Share this article

Sniffing out shrubs’ significance for endangered lizards

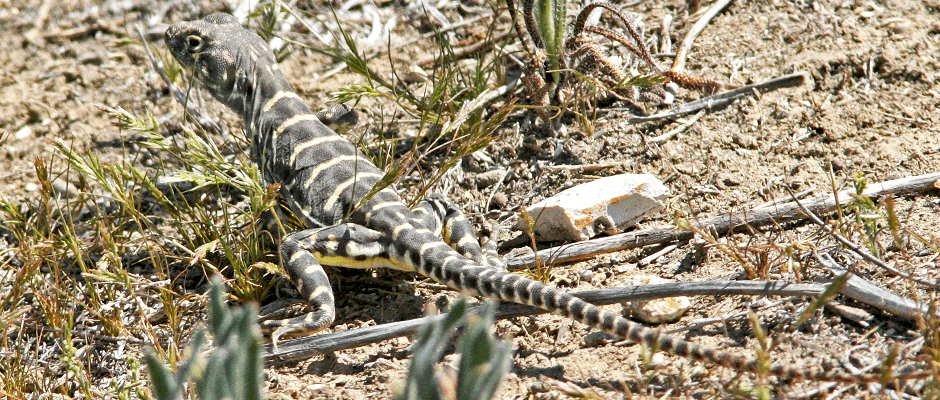

Endemic to California’s San Joaquin Valley, the blunt-nosed leopard lizard (Gambelia sila) has been fighting extinction for the last half-century. With a little assistance from a team of scat-sniffing canines, researchers have now found that managing shrubs in the lizard’s arid habitat may help conserve the species.

The ecologists came across the lizards’ droppings more frequently in places with less invasive grass cover or under dense shrubs. They concluded that maintaining the shrubs and controlling the nonnative plants could better support the endangered lizard, which may rely on the shrubs for shade in the arid environment.

“If that’s true and climate change models are predicting California to become warmer, we might expect lizards to spend more time under the shrubs to stay cool and spend less time foraging,” said Alessandro Filazzola, a graduate biology student at York University in Toronto and lead author of the study published in Basic and Applied Ecology. “If this continues, we might lose this species altogether. It could be an alarm bell.”

From 2013 to 2014, Filazzola and his collaborators investigated the relationship between the lizards and the shrubs’ locations and traits in the Panoche Hills. They geotagged 700 shrubs, measured their physical characteristics and collected samples.

For two weeks each year, they spent early mornings surveying this landscape for the reptiles by enlisting detection dogs from Working Dogs for Conservation, an organization that trains rescue dogs for environmental projects, to sniff out lizard droppings.

“Spending all day in the desert, I might see one lizard, but with these dogs and in less time, we could find six or seven scats, so we’d be able to measure a lot of lizards,” Filazzola said. “It’s fun working with dogs.”

Before this, Filazzola said, sniffer dogs had only been used to locate actual animals or larger scat.

Given the association between the lizards and shrubs, the recent expansion of solar farms in the region could represent a threat to the species by supplanting the vegetation, Filazzola said. The lizards already had lost much of their habitat to expanding agricultural operations, he said.

“Think about the shrub as this focal point that many other species rely on,” Filazzola said. ”Removing it without considering the consequences could be a big deal. There are some solar farms leading the charge by doing things differently to help preserve native species because findings show you can’t just turn habitat into a concrete jungle.”

Invasive grasses also pose a problem for the lizard, Filazzola said. Rising to about a foot, they impede the ability of the reptile to move, catch prey and escape predators because it is adapted to scurry across desert sand. The nonnative plants also inhibit the arid shrubs from reproducing, which could eventually turn the landscape shrubless, he said.

To identify long-term trends, Filazzola and his partners have continued to examine the shrubs and lizards at Panoche Hills every year since their initial study. He is also working with a team using radio tags to gather more information on the lizards’ positions and how often and long they are there to try to shed more light on the specific nature of the interaction between the animal and the plant.

“I hope that it’s going to be the beginning of a lot of other projects that build on this association and help make better management decisions,” he said.

Header Image: Managing arid shrubs could enhance the conservation of the blunt-nosed leopard lizard (Gambelia sila), which currently faces extinction because of habitat disturbance, damage and fragmentation. ©Alan Schmierer