Share this article

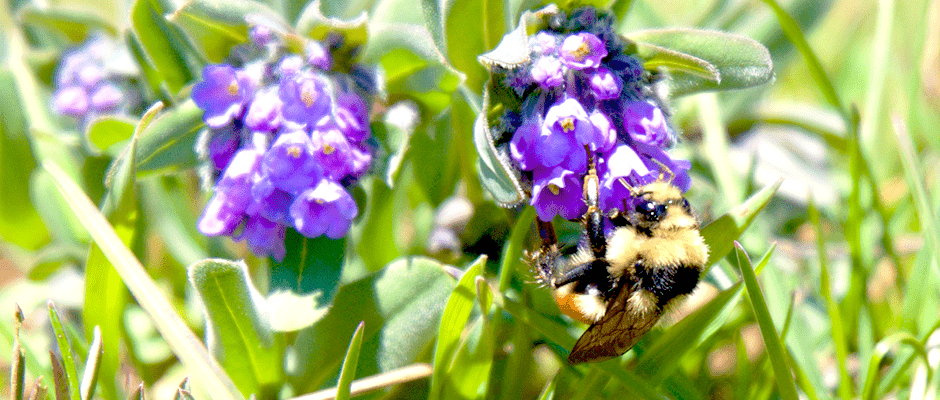

Climate change may be depriving bumblebees of food

Bumblebees gather pollen twice as fast as honeybees, but new research from Colorado suggests that climate change may be straining the wildflowers available to bumblebees and threatening their populations’ survival.

The bees are facing too many days with too few flowers, putting them at risk of “using more resources to look for food than they get back,” said Jane Ogilvie, lead author on the paper in Ecology Letters. “The number of poor-resource days are increasing with climate change, so that leads us to be concerned about bumblebees over the long term.”

Ogilvie, a postdoctoral research fellow with the Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory, and her colleagues modeled data on bumblebee population size, flower abundance and climate to investigate how climate change impacts three bumblebee species (Bombus spp.). Past studies had shown that it was making the insects active earlier in spring and shifting their ranges, but her team wanted to dig deeper.

The researchers found that the warming climate was extending the wildflower season. Flowers started to bloom earlier. But that didn’t result in more flowers, they found. Instead, it meant more days with fewer flowers for the bumblebees to forage, Ogilvie said, like taking enough peanut butter for half a piece of toast and spreading it over a whole slice.

“The more good flower days they have, the more bumblebees there are,” Ogilvie said. “Snow is melting earlier over the last four decades, so we’re getting longer flowering seasons, but there’s more poor-resource days occurring in a season. We’re getting the same number of flowers spread out over more days.”

Ogilvie and her fellow researchers have been counting bumblebees during flowering season at a small site in Crested Butte, Colorado, since 2009 and the flowers blooming there since 1974. Every year, the biologists noted the sum of flowers up until the day they found the most bumblebees. They also looked at the number of days in a season that had enough flowers within the bees’ foraging ranges to meet their energy needs — the scientists gauged that the bees needed at least three flowers for every four-square-meter plot.

Ogilvie believes the overall amount of resources bumblebees have has remained constant despite the longer flowering season because early-season frost, which occurs regardless of climate change, damages plants and limits blooms. Early snowmelt in high-altitude environments such as the study area could also hinder flower production because plants rapidly consume the moisture and face drought in the middle of the extended season, she said.

“When there are periods of days where there’s not good flower availability, bumblebee colonies can suffer,” Ogilvie said. “They only store enough nectar and pollen to get through a couple days without being able to forage. Food shortages becoming more common could negatively affect bumblebee population sizes.”

She’s now studying how bumblebees might visit a broader variety of flowers to cope with the reduction in their usual food supply due to climate change.

Wild bumblebees are also in decline because of pesticide use, parasite transmission from commercial bees and loss of habitat to farms and cities, Ogilvie said.

“If we’re restoring habitat or trying to sustain bumblebees in agricultural or urban places,” she said, “we should consider planting wild flowers that span the entire season.”

Header Image: Bombus bifarius visits spring bluebells in a subalpine meadow in Colorado. ©Jane Ogilvie