In the first-known study to examine the long-term effects of tree removal in northwestern Colorado on bird habitat, researchers found fundamental changes in the bird community. The findings suggest that land managers may need to reconsider current tree reduction efforts that have been used for decades.

“The surprising thing was there were a lot of birds both in the clearings and in the forests; [but] we saw a complete shift in the bird communities,” said Travis Gallo, lead author of the study published in The Journal of Wildlife Management. He conducted the study as part of his thesis research in wildlife conservation at Colorado State’s Department of Fish, Wildlife and Conservation Biology. “These cleared areas may actually be changing the whole ecosystem to more of a shrub-brush ecosystem from a forest ecosystem.”

For decades, private landowners have removed trees on a large-scale basis in certain areas with the intention of improving forage for livestock and wildlife. Gallo says the new study suggests that the previous removal of pinyon (Pinus edulis) and juniper (Juniperus osteosperma) trees benefited or had no effect on the populations of certain bird species, but came at a cost to others — even decades later. For the study, trained observers conducted point-counts in 25 previously disturbed areas and 25 undisturbed areas.

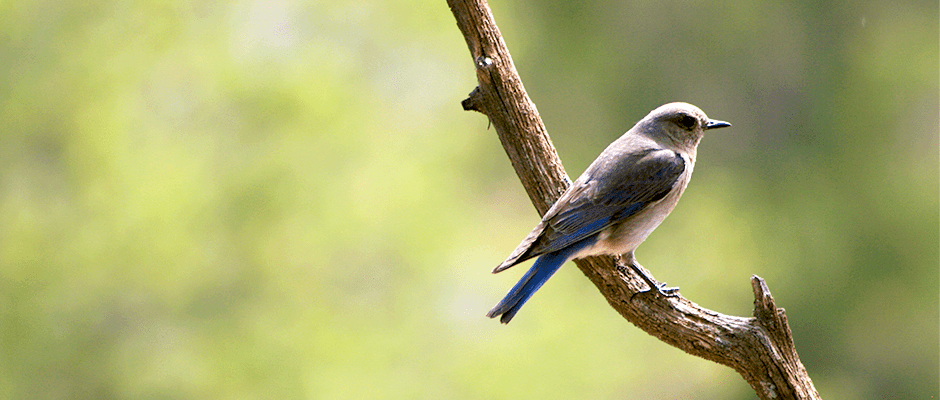

The areas where trees had been removed by a process called “chaining” — basically dragging a chain between two bulldozers — showed fewer species, and were dominated by shrubland-obligate birds. Out of 21 species, five species showed neither positive nor negative results. Five sagebrush species, such as mountain bluebird (Sialia currucoides), were more prevalent. However, there was a decline in 11 woodland bird species, including juniper titmouse (Baeolophus ridgwayi), and cavity-nesting birds that prefer or need larger trees for cover. Even after several decades, not enough time had elapsed to allow the woodland bird populations to recuperate.

“We expected after 40 years the bird community would’ve balanced out, but what we actually found was a whole different type of bird community using the sites,” Gallo said.

“It’s really interesting because it’s very arid out in the western United States, so the system is very slow-growing. It’s not like you cut down a tree and the tree grows back very quickly. It takes a really long time to go back to a forested ecosystem.”

The findings suggest that the long-term impacts of management decisions may have unexpected consequences.

“We really need to manage landscapes for the well-being of all wildlife and not just ones we hunt or a single species we care about,” Gallo said, “A lot of management is done with the best of intentions to create habitat for a certain species, but our study shows we may not see the long-term consequences to everything else.”

Tara DeSantis, MS, is a nature enthusiast, writer, and photographer.

Article by The Wildlife Society