Share this article

If you can’t save everything, how do you choose?

If you can’t save all the endangered species in the world, which ones do you choose?

It’s not an easy question for conservationists, but they do have a way to answer it: choose species with the most diverse traits. To do that, they’ve relied on picking species with diverse genetic lineages. But that’s taking a chance — a “phylogenetic gambit” that diversity in evolutionary history, or phylogenic diversity, translates to diversity in traits, or functional diversity.

Does that gambit pay off?

“It’s a risky proxy,” said Florent Mazel, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of British Columbia and lead author on a study in Nature Communications looking at how well phylogenic diversity stands in for functional diversity.

The idea can get abstract, but its core is simple. If you have, say, a mouse, a rat and an elephant, Mazel said, and you can only save two of them, which two do you save? Well, the elephant is a given, because its traits are so distinct from the mouse and the rat.

“When we talk about maximizing diversity, it’s about taking species far apart on the tree of life,” he said.

He and a group of colleagues from Canada, the United States, Argentina, England and France, funded by Germany’s Synthesis Center for Biodiversity Sciences, set out to test how well phylogenic diversity acted as a surrogate for functional diversity in an effort to help conservationists choose which species to concentrate their efforts on.

Having limited resources to deal with widespread extinctions “poses an immense moral challenge,” the researchers wrote. “Agonizing choices as to which species most warrant attention become necessary.”

It’s been largely a theoretical question, but it is having real-world impacts. “Some initiatives are starting to show up,” Mazel said, including a British effort, EDGE of Existence, which seeks to prioritize species that are “evolutionarily distinct and globally endangered.”

Mazel’s team looked globally at more than 15,000 vertebrate species — mammals, birds and tropical fish — to see how well phylogenic diversity matched up with functional diversity. For the most part, they found, the gambit holds. Preserving phylogenetic diversity preserves 18 percent more functional diversity than random selection.

But it doesn’t always work, Mazel said, and that’s what makes it risky. About one third of the time, it actually preserved less diversity than random samples.

“It’s not reliable,” he said. “Even if on average it works, it won’t work all the time.”

Mazel said he’d like to see the study repeated with more species, including plants, to see if the results are similar. But in the end, he said, the gambit seems to pay off, even if it doesn’t work all the time.

“Even if we say it’s risky,” he said, “it still holds.”

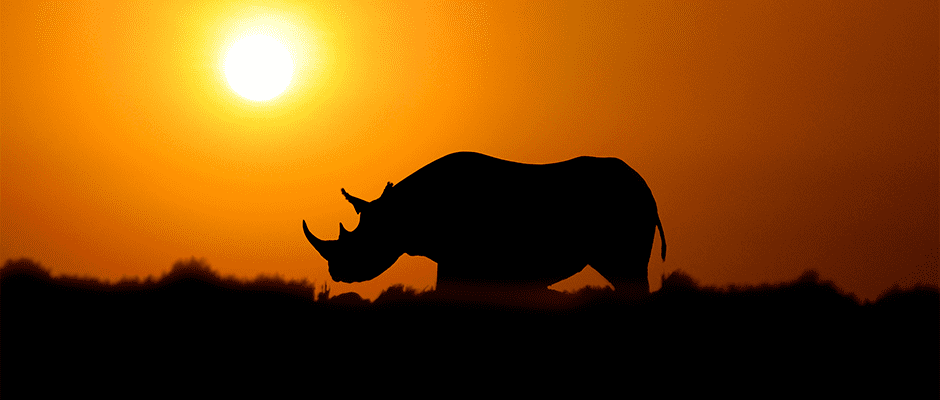

Header Image: When protecting endangered species, some conservationists suggest targeting species with unique traits, like the black rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis). Image Credit: Ray Morris, licensed by cc 2.0