Share this article

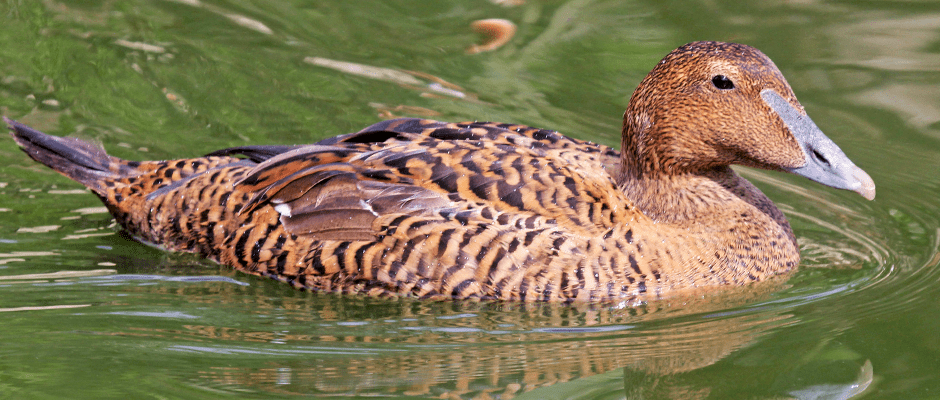

JWM study: New England eiders return to same near-shore wintering areas

In southern New England, eiders winter at the same sites every year, choosing habitats with shallow water and hard bottoms close to the shore, a recent study from Rhode Island demonstrates.

“They’re very site-faithful to those areas each winter,” said Joshua Beuth, wildlife biologist for the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management’s Division of Fish and Wildlife and first author on the paper published in the June issue of the Journal of Wildlife Management.

In recent years, these northern sea ducks have been declining in Maine and southeastern Canada at the southern edge of their breeding range and face various pressures elsewhere, Beuth said. Figuring out where they winter could help minimize human disturbances to vital eider habitat and protect their populations.

The Atlantic Coast is seeing a rise in both offshore wind and aquaculture farms. “If they’re put in areas important to sea ducks, it could cause habitat loss,” he said, possibly resulting in displacement, longer flight times and greater energy expenditures for eiders.

“Birds coming to an area are likely to return, so anything put there will repeatedly disturb them,” Beuth said.

From December 2011 to July 2013, Beuth and fellow biologists at the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management and University of Rhode Island tracked migrating common eiders (Somateria mollissima). The researchers fixed 26 adult females with satellite transmitters on wintering grounds in Rhode Island and looked at the habitat the sea ducks selected each winter.

“Eighty percent of birds returned to the study area the following winter,” Beuth said. “Most returned to their own individual areas from the prior winter.”

These tended to be places close to the coast, he said, where the seafloor was hard, the water was no more than 60 feet deep — shallow enough for them to dive — and blue mussels, their main prey, occurred.

Pinpointing eider habitat helps managers understand the consequences of offshore industries for the animals and their foraging on the landscape and to mitigate these effects by recommending that these activities be placed in less important habitat.

Researchers at the University of Rhode Island and Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management are now performing a similar habitat use and movement analysis using satellite transmitters in white-winged scoters (Melanitta deglandi) and long-tailed ducks (Clangula hyemalis).

Header Image: ©Dick Daniels