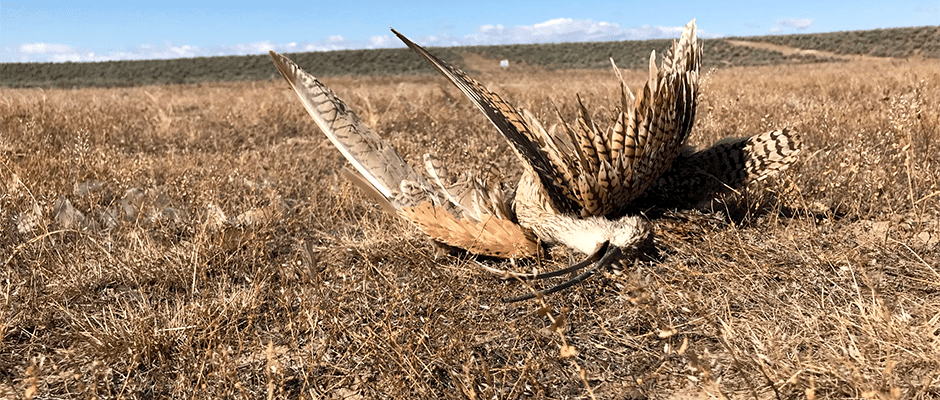

On his first day studying long-billed curlews (Numenius americanus) in southwest Idaho, Jay Carlisle came across a disturbing find. A curlew lay dead on the side of the road, shot through the head. Nine years later, that sight proved to be an omen.

“It took me years to realize the gravity of the situation,” said Carlisle, researcher director at the Intermountain Bird Observatory and associate research professor at Boise State University.

Long-billed curlews had been studied in the region in the late 1970s by a University of Montana team — a time when their population density was among the highest throughout the bird’s range. In collaboration with the Idaho Department of Fish and Game and the Bureau of Land Management, Carlisle returned an area now known as the Long-billed Curlew Habitat Area of Critical Environmental Concern in April 2009 to try to understand the decline. Maybe it was tied to changes in their habitat, he thought. Nonnative grasses and forbs were moving in. Ranchers were shifting from sheep to cattle. Could that have something to do with it?

After a few years of research focused on the breeding season — during which they found lower reproductive success than historical rates, a declining population and a few more shot curlews — he and his Boise State team outfitted birds with satellite transmitters. They wanted to get “the lay of the land,” Carlisle said —a sense of how the birds behave throughout the year, from their springtime brooding in the Intermountain West to their wintering grounds in California and Mexico.

But the transmitters ended up revealing an unexpected chief threat to the birds: poachers. Of the 16 adult birds with fitted with transmitters on BLM lands, seven of them — about 44 percent — turned up illegally shot dead since 2013. The latest was on June 1, 2018 at the Morley Nelson Snake River Birds of Prey National Conservation Area, southwest of Boise.

“It took me a few years for it to really dawn on me that this is the main factor here,” Carlisle said. “Now it’s become clear, to myself and others, that this is a very unsustainable level of illegal shooting. This is the number one reason for the decline of the bird in this region. It was definitely shocking.” Even if the proportion of shot birds isn’t something they can extrapolate to the whole population, Carlisle said, “I think it’s an indicator that something really serious is happening.”

Now, wildlife managers are struggling to figure out what to do about it. Many of the curlews in the region — and most of the illegal shooting incidents — occur on Bureau of Land Management land, including the national conservation area and the Long-Billed Curlew Habitat Area of Critical Environmental Concern.

Carlisle’s team hasn’t uncovered poaching in other areas where they’re studying the birds, including Montana, Wyoming and elsewhere in Idaho. Of the 56 birds with transmitters in those areas, none has been shot. So why is poaching such a severe problem in southwest Idaho — on lands particularly designated for bird conservation?

“It’s really hard to speculate on that,” said Amanda Hoffman, manager at the Morley Nelson conservation area. “This is such a new issue to us that we don’t really have an understanding of what’s driving that. Certainly, that area is heavily used for recreational shooting.”

Unlike the other areas they studied, Carlisle said, the southwest Idaho locations have high populations of ground-squirrels and prairie dogs, which are popular targets for legal target shooting. And while it seems to be an emerging issue on the NCA, it may not be new to the region, he said. In the 1970s study, researchers found nine birds that appeared to be shot on the ACEC.

To try to combat the problem, the BLM and Intermountain Bird Observatory are participating in hunter

education classes to discourage the shooting of curlews and raptors. The observatory hosts programs in schools — Curlews in the Classroom — to teach about the birds and encourage students and parents to respect them. Managers have also been working with local and national media to highlight the issue.

This past year, the Intermountain Bird Observatory, BLM and other partners, including the Army National Guard and Underground Guns, also tried setting up information tents in areas where they hoped to find recreational shooters. It’s a difficult group to reach, Hoffman said. “They’re not like other user groups where there’s an organized and structured organization we can go to.”

Tighter enforcement may also help, Carlisle said, but it’s difficult. “There’s just so much law enforcement to go around,” he said, “and there are lots of law enforcement issues that need to be addressed. The likelihood of a law enforcement officer being present during the two seconds it takes to pull a trigger is pretty low. It’s easy for folks to get away with this.”

Because the curlews are migratory, they’re protected under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, which allows up to a $15,000 fine and six months in prison for knowingly taking a bird without a permit. That should be a discouragement, Hoffman said, but the public knows so little about curlews, they may not know they’re migratory and protected, and that shooting them is a federal offense.

“You wonder why this is happening,” Carlisle said. “Is it malicious? Is it just ignorance? I think it’s more the latter than the former.”

The Bureau of Land Management is a Premier Partner of The Wildlife Society.

Article by David Frey