With humans increasingly encroaching on wildlife habitat, it makes sense that some animals would be disturbed by their presence.

However, over time, many species are growing accustomed to these encounters and are becoming more tolerant of humans. In a study recently published in Nature Communications, researchers from Brazil, New Zealand and the University of California Los Angeles examined characteristics of animals that help determine the extent to which they tolerate human presence.

The research team led by Daniel Blumstein, a professor and chair of ecology and evolutionary biology at UCLA and senior author of the study, completed a meta-analysis of more than 75 studies on birds, mammals and lizards that examined species tolerance to human disturbance. The studies used a measure of flight initiation distance — how close you can get to an animal before it flies, runs or scampers away, Blumstein said.

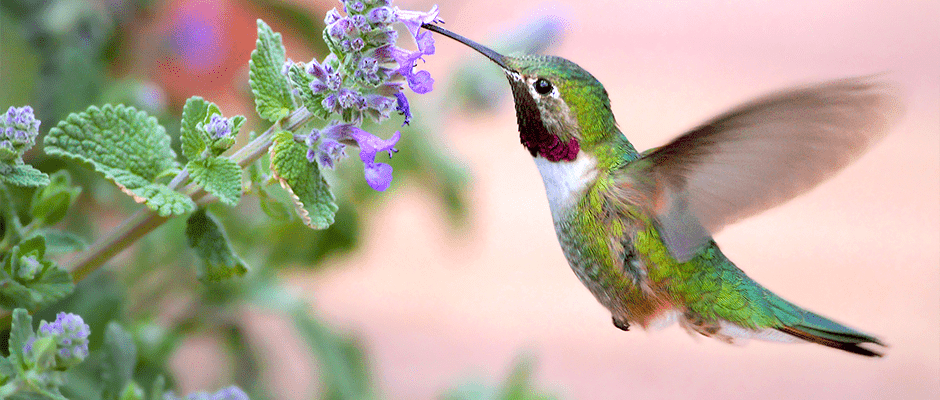

The team found that birds, which made up the majority of the studies in the meta-analysis, in more heavily populated urban areas are more tolerant than birds in rural areas in that they tolerated closer approaches from humans. Further, larger birds such as pelicans (genus Pelecanus) and black-backed gulls (Larus marinus) were more tolerant of humans than smaller birds such as hummingbirds (Trochilidae). “We found that big species were more tolerant of humans because they were probably more easily disturbed in the first place,” said Blumstein. This contradicts previous notions that large birds are more intolerant of humans and suggests that we should focus more on smaller species’ tolerance of people, he said.

Enter Ecotourism

The study also suggests that ecotourism — a rapidly growing industry — might be less harmful to larger birds than previously thought since they are more likely to tolerate human encounters, Blumstein said.

That adaptability does have a downside, however. In a related study recently published in Trends in Ecology and Evolution, Blumstein and colleagues from Brazilan universities examined whether ecotourism increases an animal’s vulnerability to predators and found that nature-based tourism can put some animals at risk.

“There are 8 billion visitors a year to terrestrial protected areas around the world,” Blumstein said, noting that eventually animals tend to habituate to the visitors. “Some circumstances may lead to them becoming more relaxed or blasé which can increase their availability to predators.”

Blumstein hopes that both of these studies will help predict how and when animals will likely adapt to human presence, which in turn could inform survival and reproductive success, he said. “We can develop plausible scenarios whereby species become more tolerant to humans,” he said. “The goal is to understand when these are beneficial for the animals themselves.”

Article by Dana Kobilinsky