Share this article

Over more than a century, seabirds have changed prey

Seabirds in Hawaii have changed their prey preference over the last 125 years, according to new research, suggesting that more birds are consuming squid rather than fish.

This shift to eating species that are lower on the food chain can provide more information about the ocean ecosystem, researchers said. Instead of using drones or water samples to study the waters, researchers are using museum specimens to gather a historical record of what is being eaten.

“Birds can live for quite a while, and as they operate throughout their environment, they can make decisions about prey items they’re going to eat,” said Tyler Gagne, an assistant research scientist at Monterey Bay Aquarium and lead author of the recent study published Science Advances.

Unlike drones or water buoys that can collect satellite data, Gagne said, using information collected from museum bird specimens allowed him to go back in history to determine what seabirds were consuming over time.

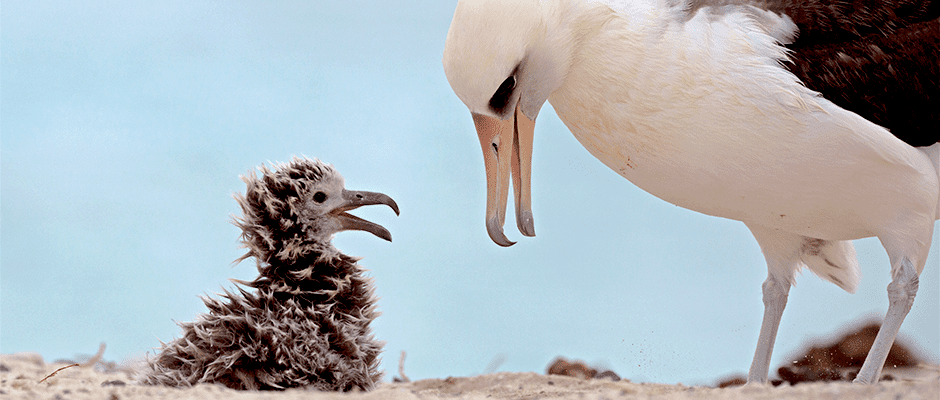

In the study, the research team collected data from specimens of North Pacific seabird species from the Bishop Museum in Hawaii: the Laysan’s albatross (Phoebastria immutabilis), Bulwer’s petrel (Bulweria bulwerii), wedge-tailed shearwater (Puffinus pacificus), white-tailed tropicbird (Phaethon lepturus), brown booby (Sula leucogaster), brown noddy (Anous stolidus), white tern (Gygis alba), and sooty tern (Onychoprion fuscatus).

The specimens dated from 1898 to 2016. Using their feathers, they conducted compound specific stable isotope analysis to figure out what the birds consumed.

They found the seabirds are consistently eating lower on the food web than they did historically, appearing to consume more squid as their dominant prey.

“This suggests that the food webs are not as complex as they were historically,” Gagne said.

This switch could be troublesome for the birds, he said, because squid numbers can be volatile and respond strongly to climate fluctuation. “It’s not a particularly reliable food source,” he said.

A few drivers may be responsible for this change, Gagne said. Some birds, like brown boobies, don’t fly as efficiently, so the prey they choose must be in closer proximity. When their traditional prey is not available, due to climate changes or other factors, he said, their diet can change dramatically.

Gagne suggests using seabirds as an indicator species for the ocean environment. Past data on prey sources were collected from fisheries, but they can be biased, Gagne said, since fisheries are driven by economics and market forces. Seabirds, on the other hand, act as a sort of “canary in a coal mine” to signal changes in ocean health, Gagne said.

They “are an excellent indicator species,” he said. “And this way, you can more efficiently, with less bias, monitor ecosystem health and make broader decisions based on that.”

Header Image: A Laysan and its chick spends time on Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument in Hawaii. ©Dan Clark/USFWS