Share this article

A look at the possible role of bacteria in plumage degradation

All birds normally fly around with bacteria on their wings, but researchers wanted to know how those microorganisms affect their plumage.

In the study published in the Auk: Ornithological Advances, researchers collected data from more than 3,500 live birds that included 154 different species such as cardinals, house sparrows, song sparrows, woodpeckers and others that were captured between 1996 and 2005 in Ohio, Louisiana, Maryland, Washington, Arizona and the Bay of Fundy. Lead author and PhD student at Tulane University Cody Kent and his colleagues tested the birds’ feathers to determine to what extent three species of bacteria from the family Bacillus affect their feathers as well as which bird species were most likely to have bacteria on them.

A researcher hold a Carolina chickadee, one of the species that’s feathers were sampled in this research. ©Cody Kent

Kent says that previous research showed bacteria can break down bird feathers in the lab, but it had not been shown on wild birds. Other studies had looked at possible evolutionary implications of the birds’ color and behavior as a result of bacteria.

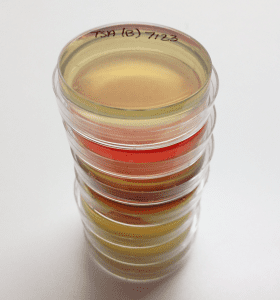

He and his colleagues wiped the birds’ feathers on petri dishes to culture and grow the microorganisms living on their feathers. They then separated the species into foraging categories: ground-foraging, aerial-foraging, fly-catching, nectivorous, marine-foraging and tree-probing birds. The results showed that ground-foraging, aerial-foraging and fly-catching birds had more of the bacteria on their wings compared with nectivorous, tree-probing and marine-foraging birds.

The team also found for the first time that the bacteria can break down wild birds’ feathers and that those individuals with more of the bacteria had higher levels of wear. This feather degradation can impair the birds’ flight ability and might also make mating behaviors more difficult, according to Kent. “Some birds have mating signals where they use their plumage,” Kent said. “Bacteria can break those down easily, so there’s a not-so-nice display.”

But feather degradation might also have a positive effect on bluebirds, causing its feathers to become a brighter blue and leading to more mating behavior. Kent says brighter feather color has been associated with more offspring, but on the flipside a brighter color could cause more predator interactions.

Petri dishes were used to sample bacteria on the birds’ feathers. ©Cody Kent

In theory, Kent says this research could be applied to endangered species to determine how and if more bacteria on their wings is affecting them. But the crux of his work is tied to answering more evolutionary questions. “It’s a complex relationship between birds and bacteria,” he said, adding that birds have been living with the bacteria for thousands of years. “I think it’s an interesting thing in this line of research going forward. I think that microbial ecology is on the forefront ecological questions at the moment.”

Kent worked on this research with his coauthor Edward H. Burtt who passed away before the research was published. “Kent and Burtt’s new study is a tour de force,” said Dale Clayton, a University of Utah ornithologist who was not involved with the study, in a press release. “It underscores the potential importance of feather-degrading bacteria as selective agents that may influence the evolution of birds in important ways. Tragically, Jed Burtt passed away prior to final publication of the paper, which is a fitting tribute to his lifelong love of birds and his pioneering work on the creatures that live on them.”

Header Image: A bluebird perches on a branch. ©Andy Jones