Share this article

Human conflict kills wildlife as well

The toll of war isn’t limited to human casualties. Biologists recently found that since the mid-20th century, as conflict has become more common across Africa, mammal populations in turbulent areas have rapidly deteriorated, requiring greater conservation efforts in wildlife parks and neighboring communities.

“War had a consistently negative impact on wildlife in Africa,” said Joshua Daskin, first author on the study published in Nature. “The more the conflict, the quicker the decrease in population density.”

In 2013, Daskin, then a doctoral candidate at Princeton University, and his advisor Robert Pringle, an assistant professor of ecology and evolutionary biology, started collecting information on populations of big herbivores throughout African warzones. They pulled 253 population trajectory estimates from scientific papers and government and nonprofit reports published between 1946 and 2010. Focusing on 126 protected areas in 19 countries, they looked at species such as the elephant (Loxodonta spp.), wildebeest (Connochaetes spp.), zebra (Equus spp.), Cape buffalo (Syncerus caffer) and waterbuck (Kobus ellipsiprymnus). The researchers examined changing wildlife counts in the context of conflicts using databases from the Peace Research Institute at Oslo and Uppsala Conflict Data Program that noted where and when such events occurred. The results confirmed their suspicions.

“As conflict frequency increased, the rate at which populations declined increased,” Daskin said. “As little as one conflict event in two decades makes an average population decline.”

Warfare can have a positive effect on wildlife, in places like the Korean Demilitarized Zone, which acts as a protected area because it’s too hazardous for people to occupy, Daskin said. But in Africa, the researchers found, political violence has seriously affected wildlife. During Mozambique’s 15-year civil war, when Gorongosa National Park served as the base for both rebel and government forces, the park lost over 90 percent of its large mammals to poaching, Daskin said, as conservation took a backseat to combat.

Wartime also can bring other problems that stand in the way of conservation efforts.

“Poverty tends to increase during conflict, so food insecurity becomes a problem,” he said. “Large mammals are sources of meat. Poaching increases in conflict zones due to food insecurity and a reduction in law enforcement as well as huge movements of militaries or refugees into protected areas where wildlife are sitting targets.”

But even in the aftermath of violent upheaval, Daskin said, wildlife populations can persist and bounce back.

“Populations hold on at low levels,” he said. “There’s great potential for the restoration of postwar landscapes. Conservation managers should not write these areas off as lost.”

In Gorongosa, Daskin said, mammals have rebounded over the last fifteen years to 80 percent of prewar numbers, thanks to strengthened antipoaching patrols and local economic circumstances that lessen the demand for bushmeat.

“It can take a surprisingly short period of time for wildlife to recover when the conditions necessary are put in place,” said Daskin. He is now analyzing the link between war and deforestation.

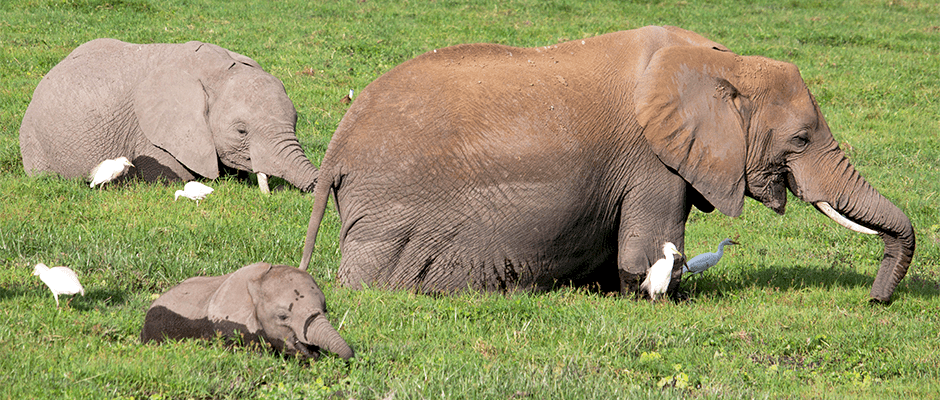

Header Image: Elephants wade through Kenya’s Amboseli swamps. ©Joshua Daskin