Share this article

JWM: Fishermen alter dingo foraging behavior

When Eloïse Déaux spent time on a beach on Australia’s Fraser Island, she noticed that dingoes (Canis dingo) behaved differently when fishermen were around.

“When fishermen were standing there and fishing, dingoes would just be lying around or walking around them a little bit, seemingly waiting for something to happen,” said Déaux, then a PhD student with Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia and lead author of a recent study on the species published in the Journal of Wildlife Management.

While she was conducting an acoustic monitoring project on dingoes, she decided to pursue a side project looking at this behavior.

Whenever she spotted a dingo on the beach, Déaux stopped to collect all the data she could on the individual, including if it had a marker that identified it, how many other dingoes were in the vicinity and how many people were in the area. If she had time, she would stop and videotape the animal for as long as she could.

“It was lucky for me because you do spot dingoes a lot when you’re on the island and on that particular beach,” she said.

Then, Déaux divided her data between dingoes that were around people that had potential food sources, such as when they were having breakfast on the beach or fishing, and those that weren’t. Then, she watched the videos of dingoes and compared the behavior of the two groups.

Déaux found that when the dingoes were not around people, they completed normal foraging behavior, walking alongside the beach sniffing around for food. “They move in a zigzagging manner,” she said. “This is the solitary foraging technique for a dingo in this situation.”

However, when the dingoes were around people (and it the case of the study it was mostly fishermen), they spent most of their time still either resting or alert. They seemed to be waiting and watching the people around them.

Déaux said if dingoes habituate to people, it can become dangerous. “Every year, there are a number of cases of people being harassed by dingoes, and there even has been a death on the island,” she said. “This can be a threat to tourists on the island.”

Déaux said one of the main reasons tourists come to the island is to fish. But dingoes are quick learners and can steal their fish. Or they might wait until the fisherman finishes and then consume the fish guts left over.

Currently, measures in place try to manage human-dingo conflict. Fishermen are provided with cleaning stations, are not supposed to clean their fish in front of dingoes and must bury any parts left over. But “dingoes are not stupid,” Déaux said. “They’re going to smell it and dig it out.”

She suggests implementing time restrictions during critical periods when dingoes are out hunting or possibly restricting certain fishing areas where dingoes are often present. She also encouraged further research to see if dingoes get more food from sticking around fishermen.

“It’s an area that’s really important from a management perspective,” she said. “How much of an influence are dynamics between fishermen and dingoes?”

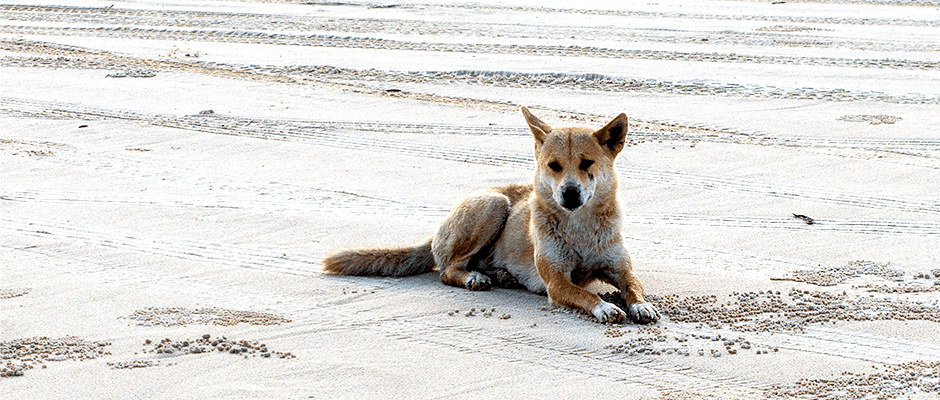

Header Image: A dingo lies on a beach on Fraser Island. ©David Gardiner