Share this article

Watersnakes help gauge mercury presence in streams

The tips of watersnakes’ tails retain levels of mercury that could indicate how contaminated rivers and streams are with toxins.

“One of the advantage of brown watersnakes is they have a really high site fidelity,” said David Haskins, a PhD candidate at the University of Georgia and the lead author of a study published recently in Science of the Total Environment. “It gives you a nice little snapshot of what’s going on in that area.”

Brown watersnakes (Nerodia taxispilota) are found throughout the eastern United States. While scientists usually use fish as a model species to test for mercury levels in a given area, fish usually swim around a wider area, making it harder to pinpoint the mercury quantity in specific areas. Watersnakes, on the other hand, eat contaminated fish, consuming the mercury inside of them in the process. The reptiles also often stay put in smaller areas than many fish, which makes them better heralds of potential contamination at a specific site. Since mercury bio-accumulates in the snakes’ bodies over time, Haskins thought these reptiles may be better indicators of the mercury contamination in a given waterway.

To test this theory, he and his team caught watersnakes on the Savannah River system in the summers of 2017 and 2018. “It was a blast. You get to get out on the water and see all kinds of stuff — eagles, sturgeon, bobcat,” he said.

They set out by boat, capturing more than 120 snakes and snagging the reptiles as they basked on rocks in the river. Other studies sometimes used alligators (Alligator mississippiensis), but those can be “more temperamental and dangerous,” Haskins said. “Brown watersnakes are easier to catch if you don’t mind getting bit.”

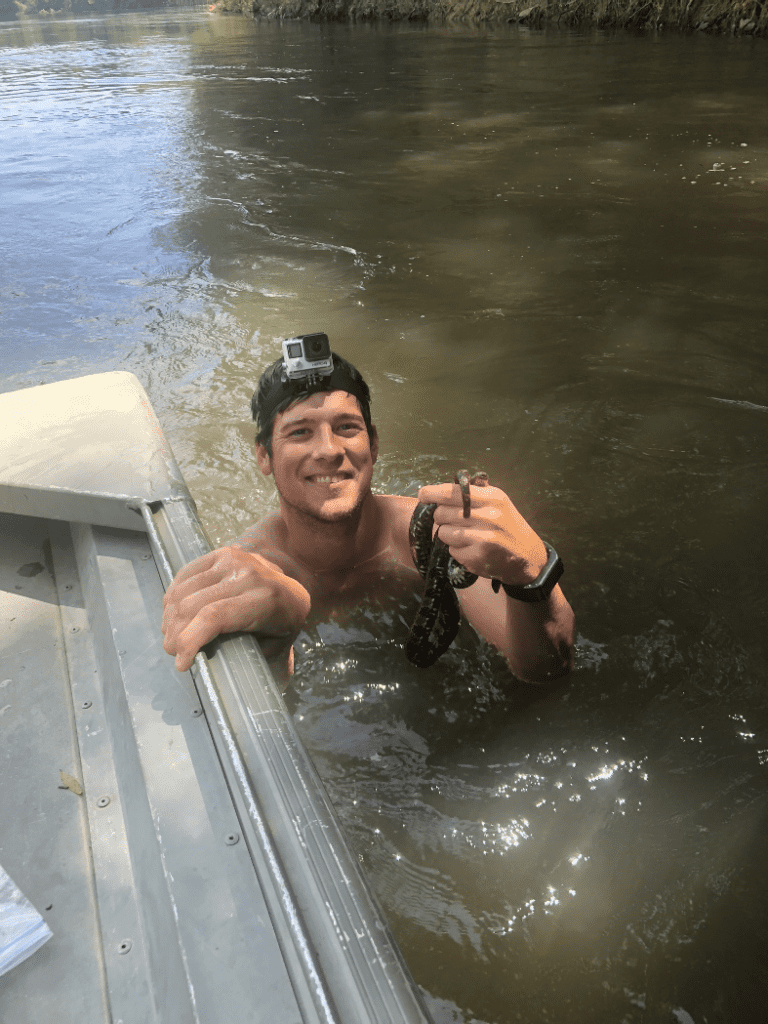

Researchers jumped off boats, into the Savannah River to catch watersnakes. Credit: David Haskins

They captured snakes in four main regions of the river with varying levels of mercury known from studies on other species. Once they captured the snakes, they took blood samples and cut the 1-centimeter tips off the end of their tails. The tail clipping is much easier and quicker than blood extraction, and the researchers wanted to validate that such a method worked just as well.

“They were extremely correlated,” Haskins said. “It was basically a validation of what had been done previously.”

They also found that the snakes’ mercury levels correlated well with other species used as indicators. In addition, snakes seemed to accumulate mercury from prey they eat — or “bio-magnify” — compared to the fish tested previously in the region.

“As our brown snakes got bigger, they had higher amounts of mercury,” Haskins said.

Overall, the mercury levels in the Savannah River system isn’t that much of a concern these days, Haskins said. Augusta, Ga. used to have a number of bleach plants that heavily polluted the area, but those levels have since died down. Haskins said most of the contamination in the area is now atmospheric, meaning the mercury is either from natural sources, or comes from fumes that travel widely from the power plants that produce them.

A watersnake consumes a large meal. Credit: David Haskins

“The mercury content in these snakes relative to other areas is actually pretty low,” Haskins said.

He believes this study shows that snakes could be used in a number of other waterways as bio-indicators of contamination — and not just mercury. Researchers in Florida, for example, could use Burmese pythons (Python bivittatus) to track contamination in the Everglades.

Header Image: David Haskins and another researcher extract blood samples from a brown watersnake. Credit: David Haskins