Share this article

JWM: Landfills bolster wild pig numbers

Landfills may bolster wild pig numbers by providing a supplemental food source, increasing their size and boosting reproduction.

The giant trash heaps might also serve as vectors for the transmission of diseases and cause an increase in vehicle collisions nearby.

“Nobody is highlighting this problem of wild pigs and landfills,” said TWS member John Mayer research and development manager for the Savannah River National Laboratory of Savannah River Nuclear Solutions LLC.

Mayer has been studying wild pigs (Sus scrofa) since 1973. While talking with his colleague John Kilgo from the U.S. Forest Service Southern Research Station, also a TWS member, who was running telemetry tracking research on wild pigs in South Carolina, the two noticed the swine’s massive size after a landfill was put into the U.S. Department of Energy’s Savannah River Site in 1998.

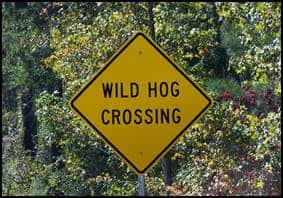

Signs like this surrounding the landfill at the Department of Energy’s Savannah River Site were the among the first put up in South Carolina.

Credit: John Mayer

“These things were huge, much larger than some of the pigs we usually see on the site,” Mayer said. “There was something going on at that landfill that was out of the ordinary.”

In a study published recently in the Journal of Wildlife Management, the two researchers and others looked more deeply at the effects of the landfill on wild pigs.

They found that pigs were indeed getting bigger from 2000 to 2019 compared to their size 20 years before the landfill was created. They also noticed an increase in litter size around the landfill compared to wild pigs in the general area.

The density of wild pigs harvested in a given area also increased by nearly three times, and vehicle collisions involving hogs began happening in areas that had previously experienced none.

“The pigs foraging in the landfill get bigger,” Mayer said. “That creates two problems: Bigger sows create bigger litters, and bigger pigs in general cause bigger risks with respect to vehicle collision.”

In the 310-square-mile area that includes the landfill, Mayer estimates there are more than 5,000 wild pigs.

The damage wild pigs cause ecologically is well-documented. They are ecosystem engineers, changing wetland ecosystems and outcompeting native species for food. They can also uproot crops and cause other agricultural damage.

But Mayer worries that landfills could be the source of even more pig damage, become a flashpoint for the spread of a disease that has devastated the pork industry in countries across Asia and Europe — the African swine fever. While this disease has yet to be detected in North America, some researchers believe it’s just a matter of time before the disease makes the jump.

A feral hog moves through the landfill site. Credit: Kyle Cox

The virus can persist in uncooked pork products that people may bring with them while traveling. Even if airport customs officials flag the food, it often gets disposed in landfills. If living pigs come into contact with contaminated meat, they could contract the disease.

In fact, landfills are believed to be one of the primary ways the disease has spread through Eurasia. When feral pigs come into contact with domestic pigs, they can pass on the disease, which kills every hog that catches it.

“It’s the kiss of death with respect to domestic pigs,” Mayer said, adding that in 2019 China had to euthanize a massive number of domestic pigs to stem the spread of the disease.

Pig removal at the landfill he studies in South Carolina isn’t really an answer, Mayer said. It can be difficult for managers to remove the pigs because they usually forage on the landfill at night when no one is around to do anything. And even when individuals are removed, the source population from the surrounding area is large enough that they are quickly replaced.

“We really need to fence our landfills,” he said.

While landfill operators are reluctant to spend the money to build such infrastructure to keep swine out of the trash, the stakes of not doing it for the $97 million-a-year U.S. pork industry are much higher.

“The consequences of not doing that are a lot more severe than they realize,” Mayer said.

This article features research that was published in a TWS peer-reviewed journal. Individual online access to all TWS journal articles is a benefit of membership. Join TWS now to read the latest in wildlife research.

Header Image: Trash in landfills are bolstering swine numbers. Credit: Chris Conway, Hilleary Osheroff