Morrison

Morrison and her team proportionately sampled photographs that represented the different types of ecosystems that savanna elephants used in the areas: bamboo, moorlands, forest and shrub. They also placed a few of their own cameras that weren’t part of the wider survey in underrepresented ecosystem types to balance their study out. In all, they deployed 65 cameras from June to August every year from 2015 to 2017.

The researchers combed through tens of thousands of captured photos of savanna elephants. They found the animals in 16 locations, mostly in shrubs, followed by forests, bamboo and moorlands.

Scientific models helped them estimate the density of elephants in the area from the trail camera information. Densities from the models, they found, closely matched densities recorded during another survey conducted using the dung count method.

“Our method mirrored what they found,” Morrison said.

Not only did the camera method appear to be produce comparable results to the dung counting method, but it’s a lot less labor-intensive, only requiring the initial fieldwork of setting up the cameras, then picking them up at the end of the study period.

Morrison stressed that rather than replacing dung surveys, this new method should be used as an additional way to validate the estimates of elephant density in a given area. One of the reasons for this is that researchers still haven’t achieved complete validation of either method in mountain forest environments, since the real total of savanna elephants in the area is unknown.

This article features research that was published in a TWS peer-reviewed journal. Individual online access to all TWS journal articles is a benefit of membership. Join TWS now to read the latest in wildlife research.

Header Image: Trail cameras provide an additional survey technique to traditional dung counts. Courtesy of Jacqueline Morrison