Share this article

Reptile atlas highlights more biodiversity hotspots

Compared to other vertebrates, reptiles have been a mystery to science, and their distribution has been less understood than that of mammals, birds and amphibians. A recently completed global atlas of terrestrial vertebrates is changing that, though, by adding new data about where the world’s reptiles are found and shedding light on the need to conserve the often-neglected dry regions many reptiles inhabit.

“We hope our paper will raise awareness of reptiles deserving preservation and make people know the data exists,” said Shai Meiri, corresponding author on the study published in Nature Ecology & Evolution. “It can help refocus on-the-ground regional or country-level conservation planning.”

Meiri, a professor at Tel Aviv University, Israel, was on an international team of researchers aiming to map reptiles as others had done with mammals, birds and amphibians to round out the geographic puzzle of the 31,000 vertebrate species on land. His team collated information going back 200 years from papers, reports, databases, field guides and herpetology books featuring over 10,000 reptile species around the world and consulted reptile experts working in areas published sources didn’t cover. For their comprehensive analysis, the scientists also pulled maps from up to a decade ago on about 10,000 birds from BirdLife International and on about 5,000 mammals and 6,000 amphibians from the International Union for the Conservation of Nature.

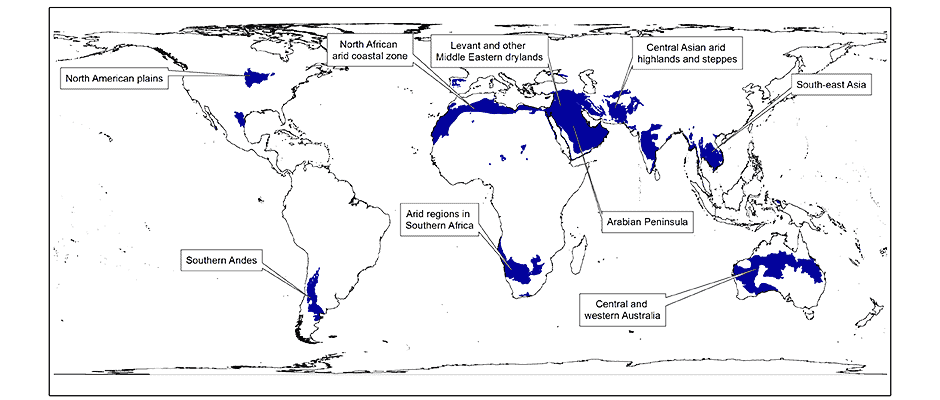

The biologists then produced a series of maps illustrating species richness for lizards, snakes, turtles and tortoises and for all reptiles put together. The maps showed that although snakes tended to occur where mammals, birds and amphibians did, lizards and turtles exhibited distinct geographic patterns.

“The southern U.S. is a hotspot for turtles and is important for reptile conservation,” Meiri said.

He and his colleagues also mapped the proportion of reptiles to all terrestrial vertebrates. They found that the number of reptiles that lived in the southeastern United States, Australia and a vast arid expanse stretching from the Sahara to northwestern India was higher than expected by the sum of mammals, birds and amphibians in those places.

The team’s final map highlighted conservation priorities for land vertebrates across the planet, including the Arabian Peninsula and the Levant, inland southern Africa, the Asian steppes, central Australia and the high southern Andes. In Brazil, where conservationists have been most concerned about the Amazon and Atlantic Forest, Meiri said, the findings have stimulated more interest in the drier northeastern Caatinga, which is rich in reptiles.

“Reptiles shift the focus more toward arid and semiarid regions and islands,” he said.

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature is using maps from the study for its assessments, Meiri said, which so far include only half of the total number of reptile species. He and his partners also plan to model the threats reptiles face globally to fill in more gaps in what they know about these animals.

“If someone did want to conserve reptiles on the ground in particular places, they can write us and we will send them the data,” he said.

Header Image: Mapping reptile species around the world brings new geographic conservation priorities to light. ©Uri Roll