Share this article

Numbers matter in bighorn sheep translocation

Smaller translocations of bighorn sheep may be less successful than larger translocations.

According to new research that analyzed the genetic makeup of different populations of bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis) — some that have benefited from translocations and some that haven’t — the impact of the management actions depends on the number of animals moved.

“These smaller translocations may have been less successful,” said Elizabeth Flesch, a postdoctoral researcher at Montana State University and the lead author of a study published recently in Ecology and Evolution.

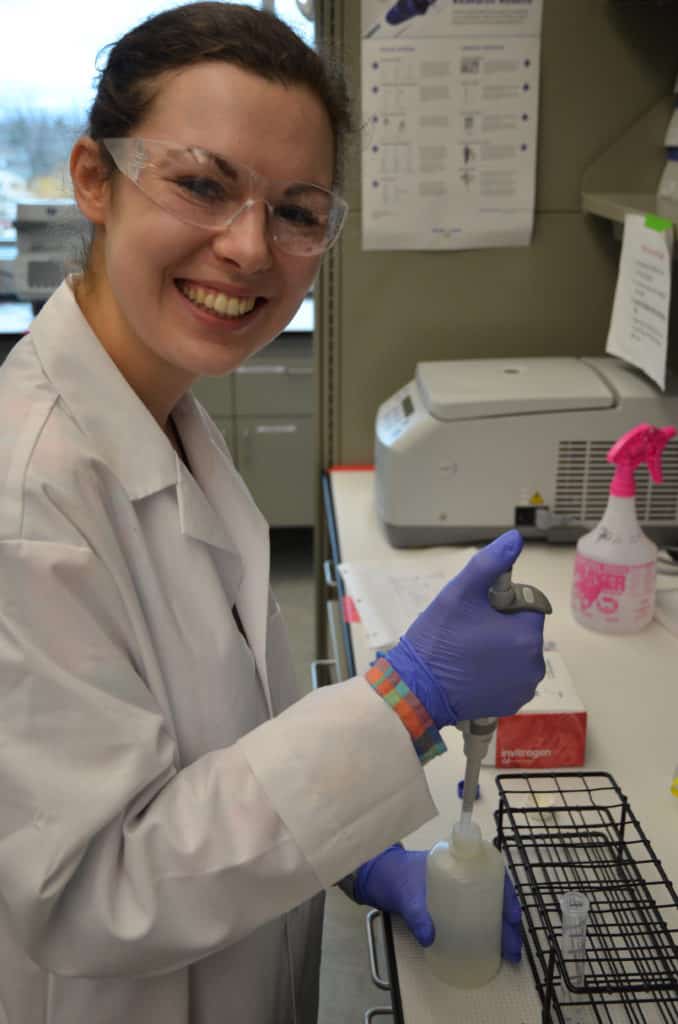

Elizabeth Flesch works with a bighorn sheep DNA sample in the lab.

Credit: Phil Merta of Montana State University

The ungulates used to be more widely distributed across the U.S. Rocky Mountains. But with European colonization came hunting and domestic sheep that not only competed with the bighorns but spread new diseases, causing the bighorns to decline.

Managers have been working since the 1920s to translocate healthy animals from abundant populations to areas where they had disappeared in parts of the U.S. and Canada.

But researchers haven’t always followed up on the success of these management measures. So Flesch and her colleagues stepped in to take a look at the genetic makeup of different bighorn populations as a way of informing more successful translocations in the future.

They collected 20 to 25 DNA samples from 14 different populations, working with agencies in different western states to obtain the blood and tissue samples.

They were able to identify the genetic signatures of native herds, and reintroduced herds showed genetic signatures similar to their origin populations.

Flesch, at the time a PhD student, and her colleagues also found that the translocations seemed to be effective at establishing new populations where managers had placed animals in areas that hadn’t had any for some time.

But other smaller-scale translocations, sometimes undertaken to supplement small native populations with fresh DNA, weren’t always as successful in infusing new genes, Flesch said.

Genetic analysis of bighorn sheep showed that moving larger numbers of animals has a bigger effect on gene pools of populations. Credit: Elizabeth Flesch

Translocation efforts can vary regarding the numbers of males or females moved. When just a few rams were introduced, Flesch said their analysis showed it didn’t have much of an effect on introducing new genes to a herd. This may be due to the wandering nature of rams during the breeding season, or just because the introduced males didn’t manage to outcompete local rams in terms of mating.

Flesch and her co-authors said the results of their research can give “guidance to enhance genetic contribution of augmentations and reintroductions to aid in bighorn sheep restoration.”

Header Image:

Bighorn sheep have often been translocated to reestablish populations or supplement smaller herds.

Credit: Elizabeth Flesch