Share this article

Climate change, not land use, is driving deer north

The northward spread of white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) may be unstoppable, according to new research. Deer have been creeping north for decades, invading Canada’s boreal forests and creating problems for caribou (Rangifer tarandus). People have long attributed deer expansion to land use changes such as farming and logging, which land management could theoretically control. But a new study suggests that the primary reason is irreversible warming of Earth’s climate.

“We just need to accept that deer are now a boreal species, even though they historically weren’t considered to be,” said TWS member Kimberly Dawe, a wildlife ecologist at Quest University Canada and lead author of the recent study in Ecology and Evolution. “We’re looking at local management rather than managing the expansion, because it’s essentially bigger than us.”

Since the early 20th century, white-tailed deer have steadily spread past their former range limit at the southern edge of the boreal forest. Their expansion has been particularly dramatic in Alberta, with deer abundance in the northeastern part of the province increasing more than 17-fold since the 1990s. The deer have supported larger populations of wolves, which in turn have increased predation on federally threatened caribou.

Until now, many people have assumed that deer were simply taking advantage of land-use changes, moving into farmed and recently logged areas to eat new plant growth. But while deer clearly favor disturbed areas, the underlying cause of their range expansion was obscure, says Dawe. Some researchers suspected that the real limiting factor was not food, but cold.

“At the northern extent of the range, we think that climate, and winter weather in particular, is what stops them from living any further north,” said Dawe. “It may actually just be that the boreal forest is now a happier place for them, because they’re not getting killed off in the winters.”

To put this hypothesis to the test, Dawe and her colleagues created a mathematical model based on where deer were found in Alberta during the 2000s. Then, they used data from previous decades to show that the model could accurately predict deer distribution under different conditions. While land use had some impact on deer distribution, the effect of climate was much stronger. When the researchers projected climate change trends into the future, they found that white-tailed deer would likely spread more than 60 miles further north in northeastern Alberta by the 2050s, increasing their total range by more than 50,000 square miles.

While land managers can’t control the climate, they may still have some options. The model only looked at whether deer were present in an area, not how many lived there, so it may be possible to reduce deer abundance through hunting and land management. Dawe is now developing a model that includes abundance data, and she hopes the new model will help managers combat deer and protect caribou. But no matter what they do, managers probably won’t be able to get rid of the deer completely.

“We can’t just restore the landscape and get deer out of the boreal,” said Dawe. “They are here to stay.”

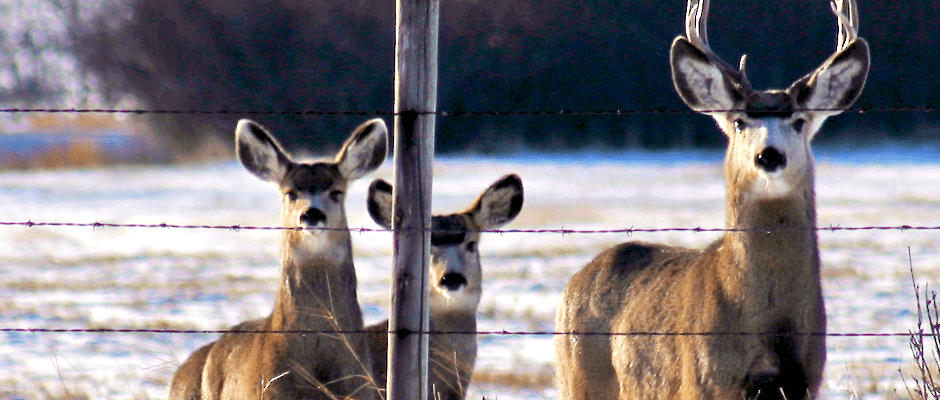

Header Image: White-tailed deer stand in the snow in Alberta, Canada. New research suggests that mild winters in Alberta are allowing the deer to spread north. ©Chris Pawluk